Migrants aren't statistics: three heartbreaking stories show why

"Migrants undergo perilous journeys, risking drowning, deportation, arrest, physical and sexual violence in true hope of finding a place of greater safety and economic opportunity in a distant country," reads the introduction to documentary filmmaker Ashvin Kumar's new film I am Not Here.

But sometimes that freedom remains a distant dream.

Most stories do not end happily. In the chaos and confusion of fleeing their homes to search for safety in another country, most refugees lose virtually all their rights as well as their material possessions.

Many also lose their families and friends trying to cross oceans, seas and vast tracts of land.

And even when you get to land, you're not safe: 71 migrants crammed into a truck suffocated to death in a truck in Austria in late August.

Kumar's film presents the stories of three women who undertook such journeys. He also shows a heartbreaking truth - how the hope for a better future remains only a hope at times.

The film may focus on three women, but the numbers are staggering: currently, a record 60 million people have been displaced from their homes - the most since the end of World War II.

You can watch the film here:

Stories like those of Aylan Kurdi, the Syrian boy whose body washed up on a Turkish shore bring the crisis in focus for a fleeting moment.

In an interview, Kumar and co-producer Christina MacGillivray discuss why they chose these three stories, what drove him to make this film and how filmmakers have to "contend with attention spans that are unrealistically short".

Edited excerpts from the interview:

Helplessness, fear and courage are dominant strains in the film. What are the other stories you came across while researching I Am Not Here and why did you pick these three?

There were dozens of women we spoke with across multiple countries before selecting the final three women. Actually, we found Jennifer (New York) and Fanny (Zurich) before we found our final third subject in Kuala Lumpur.

After we found them, we thought we would find another subject here in Delhi. Due to complications over the status of migration between India and Nepal and the refugee status of others - we ended up recalibrating our sights on Malaysia.

MacGillivray: In Malaysia, I spoke with many women who had stories nearly as horrific as the girl in the film. I remember ending those days with a tremendous feeling of heaviness after taking on just a small glimpse of what they have gone through in search of a better life.

For all of the women who shared their stories - it was an act of courage and bravery. We have to remember that many of these stories go untold because the risk of detention, deportation and violence is too great.

The Bangladeshi girl in Malaysia went through a terrible ordeal. Was her story the most heartbreaking part of making the film?

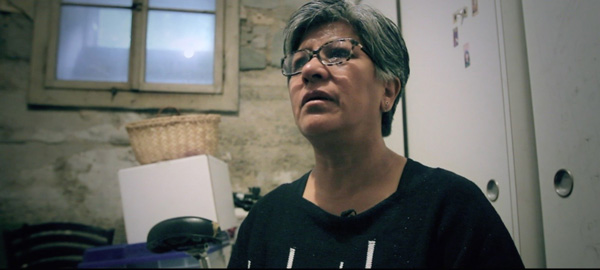

A still from the film

Absolutely. It shook me to the core. I have a lot of faith in humanity and tend to give it the benefit of doubt. I try not to pronounce judgment too easily. In fact, being judgmental is something of an occupational hazard when you're dealing with matters of the human condition.

But in her case, it was impossible not to condemn the perpetrators in the strongest terms possible. To add to it all, they will go scot free for destroying this young girl's life. Worse, who knows which other young girl they have working at their home even as we speak - who may well be going through exactly the same torture she faced.

When the Malay authorities are made aware of such heinous crimes, it would make sense that they'd restrain such people in some way. But no. That hasn't happened - which is incredibly shocking.

Considering the world is facing the worst ever refugee crisis ever, how does this film contribute to the discussion?

MacGillivray: The film was commissioned by OHCHR (Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights) to bring the voices of migrant women in an irregular situation into the room where policymakers are discussing laws and regulations that will have an impact on these women.

In many cases, migrants are spoken about in terms of large figures, statistics and represented on graphs. This film attempts to bring their voices into the room - to share the humanity that is the most important thing to remember in these discussions.

As we see with most international crises, like Syria and now with ISIS, the world gets bored of one subject and moves to the next. Does the general apathy frustrate you?

We are becoming addicted to shocking news. If it isn't shocking enough, it doesn't get you enough eyeballs. This is a disturbing trend you see in all forms, be it music, cinema, documentaries.

Today, to go in with a proposal for a film to be funded or a music album to be produced, you have to contend with attention spans that are unrealistically short. You start making work for that attention span.

Migrants are spoken about in terms of statistics. The film tried to bring their voices into the room

Life is hugely complex and people don't behave in broad strokes. A lot of our news and information, equally, gets short shrift and then loses nuance. We then end up with a pop version which retards our understanding of the world. And when you think that public opinion is formed on the basis of this, it is disturbing.

A still from the film

What will the audience take away from I Am Not Here?

A sense of indignation, I hope. A lot of us have domestic help in our homes in India, so I hope to create a sensitisation of what people endure to make sure we live comfortable lives.

Also, the issue of undocumented domestic migrants is modern day slavery. But as you've seen in the film, it isn't really called that. I hope people will see this as a serious problem.

We can only hope that the countries that have been mentioned in the film develop proper protections and laws. These women and migrants are needed for the economies of the countries they work in.

They (by and large) are honest and want to pay taxes. It would make sense that policies are re-written keeping in mind the globalised world and movement of labour rather than the rigid nation-state boundaries that are an idea of the past.

What's next for you?

I am making a film called Noor, a teenage coming-of-age story about a girl from England who comes to Kashmir looking for her father.

It's a story of hope against the reality of the conflict. It's the story of women and children - the next generation - of Kashmir. I am presently in the UK looking for funding for the film and trying to put together the cast to start next year.

Your films have usually run into controversy because of their subjects. Yet you have won a national award and an Oscar nomination for Little Terrorist. How does it feel?

With such powerful subjects and stories that I've had the privilege to film, I am too busy trying to tell their story to occupy my mind with trying to outdo myself. I think the day I start doing that, I'll stop making films.

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)