What makes a victim? Is it violence, sexual control, or is it psychological imprisonment?

Garrisoned Minds, a book edited by Laxmi Murthy and Mitu Verma, and penned by South Asian journalists, suggests that it's the latter. While rape and physical violence are very real threats to women living in conflict, the ultimate exertion of power appears to be in capturing their minds.

Also read - Garrisoned Minds: Listening to the silence of Kashmir's women

A garrison is a space "to (re)construct the facade of a state that provides welfare and security to people", but only inside of it. "The ability to reproduce a quality of life that is denied to those outside it is a remarkable achievement of the garrison," writes Sanjay Barbora in Garrisoned Minds.

This goes to show that the entire premise of a garrison is a life lived in denial. Either that, or a life lived outside of it, psychologically controlled by the military hegemony of the garrison.

The book is divided into four parts, each assigned a specific conflict zone in South Asia. This article will focus on Northeast India - specifically, Manipur and Nagaland.

"In Northeast India, militarisation has created a world that inverts the ability of human beings to come together. It destroys the ability of people to negotiate and create spaces of coexistence, employing instead memories of personal cruelty and anger," writes Barbora in the introductory chapter called Remembrance, Recounting and Resistance.

Barbora's observation highlights the death of debate in Northeast India. Death at the hands of the Indian Army, conflict between tribes, and regional politics.

Women fight back

Thingnam Anjulika Samom's essay The Art of Defiance focuses on the Manipuri women's struggle for emancipation. Set in the backdrop of the Meitei, Naga and Kuki people's struggles, the Northeast's tussle with the army is very different from that of Kashmir.

The essay starts with the story of Luingamla Muinao, an 18-year-old who was allegedly shot dead on 24 January, 1986, by Capt Mandhir Singh (25 Madras Regiment) and 2nd Lt Sanjeev Dubey (Mahar Regiment) for resisting their attempt to rape her.

Luingamla didn't get to go study in Imphal or even make it to class nine, but her memory was kept alive by the women of Ngainga village. They first collected funds to make a calendar and later introduced a new design in their traditional attire - the Tangkhul sarong - named after Luingamla.

Women helping women, women supporting women, women fighting for women. These are the themes that emerge from Samom's essay.

Samom historically maps the women's struggle in Northeast India right from the early 1900s where women vendors protested against the British power, to the 1970s and 80s marking the Nishaband (Prohibition) movement to the Meira Paibi movement where women took to the streets to save their children from military atrocities.

Interestingly, none of these struggles were for the betterment of women themselves. This changes markedly in the 90s.

In 1996, an Anal Naga woman, Tohring, became one of the first to publicly disclose that an army man attempted to rape her in her own room and beat up her husband. Elangbam Ahanjaobi, emboldened by the conversation around rape, revealed that she was raped by two army men from the 2nd Mahar Regiment.

"I came to know later that this person had raped another girl in the past, but the matter was hushed up. So, he had the audacity to commit the same crime again. That is why I spoke out. If I had kept silent he would continue doing the same thing to others", Tohring tells Samom.

Also read - Volga's The Liberation of Sita: Isolation offered in the name of feminism

Ahanjaobi, echoing similar thoughts, adds, "My sons and husband should know I was not at fault."

The deep-seated patriarchy in Ahanjaobi's life is evident here. But regardless of how she expresses her need to talk, she breaks free of it with her intention to help other women. And, by speaking up, she makes rape visible instead of it being a hush-hush topic that was best left unmentioned.

Incidentally, as the essay points out, she's one of the few women whose rapists got a prison sentence. "In this regard, Ahanjaobi stands alone", writes Samom.

But the case that got widespread media attention, even internationally, came later in 2004. On 11 July 2004, 24-year-old Thangjam Manorama Devi was allegedly dragged out of her home by soldiers from the Assam Rifles, tortured, violently raped and shot dead.

"...In destroying Manorama, the army sought to destroy the people of Manipur," writes Samom.

But the reverse happened. Manorama's brutal killing made the Meira Paibi women unite for a protest now etched into the pages of history.

