Between the firing lines: this stunning graphic novel on Kashmir is a must-read

At the age of 14, Malik Sajad began to write editorial cartoons for the Greater Kashmir. At the age of 16, enraged by his anti-Government satire, the Indian army came after him.

Except, Sajad, also known as Munnu, was in school. That meant that army officials had to wait till after school hours to meet him. When they discovered that he was just a young boy on a cycle, they reluctantly let him go.

When he was 21, Sajad was invited by the Indian Habitat Centre in Delhi to showcase his work. On September 13, 2008, Malik Sajad was in a cyber cafe in central Delhi. He was sending a cartoon that illustrated guns, to his editor in Srinagar.

A few kilometres from where he sat, a bomb went off. Then another. Then three more.

We would later remember this as the Delhi bomb blasts. 30 people would be killed. The Indian Mujahedeen would later claim responsibility.

The owner of the browsing centre where Sajad sat, recognising him to be a Kashmiri Muslim, called in the cops. A mob collected outside to watch the arrest of the 21-year-old 'terrorist'. They needed no further evidence - he was a Muslim from Kashmir.

The scrawny 21-year-old was picked up, assaulted by the police, and kept under watch at the Habitat Centre for four days. Meanwhile, in Kashmir, the army was called in to investigate his family.

When nothing was found - no militant history, no militant relatives, and a confirmation from The Habitat Centre that he was indeed a guest from Kashmir - he returned to his home in Batamaloo, in Srinagar.

Three years later, Sajad began to write a graphic novel about growing up in Kashmir.

Munnu: A Boy from Kashmir was released earlier this year in the UK to critical acclaim.

Sajad had been told that the book was not publishable in India "due to its content".

When I called Sajad and told him the book was being released in India on October 30, he didn't believe me at first. At my insistence, he consulted the Amazon India website to check. Exclaimed in happiness. Then giggled.

He eventually accepted my congratulations, knowing, more than I ever will, that they were hard earned.

