A Syrian Love Story: Giving the Middle East crisis a human face

If you type Syria, Google returns three search prompts -- war, crisis and refugees. Sean McAllister's directorial efforts might result in another, highly unlikely, prompt that might just be included soon: a love story.

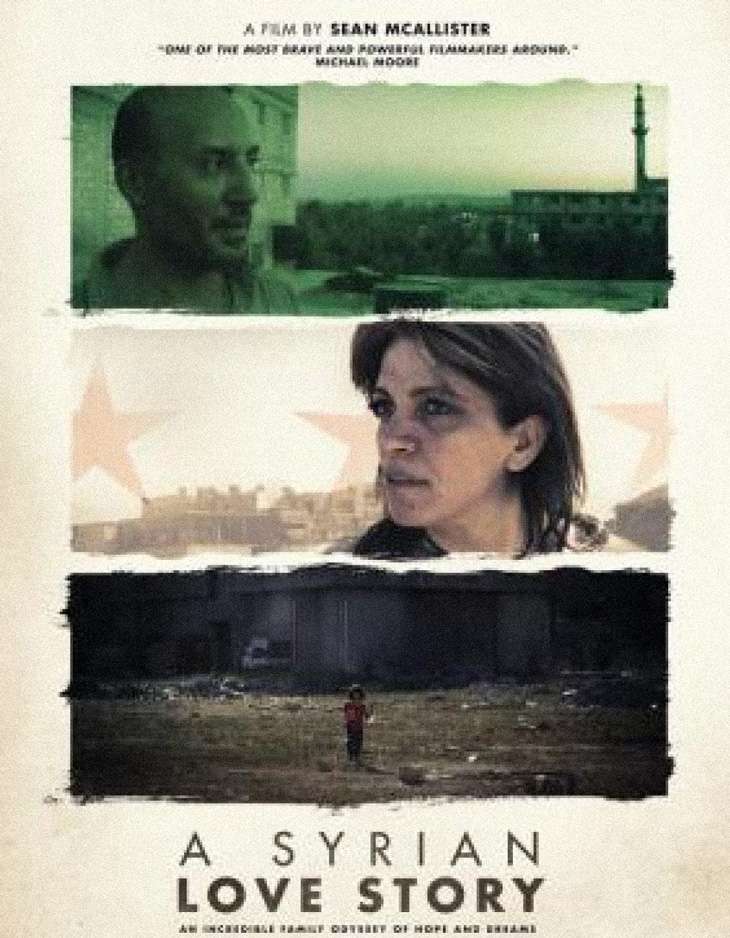

Prolific British filmmaker McAllister's latest documentary, A Syrian Love Story has been making all the right noises in the festival circuit (including a 2016 BAFTA nomination, and a Sheffield Doc/Fest Grand Jury Award). It was most recently screened at the Dharamshala International Film Festival 2016. The film follows the life of Amer Daoud - a Palestinian freedom fighter and Raghda Hassan - a Syrian revolutionary. The couple met each other in prison and that's basically when their romance started.

Through their turmoil laced love story, the film manages to show the fragmented life of a young couple who've been in love for far too long, and in Syria, even longer. They leave Syria to rebuild their lives away from the rubble of the Syrian revolution, but Raghda - more invested in the fight against the Syrian regime - cannot quite give in to the "normal life".

The canvas of Syria and its revolution is a familiar one. The home video style way of shooting is nothing new. McAllister doesn't really believe in filming objectively as such. He's in the film, navigating the main protagonists' lives as much as you are. In fact, at some point during the shooting of the film he's also thrown into prison.

That doesn't stop the scope of the film and if anything it's enhanced. We also get a good look into the mind-scape of their kids Kaka and Bob - their anger at the regime, but also cynicism at the way their parents hold on to the ideals of their revolution. Kaka says it best - they're caged in their minds.

In this interview with Catch, McAllister talks about his experience of sharing an intimate space with Amer-Raghda, how his notions of politics and freedom has changed and why Bashar al-Assad is the cancer of Syria.

Excerpts from the interview:

How did the project come about?

