What you need to know

- Asaduddin Owaisi heads a right-wing Muslim party, the Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen, that\'s making rapid gains in Indian politics.

- MIM wants to dislodge \'secular\' parties like the Congress and become the sole representative of India\'s Muslims.

What\'s the gameplan

- The party wins Muslim votes by stoking fears that Islam is in danger (Islam khatre mein hai).

- Its primary target is the young, semi-skilled and unorganised. It marries their economic anxieties with identity politics.

What\'s the impact

- In the 2014 Maharashtra Assembly elections, it won two seats, Aurangabad Central and Byculla, both Muslim majority areas.

- Most recently, it swept the local elections again in Aurangabad.

Why it matters

- MIM\'s brand of politics will isolate Muslims further from other communities.

- By playing on their fears, it will Muslims away from real concerns like jobs and poverty.

- By mirroring the rhetoric of the Hindu right-wing, it will help the Sangh Parivar create communal tensions.

- In the long run, MIM\'s rise will weaken Indian secularism.

A new star is rising on the map of Muslim politics in India-or at least Maharashtra. The MIM.

First, it stormed the city of Nanded in 2012 by winning 11 seats in the municipal corporation there. Then the MIM made news by winning two seats in the Maharashtra Assembly.

Most recently, it performed impressively in Aurangabad city's local election. It also has a sizeable presence in the newly formed Telangana state's Assembly.

MIM strategy: playing on anxiety

MIM, and particularly its leadership, speaks a language that is radical, bordering on the provocative. In places where the Muslim community has a sizeable presence, this language gives the Muslims a sense of confidence and strength.

The youth-mostly belonging to the category of semi-skilled and less organised occupations-are the main targets of the MIM's evocative propaganda. Very adroitly, MIM achieves three things.

One, it situates itself as the main spokespersons of 'Muslim' interests, replacing the local clergy and orthodox elements.

Two, it speaks the language of Muslim marginalisation that easily convinces Muslims from economically weaker and unstable sections.

And three, by raising fears about an impending 'Hindu onslaught', the MIM rhetoric simultaneously creates an atmosphere of imminent danger to Islam (Islam khatre mein hai).

In other words, MIM builds on the orthodox constituency within the community and also appeals to the material anxieties of Muslims. It then relates those anxieties to the community's religious persuasion.

Thus, the material aspect of the suffering is lost and the identity aspect becomes primary, both in its own polemic and the perception of its followers.

Hence the MIM's appeal spans cross-sections of the Muslim community-and effectively pushes the community away from secular concerns and politics, while speaking in the name and language of secularism.

Is there anything called a consolidated 'Muslim' vote?

So what does MIM's increasing electoral success in Muslim-concentrated localities indicate?

First, it would adversely impact the Congress. The 2014 parliamentary elections have left the Congress only its Muslim votes and some share of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes vote in some states. If the Muslim vote deserts the party, the end of the Congress would be further hastened.

MIM has long been active in the city of Hyderabad and its nearby areas. Its spread to the Marathwada region of Maharashtra was to be expected, as the regions are geographically contiguous and have a large Muslim population.

While today the Congress seems much more dependent on Muslim votes than ever before, it is not as if Muslims across the country vote 'en bloc' in favour of the Congress-or any one party.

MIM wants to become the party for every Indian Muslim. It could end up becoming the Hindutva brigade's biggest ally

Post-emergency, Muslims voted the Janata Party in large proportion. In the 90s, Lalu Yadav and Mulayam Singh, wrested a large share of Muslim votes from the Congress in Bihar and UP respectively.

In West Bengal, the Left till recently, had the confidence of the Muslims. But these parties did not claim to either chiefly or exclusively represent Muslims.

On the other hand, there are instances of Muslims relying on their independent political vehicle.

In Kerala, the Muslim community has a local version of the Muslim League which they support very often. At the other end of the country, in Kashmir, National Conference, and more recently, the PDP have control over Muslim votes.

Since 2009, the All India United Democratic Front (AIUDF) has made waves in Assam by garnering the Muslim vote there.

MIM is part of this trend-a search for an independent political vehicle for the Muslim community.

Why Muslims may not benefit from a Muslim party

Active since late 1950s, the MIM claims to cater to the interests of 'Muslims, Dalits, BCs and minorities'; alludes to the violence and looting that targeted Muslims 'during the police action of Hyderabad'; declares its commitment to 'true faith', the Indian Constitution, and vows for secularism.

