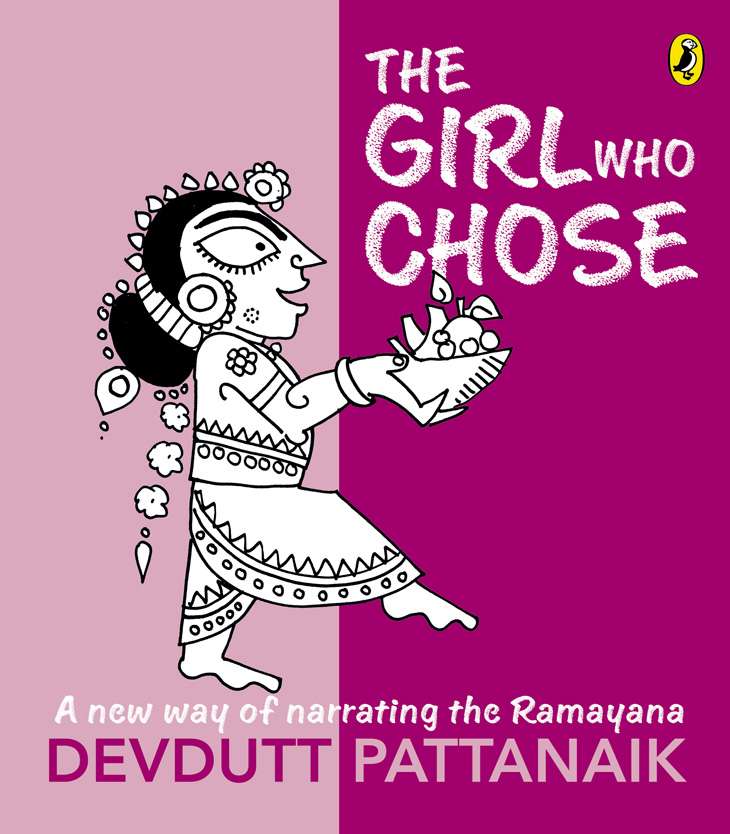

Devdutt Pattanaik's Ramayana: celebrating Sita's power to choose

"You are bound by rules, but not I. I am free to choose. I choose to follow you," says Sita calmly when Rama tells her that the forest is not a place for a woman, as he prepares to leave his princely comforts of Ayodhya and relegate himself to 14 years of wilderness.

But Sita chooses to go. And that's the first choice she makes out of five choices which determine the plot of Valmiki's Ramayana.

At the outset of The Girl Who Chose, Devdutt Pattanaik's retelling of the Ramayana, the author explains, with masterful simplicity, the difference between good and evil, between the rishis and rakshasas.

"Humans believe they should control the earth with farming and the mind with rules... Humans use choices and rules to create a world where there is more kindness and less cruelty." Rakshasas, on the other hand, like animals, live by instinct, living purely for self-interest. Hence the conflict.

Some humans twist rules to serve their interest. When Kaikeyi asks Dashrath to keep up his promise of granting her a boon and send Rama to the jungles for 14 years, Pattanaik points to her son Bharat's thinking: "Rules surely existed to help people, not to hurt them."

But the world is complex and somebody's rule is another's punishment, as we see all the time. That is where the agency of choice comes in. To Pattanaik, therein lies Sita's greatness.

The power of choice

Two themes keep recurring throughout the book - the commitment to be bound to rules, which defines Rama's personality, and the freedom to choose, which Sita is empowered to do.

Both are often in conflict, difficult to exercise, and neither exist in isolation.

Rama abides by rules, but chooses to not get remarried, even when the rules allow him to. Sita exercises her choices, but also feels bound by some rules of social conduct.

For instance, when she is banished to the jungles after her return to Lanka, she gives birth Luv and Kush and we learn that she trains them in warfare (being an avatar of Kali). So adept are the boys that they defeat Rama's entire army from Ayodhya. But why did she not fight Ravana herself when he was kidnapping her? Why did she instead choose to wail and drop a trail of her jewels for Rama to find her?

Even when she has the option of fleeing Lanka with Hanuman, Sita tells Hanuman: "I want my husband to cross the sea, come to Lanka, kill Ravana and rescue me himself, thus restoring the reputation of his family. For Rama is a prince, and royal reputations matter a lot to princes."

What is interesting is also the lesson to respect somebody's choice. When Surpanaka desires Rama and he politely refuses, she attacks Sita, hoping that with her gone, Rama would take another wife. "Clearly, she was a rakshasa who did not care for other people's choices, but only about her own desire," espouses Pattanaik.

Sometimes the act of giving a choice is a bit over-emphasised.

One of the most heartbreaking parts of the book is when Rama, after killing Ravana and rescuing Sita, says detachedly: "I have defeated the man who had kidnapped the queen of Ayodhya, the daughter-in-law of my family. And therefore, I have saved my family's reputation. Now, Sita, you are free to go wherever you wish."

Rama seems so obsessed with rules that he has almost forgotten what it means to love.

Speaking to Catch, Pattanaik explains: "(Rama's statement) is an expression of what he is expected to do as a scion of the royal family. We 'moderns' may not like it. But that is the story. It is about unquestioning submission to family legacy. Like a soldier at war who is not allowed to question who he is shooting - he must do what he is told to do. That is why the life of a soldier is so tough. Violence is based on state directives, not individual choice. Soldies have to live with blood on their hands. No medal can take away that moral horror."

The notion of 'flawed' gods

When Sita again chooses to go back to Ayodhya with Rama, gossip tears apart Sita's reputation. She was with another man. Rama deserves better. And Rama, being a people's king, banishes Sita to the jungles once more.

When he defends his decision to his own abandoned children, Luv and Kush, he appears flawed at various levels. Why, then, was Rama ever a great god?

"The notion of 'flawed' god is based on modern judgment, and incidentally that concept of 'judgement' is part of Abrahamic, not Hindu, mythology. Would you consider a hemp-smoking Shiva to be 'ideal'? Is Krishna 'ideal' for loving many women and being faithful to none? Is Parashurama 'ideal' for beheading his mother? Is Buddha 'ideal' for leaving his wife and newborn child?

"It is tough to be a soldier, who has been given no choice. As the eldest son of a royal family, no one asked Rama if he wanted to be king. Judgement is easy. Empathy tough," explains Pattanaik.

Moral lessons

In the end, Sita tells her kids: "Some people have the freedom to choose. Others don't, and they have to follow the rules. The world is full of all kinds of people."

In today's imbalanced world, do we need a society that is more rule-bound, or that exercises its freedom to choose?

"It is a function of context. Where you are and why are you doing it. Rama and Sita are doing it depending on their role as king, husband, wife, mother. They are not doing it for self-gratification, but out of concern for the other. That is the biggest lesson to learn from the Ramayana, I feel," says Pattanaik.

He is also careful to say that not everything can be a matter of choice.

"I did not choose my husband; my father and Shiva's bow chose Rama for me. Sometimes in life, we don't get to choose. But that's not always a bad thing. You have to trust, and hope for the best," Sita says.

Pattanaik's large-fonted 100-odd paged book might be one of the earliest lessons one can teach a child about consent, respect for rules and one's choices and those of others.

The message seems clear: if you have the opportunity to stand up and make a choice, don't be a wuss. Accept all its consequences with grace and strength, as Sita did.

Edited by Shreyas Sharma

More in Catch

The Vegetarian is a reminder that patriarchy is a universal language

Meet the author who gamed Amazon, and isn't going to stop anytime soon

Between the firing lines: this stunning graphic novel on Kashmir is a must-read

First published: 8 July 2016, 10:02 IST

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)