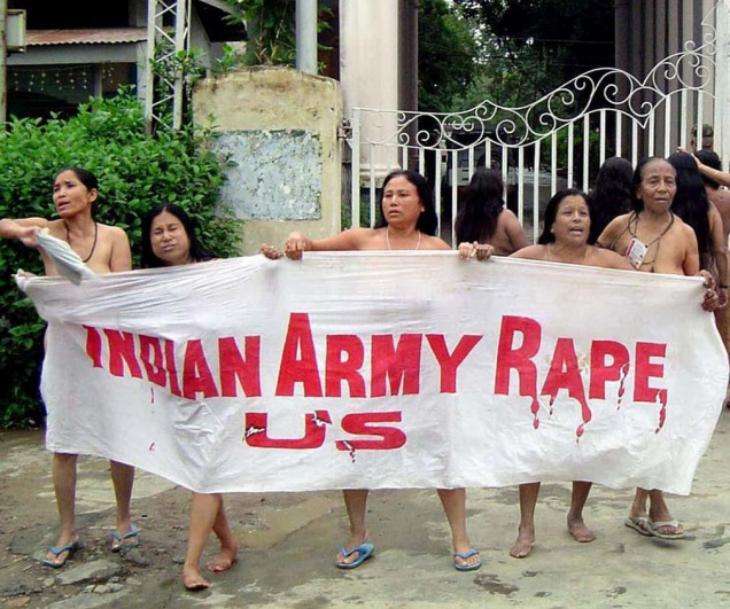

On 15 July, 12 angry elderly women stripped in front of the gate where Assam Rifles were stationed. They called out to the sentinels, waving a banner that read 'Indian Army Rape Us.'

"This was the honour of all the women of Manipur that the Assam Rifles had trampled upon so mercilessly, with such audacity. What was the use of clothing ourselves?" one of the protesters tells Samom.

Calling the body politics in this protest "the pinnacle of women-led movements in Manipur", Samom observes that it subverted patriarchy and made "a revolutionary statement insisting on a woman's right to control her body".

While the case has still not resulted in any punishment for the criminals, it definitely gave voice to many women who had been sexually violated.

The politics of fear

Perhaps army rapes are reported less because the army is seen as the weapon-wielding, righteous, protectors of our entire being. The army is romanticised for being the sacrificing entity that embraces martyrdom for our sake.

Perhaps army rapes are reported less because it is one thing to battle society and its judgement of rape victims, but it's another to hold the army accountable for violating what they're meant to protect civilians from - a threat to personal safety.

In Yirimiyan Arthur Yhome's essay This Road I Know, she talks of the constant fear she travels with. A fear she didn't have while travelling as a child through Nagaland and Manipur.

She documents her personal struggle of living in conflict. Her observations, though similar to Samom's, bring out the trauma of what a garrisoned mind becomes.

She narrates the story of a certain KT Rose, a girl blindfolded and interrogated, but never physically assaulted. "The soldiers told her they would rape her, burn her body and peel her skin off", Yhome narrates.

"To frighten her more, she was told there was nobody else in the room besides them."

"She survived the episode", writes Yhome, adding that she was "physically unharmed but psychologically scarred."

These stories play on Yhome's mind. They aren't stories she'd read in a book, but the reality of women she encounters every day. And she lives with the fear of becoming just another number in these statistics.

Yhome recalls a day in the mid-2000s when she was driving around with friends visiting from Delhi.

"An army convoy drove past us, one of the passengers spontaneously pointed an imaginary gun at them and made gun-shot sounds 'dishkyun, dishkyun'.

"The rest of us froze. She had no idea about the sense of fear that had suddenly gripped us with her playful gesture.

"Who in the rest of India... fears the army, after all?" asks Yhome.

While Yhome's narration gives us an idea of the extent of how damaging the mere threat of sexual violence can be, she also notes that the army's mind control doesn't stop at just that.

They also control women by denying them basic rights, suggests Yhome. She talks of an incident when the bodies of two elderly women were carried by women for burial as the army didn't permit them to be buried as per tradition. She mentions another where a woman is forced to give birth to her baby in a village ground and denied any medical attention.

The only solution to this madness seems to be women breaking free of this control and questioning their right to safety. And one way to break free is to identify the fear.

Yhome ends the essay with a powerful, yet measured prayer for her daughter.

"Her father narrates anecdotes as he drives and I try not to pass on my fears.

"Fears, if at all, must be gathered through personal experiences and not inherited.

"I hope she will have a different story to tell."

First published: 15 September 2016, 11:39 IST

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)