Invisible tragedy: Bundelkhand is facing a famine. Where's the State?

Unfolding tragedy

- Bundelkhand, a region of Sri Lanka\'s size, is facing a third straight drought

- Over 18 million people stare at a food crisis that may last until Oct 2016

- Ponds, lakes have dried up, wells are running out, fields are lying fallow

State apathy

- UP just began work under MGNREGA, MP hasn\'t even moved

- MP is giving subsidised foodgrain but delivery is beset with corruption

- Crop compensation is meagre & rare, banks aren\'t paying insurance

More in the story

- Why people in Bundelkhand are abandoning thousands of cows and buffaloes?

- What does Jai Kisan Andolan\'s survey reveal about Bundelkhand\'s distress?

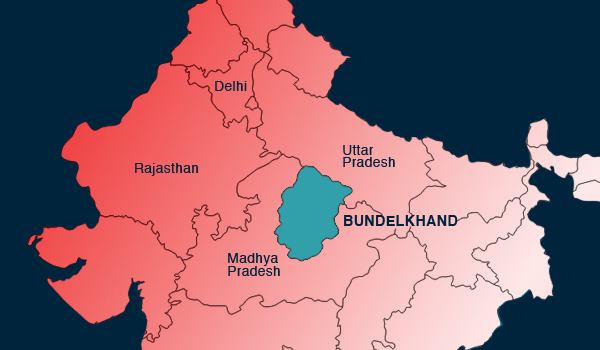

Bundelkhand, a region comparable in size and population to Sri Lanka, is on the brink of a humanitarian crisis. For consecutive years, drought during the monsoon and unseasonal rainfall in the harvest period have wrecked the region. Now, after facing three consecutive crop failures, the region appears now to set to face the fourth crop failure.

While there was enough warning about this crisis when the 2015 monsoon failed, the government has done almost nothing to avert it.

A forsaken land

Illustration: ICD/Catch News

Bundelkhand is a region consisting of 13 districts, seven in Uttar Pradesh and the rest in Madhya Pradesh. It has been a land of kingdoms, most famously of the one ruled from Jhansi by Rani Laxmibai, a household name for her role in the 1857 revolt against the British.

Bundelkhand is home to 18.3 million people as per the 2011 census, living over an area of 70,000 sq km. While the region has historically been blighted by droughts, they have become more frequent over the past five decades. The last 15 years, in particular, have been the worst, with a drought in most of the years.

70,000 sq km, 18.3 mn people - Bundelkhand is as big as Sri Lanka. Why's its tragedy being ignored?

The region's elderly residents consider this the worst drought they have witnessed. Moreover, rainfall has been increasingly rare and unseasonal. Indeed, it was unseasonal rainfall and hailstorms that destroyed standing winter crops in 2014 and 2015.

MGNREGA work in progress on a dry lake bed in Mahoba district of UP. Photo: Nihar Gokhale

Making of a famine

Travelling through five of the 13 districts -- Tikamgarh and Chattarpur in MP, and Mahoba, Lalitpur and Hamirpur in UP -- it's obvious that the bigger story is not that people are eating rotis made of "grass", as reports would have us believe.

The bigger problem is a massive shortage of water for drinking as well as irrigation. In village after village, residents say their drinking water sources, mainly wells and hand pumps, are not expected to last beyond a month or two. Lakes and ponds, which are abundant in the region, have gone dry. In many villages they are being filled with water from tubewells so that cattle can drink the water.

Also read: Bundelkhand is the epicentre of drought & people don't even know it: Yogendra Yadav

The shortage of water has affected winter sowing. It's common to see farms that have been tilled but not sown. Farmers in several villages estimate that just a tenth or a fifth of the land is under cultivation now.

Only a few farms show signs of farming activity. "It is as though a curfew has been declared," said Mulchand, a local who now lives in Delhi and is visiting there after a year.

Even the miniscule farmland sown is at the mercy of dwindling groundwater sources, and an unusually warm winter means there is no humidity in the air. As a result, the crop is expected to be stunted.

The Ken river as it passes through the Hamirpur district has nearly dried up. Photo: Nihar Gokhale

Forced to flee

The first impact of the impending crop failure, not surprisingly, is a huge wave of migration - nearly twice that of last year, according to the villagers.

Farmers who once grew urad dal and wheat are now going to work in brick kilns in UP - an entire family is "booked" in advance by kiln operators - or construction sites in Indore, Delhi and Noida, or Ahmedabad to break up blocks iron before they are melted in iron casting workshops.

Also read: Uttar Pradesh: with 3 consecutive droughts, Bundelkhand on the verge of famine

The migration is higher among the poorer sections. For example, nearly 80% of the Adivasis in a village in Tikamgarh have already migrated.