In his shoes

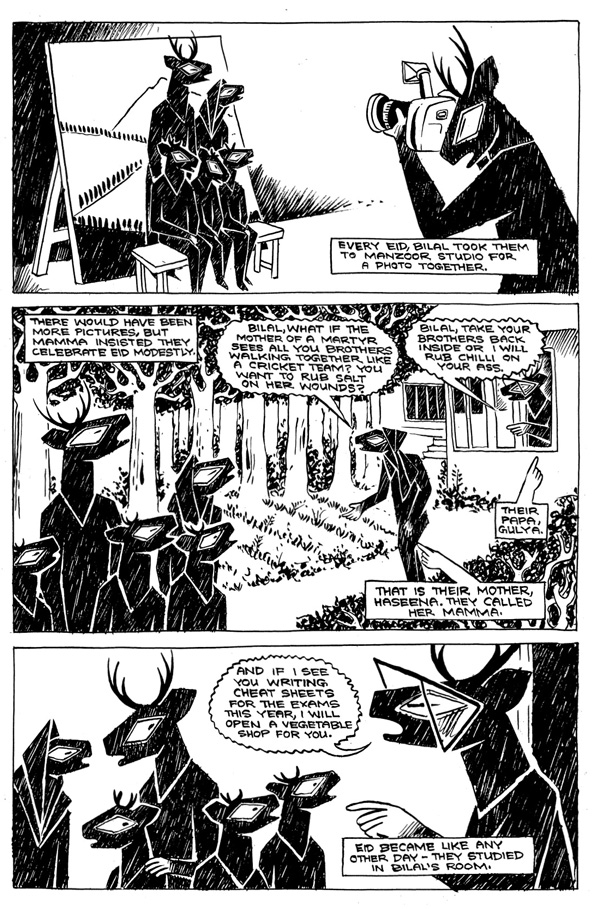

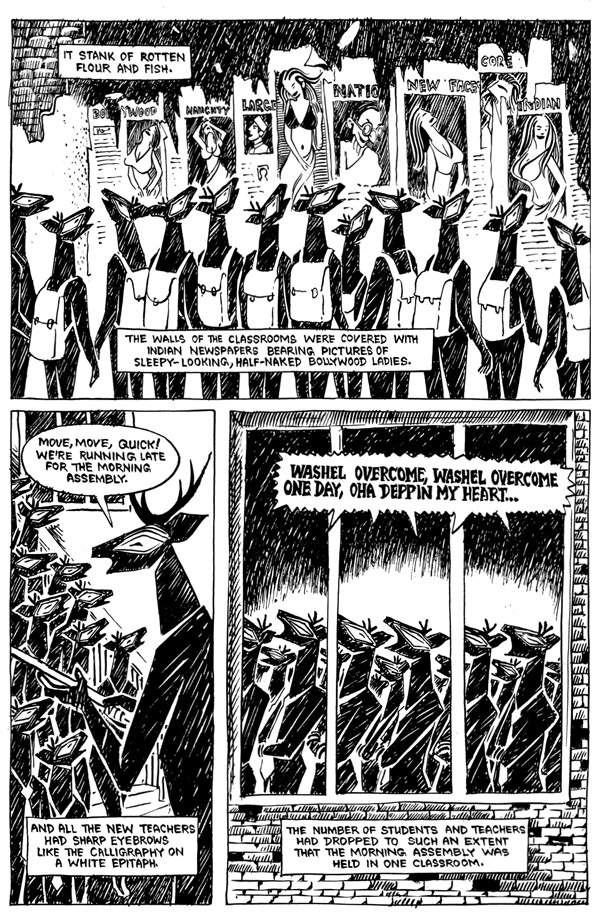

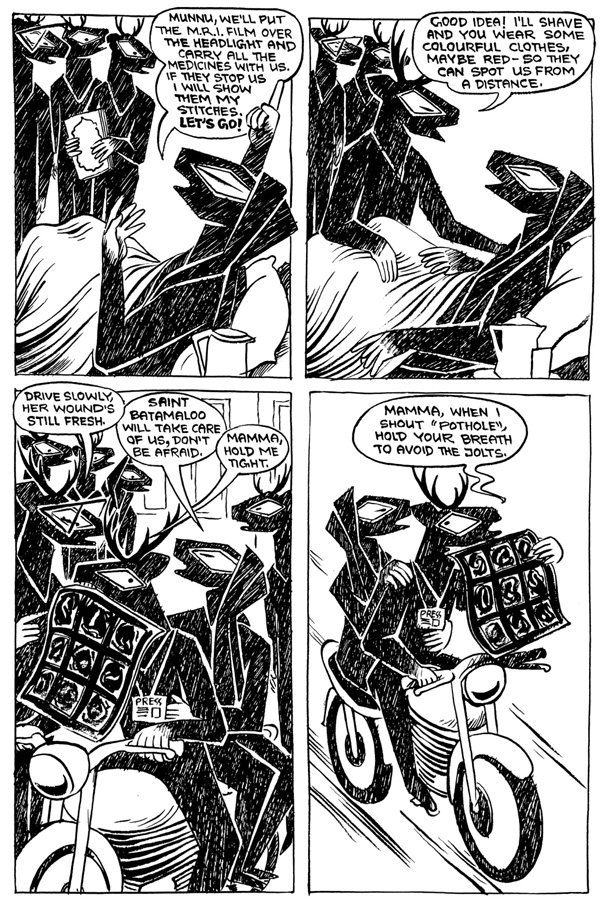

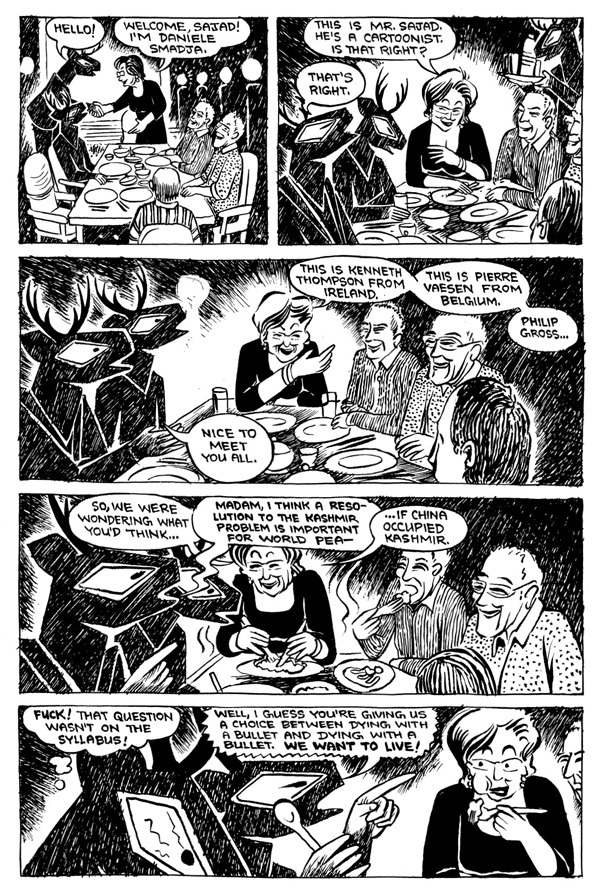

Sajad's debut graphic novel, an autobiographical account of growing up in Kashmir, depicts Kashmiris as the hangul - a dying species of Kashmiri deer. The hangul has been endangered by the deforestation and construction of the Indian Army.

This is a tool also used in the Maus series, but is nonetheless effective.

The book itself isn't quite about the flashpoints in Sajad's life. It has less to do with the politics of militants and curfews and more to do with ordinary people trying to go about their lives in a ravaged and plundered conflict-zone. Where, like Google and Uber have become verbs in our dictionaries, Crackdowns have become a verb in theirs.

He explains the complexities of a life in Kashmir - complexities that many of us would have otherwise never learnt. For example, the dangers of election season.

Voting in Kashmir is compulsory. That means that in the days immediately after the election, the Indian army searches all Kashmiris for an ink mark on their finger, a sign that they have indeed voted.

Militant separatists also search for the same irremovable ink mark, but with the opposite objective. Finding it on the fingers of a Kashmiri means that he or she sympathizes with the Indian government. That Kashmiri is a traitor.

This is the worth of what Malik brings to the Kashmir question. He neither aligns with the Indian stand, nor sympathizes with separatists. He simply relays the lesser, every-day tragedies that have been lost under the cries of grieving mothers and wives.

He illustrates why his parents insisted that all five children celebrate Eid austerely.

And his school walls - covered in posters to hide the bullet holes underneath.

How he managed to get his mother to a hospital during a curfew (the army had wrecked the hospital ambulance).

What it was like being invited to dinner with ambassadors from the European Union who, after suggesting that China occupy Kashmir, gifted him a solar-powered torchlight and sent him home.

