India gets its own GPS: here's all you need to know about the IRNSS

The mission

- ISRO\'s latest mission, the PSLV-C33/IRNSS-1G, was successful

- It placed into orbit the seventh and final satellite needed for India\'s own GPS system, the IRNSS

The system

- The GPS system we are familiar is owned by the US military, and comes with its limitations

- Now, India doesn\'t need to rely on anyone else for all its civilian and military GPS uses

More in the story

- What is the accuracy of the IRNSS?

- Which other countries have their own GPS systems?

- What important uses can the IRNSS be put to?

The Indian Space Research Organisation is not new to putting satellites in orbit using its famed PSLV rocket. But the latest successful mission on 28 April, called PSLV-C33/IRNSS-1G, was special.

It put the seventh and final satellite of India's own GPS system into orbit, and with it, India fulfilled its decades-long desire to have its own satellite-based positioning systems.

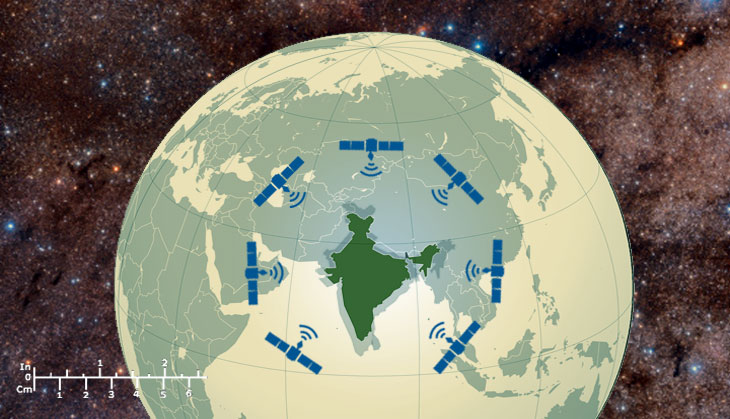

The latest satellite completes a constellation of satellites known as the Indian Regional Navigational Satellite System (IRNSS), which will have a dedicated gaze towards India, and an arc up to 1,500 km from India's borders.

GPS restrictions

This is different from the GPS that smartphone users are familiar with, which is actually a property of the US military, with 32 satellites in orbit. So far, all our navigation - whether for Ola cabs or for military activity - was in American hands.

But such foreign systems come with limitations - they can restrict how much information is available, and also potentially scramble or switch off the system.

While this isn't a big problem with civilian uses of GPS, it is a disaster for military preparedness. Such systems are also used for guiding missiles to targets, as well as helping armies track and plan their movements in conflict zones, so quality was also a hurdle.

Indeed, the need for the IRNSS is said to have been felt during the 1999 Kargil conflict with Pakistan, when India required some precise coordinates of enemy troop movement, but was refused by the US. The IRNSS puts India in control.

Ahead of China and Europe

India is not the only one to have developed this. Russia has a system known as Glonass, while Europe is developing one called Galileo Quasi Zenith Satellite System. Even China is developing one called the BeiDou Navigation System.

More than simply owning the system, the IRNSS helps overcome a peculiar problem with the American GPS, which is coded such that only the US military can get high accuracy information from it.

The rest, including India, had to do with low accuracy, which is an issue with military applications like guiding missiles, where precision is needed.

To solve this, India entered into an agreement with Russia to use the Glonass, which did not carry these restrictions. In fact, India's BrahMos cruise missile is programmed to be compatible with Glonass.

Glonass was also slated to be used for civilian purposes, including for transportation and for police use. But while talks about using it have been on for more than a decade, the adoption of Glonass has been delayed, due to "organisation and technical reasons".

Having the IRNSS will free India's dependence on Glonass. It will also have the scope for better accuracy.

Precision matters

The IRNSS is said to have software than can reduce errors in data caused due to atmospheric disturbances. While the IRNSS promises an accuracy of under 20 metres, some field trials are said to have resulted in a seven-metre accuracy.

This is because, additionally, since the IRNSS satellites will be nearer than other satellites, they'll enhance the capability to know the precise coordinates of a location, according to PK Joshi, a faculty member at Jawaharlal Nehru University and an expert on geoinformatics systems.

The IRNSS has two services - one for civilians and the other for military. The latter can deliver locations with an accuracy of 10 centimetres.

This is important, since the range of IRNSS includes not just the country, but up to 1,500 km from its borders - which includes most potential conflict zones.

The IRNSS also offers hope for higher accuracy in civilian uses. One way is for it to be used along with a system known as GAGAN - developed by ISRO and the Airports Authority of India. It improves GPS signals by adding information from a set of Indian satellites and ground monitoring stations; as a result, it can guide aircraft with a precision of 1.5 metres.

IRNSS can similarly be used in conjunction with GPS and other systems to deliver high precision location.

Important uses

The uses for the IRNSS include making high accuracy digital maps of city and town areas, forests and coastal areas. Here, the error of 10 metres and above has been an impediment to regulation.

In coastal regulation, for example, since the location of the high tide line is subject to such an error, the coastal regulation zone carries the same error, and on the ground, it translates to ambiguity over whether a particular set of houses or shops fall under it.

This is also important in forest management. There is ambiguity over where a forest area ends and revenue land begins, leading to conflicts between the two departments. A Haryana forest service official said that in areas like Gurgaon, "even an inch is important".

While high precision GPS systems are available, they are costly (ranging from Rs 5-20 lakh apiece) and can require almost 12 hours to deliver accurate coordinates.

The hope with IRNSS is that it can deliver, along with GAGAN, better precision than GPS.

First published: 28 April 2016, 10:08 IST

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)

_in_Assams_Dibrugarh_(Photo_257977_1600x1200.jpg)