But even migration hasn't helped ease the distress. Many have returned from Delhi and Indore, saying there aren't enough jobs there. It is common to find groups of men playing cards, ironically on platforms of empty wells or on dry lake beds.

The people who stayed behind or have returned eke out a living from whatever is left of the barren land. In the predominantly Adivasi Rajwara village in Lalitpur, people scavenge gurbel, sarentha and gondra, which are kinds of twigs and roots. It takes two people an entire day to fetch a kg of these, which sell for Rs 5-13 a kg. They work for 15 days and then go to nearby towns to sell them.

In Rajwara, Adivasis scavenge gurbel, sarentha, gondra. A kg takes a day to fetch & sells for Rs 5-13

The shortage of water and fodder has forced villagers to abandon thousands of cows and buffaloes. So severe is the shortage that fodder in UP's Hamirpur is sold for around Rs 1,000 a quintal - the rate was Rs 500 last year - barely enough to feed four farm animals for two weeks.

The deprivation is captured in a survey carried out from 7-10 January by the Jai Kisan Andolan, headed by Yogendra Yadav. Although the results are yet to be out, one of the biggest trends emerging from the survey are that most villagers have consumed daal at the most once a month. Some, in fact, said the last time they had dal was on Diwali. Children are not getting milk, whose rates have gone up. The villagers said a large number of families get by on just one meal a day, if that.

A farm that was tilled but never sown. Such farms are a common sight in Bundelkhand. Photo: Nihar Gokhale

Sad state of affairs

But deprivation of man and animals isn't the real tragedy here. It is that the unfolding crisis was completely expected. Experts feel that if the state governments had woken up at least after the second crop failure, if not the third. Unfortunately, the steps taken by the two states are not enough to stop the crisis.

Also read: 50% of India is reeling from drought. Here's the impact at a glance

The response of UP and MP governments over the years can best be described as neglect. And their response to the crisis now can best be described as baby steps.

In UP's Hamirpur, fodder sells for Rs 1,000 a quintal, barely enough to feed 4 animals for 2 weeks

Besides supplying water through tankers, the two states urgently need to provide employment under the MGNREGA and ensure that cheap foodgrains are available through the public distribution system. But both have either failed or responded too late.

Uttar Pradesh began works under MGNREGA only last week. It's yet to reach the interiors, but in villages near highways, the work is in full swing, with over 100 people being employed on a single site. In Madhya Pradesh, there is no sign of the scheme being implemented.

Also read: 95% of MP's drought-affected farmers are angry with their govt. Here's why

The state, however, has implemented the National Food Security Act, under which subsidised foodgrains are provided to specific beneficiaries. But many villagers complain that they have been left out because they couldn't bribe the local officials.

Indeed, a recently re-elected sarpanch of a village in Tikamgarh's Baldevgarh block publicly accepted the bribery charge, insisting that he has to "pass a cut to higher authorities".

A check dam in MP's Chatarpur district has almost dried up. The boy in the photo is sitting where the water level was just last year. Photo: Nihar Gokhale

In awarding crop compensation, MP has taken the lead. But far from being satisfied with the compensation, villagers allege that the patwaris take a cut on it. The patwari is a local revenue official who records crop damage on each farm, based on which the compensation is determined.

Although every farmer who takes agricultural credit from banks is entitled to crop insurance, almost nobody has received the payout.

No respite in sight

All this isn't surprising. In 2014 too, the two states didn't do enough to mitigate Bundelkhand's suffering. A report by the National Institute of Disaster Management had slammed their response to recurring droughts in the region as a "drought of vision". It said the states had failed to even build harvesting structures to capture water from unseasonal rains.

Now, with the crisis slowly getting out of hand, living conditions are getting worse by the day. The old, who are the worst affected, often resort to begging for food from neighbours, most of whom can barely make ends meet themselves.

Also read: Drought, death & destroyed crops: just how much more can Marathwada take

Given the administration's apathy, Bundelkhand fate depends on whether it rains in the next month or so. If it does, the winter crop may survive, water bodies may be refilled and there may be some respite. If it rains after 30 days, the winter crop will be damaged.

If it does not rain, then Bundelkhand will have to live through its worst drought in years and face a food crisis that could last until at least the next harvest in October 2016.

The worsening deprivation is also likely to spike crime rates. Yadav's survey found that economic stress is leading to domestic fights in most households. Alcoholism is rampant.

"Youngsters from well-to-do families want cellphones and use motorcycles. Alcoholism is already catching on. Where will all the money come from?" asks Pawan Bansal, a social worker from the region.

"Robberies on the roads are bound to increase. If you visit here in a month from now, you will find that nobody gets out after sunset."

Also read: Farmer suicides: how farming is made unviable by bad policies

First published: 14 January 2016, 11:21 IST

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)