He writes and sketches with an honesty and humour as disarming as it is disconcerting. The sketches, like his narrative, are frighteningly detailed.

It's unsurprising, because Sajad learned the art of visual detailing from an artisan himself.

The son of a woodsmith, Sajad began by sculpting wood works under the unforgiving tutelage of his father. He then moved on to sculpting chalk with a pin. Then, after fleetingly falling in love at age eight, onto portraiture.

He eventually discovered what Marjane Satrapi, Joe Sacco and Art Spiegelman before him did - that the mightiest weapon, one neither army nor militants think to search for, is the pen.

In his case, a sketch pen.

And though the editorial cartoons he drew for Greater Kashmir landed him in trouble with the Army as well as the militants, it hasn't affected his resolve to keep sketching. "Drawing political cartoons is a part of me. I will draw for the Greater Kashmir for as long as I can," he says.

Don't mistake his resolve for belligerence though. Sajad writes with the greatest kindness, giving all parties a hearing, sometimes indulgently so.

Even while speaking of those who mobbed him outside the cyber cafe in Delhi in 2008, he says "People are the same everywhere. They have the same processing mechanisms. They make their assumptions based on information that is given to them. It is the same politics that we and every person in the world is a victim of."

It is this rationalism and commitment to fairness that makes him so compelling. It also makes what he has endured even more unjust.

Asked about what was like to grow up with a window to the worst human atrocities, he says, "I know Kashmiris are considered the patent holders for terrible lives. But honestly, take a trip to Old Delhi and observe the rickshaw pullers. That, I sometimes think, is a truly horrible life."

If perspective is what the world needs most, then Malik Sajad has enough of it to go around.

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)