Issues so far

- Indians have been made to believe high population is good

- But the constantly growing number adds to the country\'s problems

Solutions

- Some issues about demographic theories need to be understood

- There are enough inherent issues that need fixing before population can be tackled

More in the story

- The demographic theories

- Potential solutions to the population issue

Ever since Sanjay Gandhi's horrific nasbandi programme and its electoral consequences, politicians of all hues have steered away from ever talking about population problems and fertility control measures.

The bureaucracy and tame sarkari economists, who are all very quick at picking up cues from their political masters, have cleverly flipped the whole issue on its head.

They have popularised the phrase 'demographic dividend', implying in a rather disingenuous fashion, that our huge and growing population is in some sense an economic blessing - a dividend rather than a problem.

To top it all, in recent times loonies of various hues have actively exhorted followers and congregations to have more children; the strength of vote banks lies in their numbers and hence the encouragement to 'go forth and multiply'.In this context, it is useful to go back to the basics of demographic theory and the actual patterns of demographic behaviour in India to understand where the truth lies.

Uncovering the truth

The experience of the developed West, and later of the developing Rest, has led to the formulation of a 'theory' of demographic transition.

In summary, from around the 18th century, societies, starting with those in north western Europe, began transitioning from populations characterised by high birth rates and high death rates to those with low death rates and low birth rates.

The transition was a long and slow one for the first movers and led to major, far-reaching changes, not just in the size and structure of populations, but also in social mores, economic development and 'societal complexity' in general.

The transition starts with a decline in mortality - a fall in death rates - and results in an increase in population since birth rates continue to be high for a while.

Over time, however, as death rates drop, life expectancy and average family size increase, rapid urbanisation happens and socio-economic pressures build up, and that eventually result in a drop in fertility.

Birth rates fall and, once they come down to the level of death rates, populations stabilise at a higher level than before the transition.

The population structures too, change dramatically - from a small, youthful, largely rural and short-lived population we get a larger, much older on average, urban and long-lived population.

The socio-economic-cultural context determines the details of how the transition works out - the speed with which death rates fall, the time it takes for the fertility rates to drop, and the pattern of social transformation and economic development that accompany the transition.

Changing patterns

The basic point is that once sustained mortality decline happens, the rest follow. In the course of the transition, as the population grows and before it ages significantly, there is a period when a high proportion of the population is in the working age group, 15-65 years.

This 'window' is sometimes referred to as the time of the demographic dividend. When a high proportion of the population is in the productive age group, it is logical to assert that potentially it is a great time to ramp up economic activity - the ideal time for economic growth and perhaps even development.

The important point, however, is that it is only a potential and a very sharp double-edged sword of potential at that.

A look at the basic Indian demographic experience is necessary at this stage:

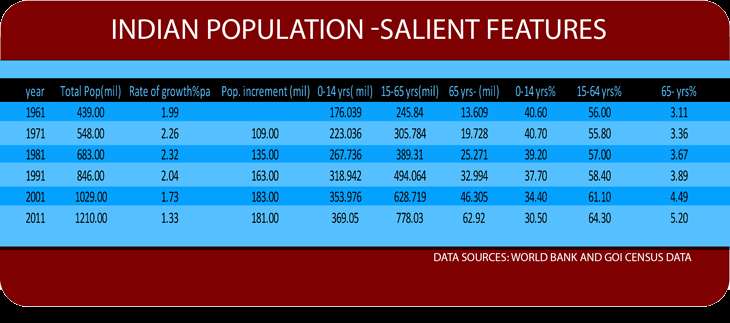

We crossed the billion mark sometime between 1991 and 2001 and added more than 180 million people every decade after 1991.

This has happened despite the fact that the birth rate has begun dropping significantly after 1981.

In thirty years, from 1981 to 2011, our population has almost doubled - from 683 million to 1210 million.

The proportion of population below 15 years is declining, that in the 15-65 years increasing, as is population aged above 65 years.

We are well into the transition, it appears, and fertility decline is marked - the rate of growth of population has dropped significantly.

The problems

The problem, however, is the absolute size of our population and the fact that even a relatively low growth rate still means a very large increment in absolute numbers.

In addition to a huge and still increasing population, we have a crippling shortage of resources.

We don't need data to demonstrate this - we simply have to look around us and that too in the most important cities of India.

There was a time I remember, one drank water out of the tap in New Delhi - water filters were not required. Today, water purifiers are a growth industry, as is bottled drinking water.

Garbage disposal in the NCR is a ghastly process, open drains grid the Noida landscape and during the dengue season private hospitals put rows of beds in corridors - with a chair and a table fan beside each bed - to cater to the jump in business.

Getting admission to a 'good' school is nightmarish unless you have huge amounts of money to 'donate' and it is difficult even then. Top class public health facilities do exist in Delhi but have you ever tried to get to a doctor in AIIMS?

Elsewhere, government hospitals are terrible, even in large towns of relatively prosperous and better-governed states, and private health services are hugely expensive and blatantly extractive.

How it stands today

We thus have a situation of a burgeoning young population, the vast majority of which is poorly educated and unskilled.

We have grossly inadequate resources even for the provision of clean drinking water, good basic education and minimal medical facilities.

We have slow growing agriculture, capital and skill-intensive manufacturing and services sectors and marked inequality in income and wealth.

We have urbanisation that creates a festering slum across the road from every middle and upper middle-class development with landscaped gardens and clubhouse, and still the rural folks come flooding in - a clear indicator of just how things are back in the village!

We have almost 800 million people in the working age group, with more coming; little hopes of gainful and productive employment and stark inequality in income and wealth staring those under and unemployed in the face.

No wonder that even 'dominant' agricultural castes are asking for reservation in government jobs!

Are there solutions?

Population for India today is a problem not a dividend of any sort, and problems have to be dealt with, not hidden by clever relabeling and slick distortions of economic 'theory'.

Fertility control measures at this stage when fertility is low and falling are unlikely to help very much.

The problem is with us - full-blown - and we are back to formulating and implementing basic development policy to handle a set of rather difficult socio-economic circumstances.

Development economists of various ideological persuasions have over the years elaborated detailed prescriptions for bringing about growth with social justice**.

The fundamental problem that persists, however, is that the Indian leadership class has never summoned up the will to disregard short-term political compulsions and entrenched vested interests and actually push through those policies that are advocated by their ideological friends and fellow travellers.

The Katha-Upanishad's observation is brilliantly apt in our context -

'The good is one thing, the pleasant another; these two having different objects, chain a man. It is well with him who clings to the good; he who chooses the pleasant misses his end..........The wise prefers the good to the pleasant, but the fool chooses the pleasant through greed and avarice.' ***

We have missed the goal of equitable growth and social justice for over sixty years now but we continue to wait for Godot.

* Tim Dyson : Population and Development-The demographic transition

** Dreze and Sen: An uncertain Glory-India and its contradictions

Bhagwati and Panagariya: India's Tryst with destiny

***The Katha Upanishad Translated by Max Muller

Edited by Jhinuk Sen

Also Read: Modern slave trade: how to count a 'hidden' population of 46 million

Also Read: Population Explosion: India expected to become world's most populous country by 2050

Also Read: #Census2011: Muslim population growing faster than Hindus; Twitter jokes follow

First published: 11 July 2016, 3:59 IST

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)