Parties likes the MIM present a dilemma: should one reject such parties because they are based on religion?

If so, what is wrong in a community gaining agency through a political vehicle such as the MIM?

Do we not consider the BSP an important milestone in the trajectory of Dalit politics because it gave Scheduled Castes a sense of pride and political autonomy?

Yet, parties like MIM implicitly suggest that each community must have its own party. If that happens, won't our politics be community-based and hence less than secular?

Why should Muslims feel it necessary to have an independent political vehicle? Two answers seem plausible.

One, because other parties do not adequately protect Muslim interests. The largest party in the Lok Sabha today, the BJP, does not have a single Muslim among its 282 MPs. Overall, the present Lok Sabha has only 22 Muslim members.

It is argued that Muslims always get an unfair deal. Their representation has never been 'proportionate' to their numeric share in the population.

It is also argued that most mainstream parties, though not against Muslims, are not interested in genuinely advancing the community's interests and often treat the community instrumentally as a 'vote bank'.

The second answer is that Muslims, as Muslims, have separate interests and hence a separate party is necessary. This assumes a homogenisation of Muslim-ness and Muslim interests-all over the country.

Such a claim has several political limitations.

Wind breaks for identity politics

As the MIM experiment shows, a Muslim party can make electoral gains in only three scenarios.

1) Muslims have to be in a majority in an area. 2) Muslims have to have enough numbers in a situation where the non-Muslim vote gets divided. 3) Muslims enter into a tactical alliance with some non-Muslim sections in order to win.

If the MIM wins in Hyderabad mainly because of the first scenario, it is currently revelling in its electoral gains in the Marathwada region of Maharashtra because of the latter two situations.

In Aurangabad, for instance, the MIM tactically aligned with sections of the Scheduled Castes and reaped rich dividends. However, such alliances are bound to be contingent rather than durable.

In Maharashtra, since the 80s, ambitious political calculations based on a Dalit-Muslim alliance have been floated from time to time. While this can produce electoral victories in some places, the political demands, social expectations and historical trends of the two communities are quite divergent.

Objectively speaking, in most parts of the country, the situation of the Muslims is more comparable to the OBCs than Dalits. (In fact, many Muslim communities have been included in the list of OBCs by the Mandal Commission).

Imperfect solutions

Parties like the MIM can survive and expand mainly on the plank that 'all Muslims have a common interest as Muslims'.

As already argued, this is where the politics of MIM and similar parties becomes problematic.

1) It runs counter to the 'secular' claims such parties make.

2) It presupposes that Muslims across India have a common interest as Muslims.

3) It projects these interests on the basis of identity and religio-cultural parameters rather than material aspirations.

4) It underplays the diversity of intra-community practices, languages and life styles.

5) It discourage spaces for genuine inter-community socio-political interactions (as distinct from tactical calculations).

6) Most crucially, parties like the MIM have a tendency to become the mirror image of their 'Other': the Sangh Parivar.

Their existence and rhetoric, therefore, helps make community based polarisation not only feasible but justifiable. In the process, they intrinsically create political justification and legitimacy for an already ascendant majoritarian politics.

How Muslim parties help the Hindutva agenda

The parties of political Hindutva must secretly be very thankful to MIM.

One, the MIM decimated the Congress in Aurangabad. Two, mutual suspicion, hate and inter-community tension are key ingredients for communal polarisation. The third generation of Owaisis, who are currently leading the MIM, are not exactly known for their moderation. Their politics hinges on fanning communal tensions exactly like the Hindutva brigade. This is a perfect recipe for competitive communalism.

Badruddin Ajmal of the AIUDF achieved almost a similar thing in Assam. One only has to imagine the implications of similar outfits making an intervention in West Bengal or UP or Bihar and how this would benefit those who have desperately been trying to consolidate Hindu voters.

Pyrrhic victories and short-term gains

So, will the politics of MIM help Muslims at all?

For the time being, both in Aurangabad and elsewhere, a diffuse sense of satisfaction and happiness may emerge among Muslims over the pyrrhic victory of the MIM.

Muslim youth who find themselves marginalised both from material well-being and the pursuit of politics may feel a temporary sense of power by joining the MIM.

It will take a while for it to dawn that the 'victory' of the MIM includes the victory of the Shiv Sena in Aurangabad. And that the firebrand rhetoric of the MIM leadership only postpones the real battle for the interests of the poor Muslim.