I first wanted to make a film set in Syria around 2009, and it eventually took about nine months to find Amer, one of the two main protagonists. So, it was a lengthy process to begin with. The whole project took over five years in fact.

What were the complexities that challenged you as a filmmaker on this project and when did you decide that the film's premise has to be around Amer-Raghda's personal relationship?

Amer had already built this huge picture of how he was in love with this woman who's in prison. When she came out of prison, I saw that the relationship wasn't as I had imagined it would be in my head. I think that's when I decided I wanted the film to focus on just the relationship these two had. The best way to look at anything political is to look at it through characters and relationships - a love story.

Did you ever feel you should step back and not film something because it seemed voyeuristic in any way?

If you're welcomed into a house and you're filming for a long time, then the material won't seem voyeuristic to begin with. You will always be able to tell in the way the camera comes into the scene whether it's voyeuristic or not.

Yes, there were some scenes I filmed which aren't in the final cut, which were stronger and more intense. After filming and as I was going through some of the material, it did seem too much and I didn't use it. There's a red line that every filmmaker shouldn't cross.

You've said you don't believe in objective shooting as a documentary maker. Since you've spent time with both Amer and Raghda, and know their politics so well, whose life choices do you now identify with?

In a funny kind of way I accept them both. I know what Raghda has gone through, her journey has definitely scarred her psychologically. But I still sympathise with Amer. I feel that without his strength a lot of things in the family would've fallen apart. He's really held it together for everyone else.

Their kids don't identify in the film as Syrians as such and they're clearly more cynical. As an 'outsider' do you feel they should persist with revolution or seek out a future which will invariably be outside Syria?

The young still have a responsibility of being Palestinian, because of their birthright, but in all honesty they'll need to look towards their own future - selfish as it may seem, instead of joining any fight. It's more difficult for the parents.

How has the way you look at Syria and its politics changed over time?

I definitely feel more political and angry now than before. It wasn't cool in the early days to get involved and say let's do something. It was cool to say that don't get involved because it's just going to lead to destruction. And now look where we've gone, it's like half a million dead.. a genocide, no less.

Obama sets a red line, Assad crosses it and drops chemical weapons on kids - and he does nothing. Instead, he gives Assad the green light to carpet bomb Aleppo. Then Putin steps into the mix as well... The core problem, we have to understand, is Assad. The cancer of Syria is Assad.

How has your idea of freedom changed, especially as you're coming from a country with colonial baggage?

In the more despairing moments of madness, I've had conversations around freedom as a relative concept with others. At the beginning of the revolution, I filmed someone saying, 'we could be less free after the revolution than we are now.' I remember the beautiful places I used to go to in Aleppo. All the lovely bars, cafes and restaurants. I loved Aleppo. It was the most gorgeous, enchanting place. But all of that's gone, it's been sacrificed and to what end?

In the current mess, the dilemma you're faced with is that there was a certain manner of freedom under Saddam in Iraq or Assad here. But I feel torn talking like this when I feel, after spending so much time with them as well, that I should be supporting the revolutionaries. Those are people who feel betrayed by the international left. All my leftist friends in England sided with Assad because he was the guy showing the finger to America, and secularism was protecting against the Islamic revolution etc. Those friends are now supporting Putin, because they feel the whole thing has been orchestrated by America. Which is nuts.

I think America was happy with the Assad regime because it sorted the region out for them. Why would they want to turn that equation upside down? But in the core of my heart, I look at the mess now and the dictator who's filled prisons with political prisoners. The dictator who was kidnapping and terrorising people who spoke against him. However, those who weren't speaking against him, and that was the majority, they had a life which they don't now.

Having spent time with a lot of people, how many pro-Assad people do you know who've changed their minds about his politics?

I know a lot of pro-Assad people who've gone right behind him more than ever. The problem with the revolution is that 47% is against Assad and 47% is for him, and then the mix of people in the middle who don't know. There are more people who don't like him sure, but I don't think there will be many who would risk three generations of their family being in turmoil over a revolution that might fail. Better the devil that you know, right?

First published: 12 November 2016, 12:04 IST

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)