After all, winning seats in a few cities is a far cry from a robust secular politics, which is different from the emotional blackmailing of Muslims in the name of secularism.

Equally, winning a few seats doesn't reduce the travesty if the word secularism came to be associated with community-based parties and the vitriolic polemics characteristic of the MIM.

The views expressed here are personal and do not reflect those of the organisation.

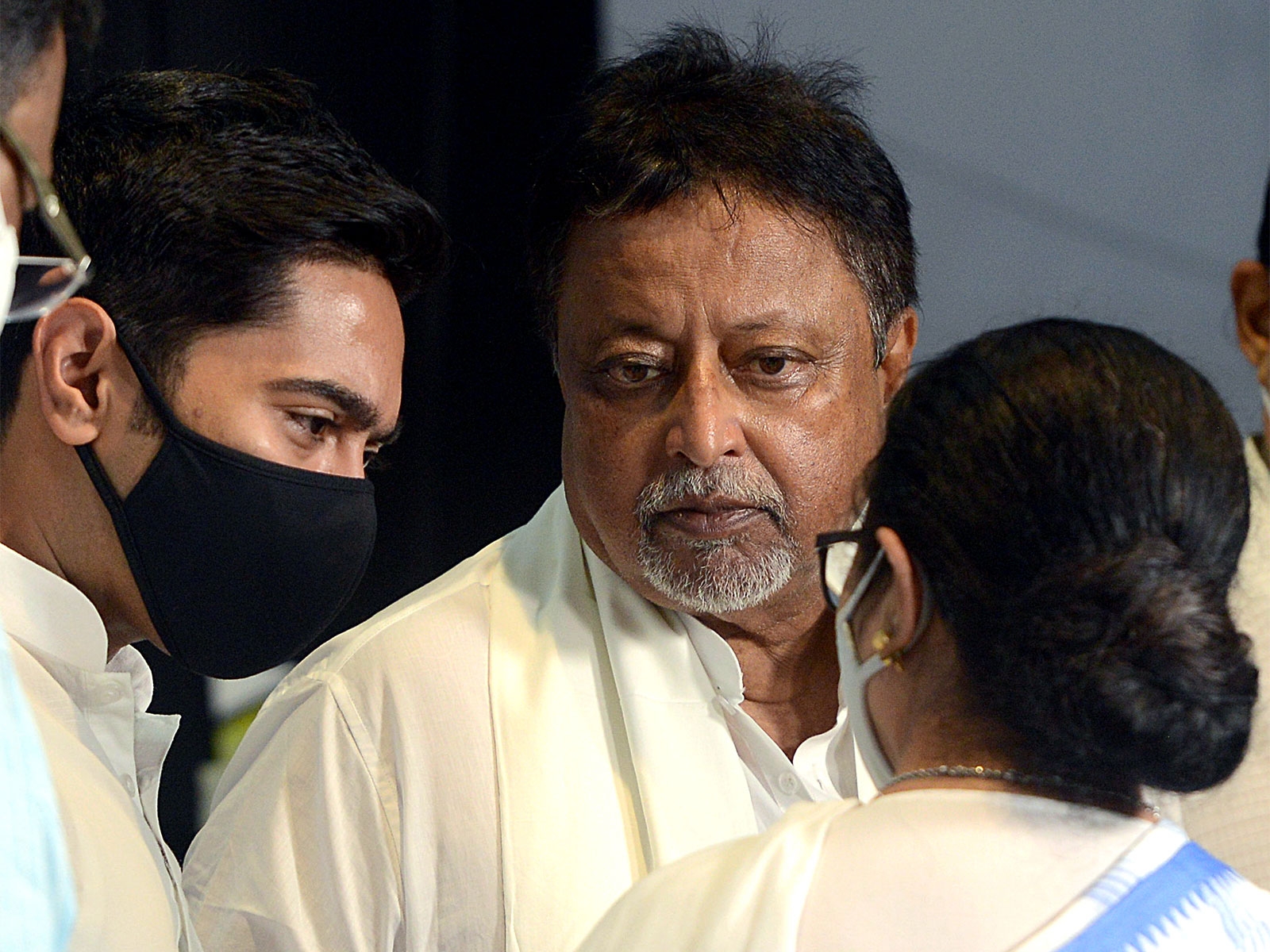

Photo credit: Nongmaithem Vikram Singh/Photo: Noah Seelam/AFP/Getty Images

First published: 24 May 2015, 14:41 IST

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)