Child Labour Act: why everybody wants children to work

The law

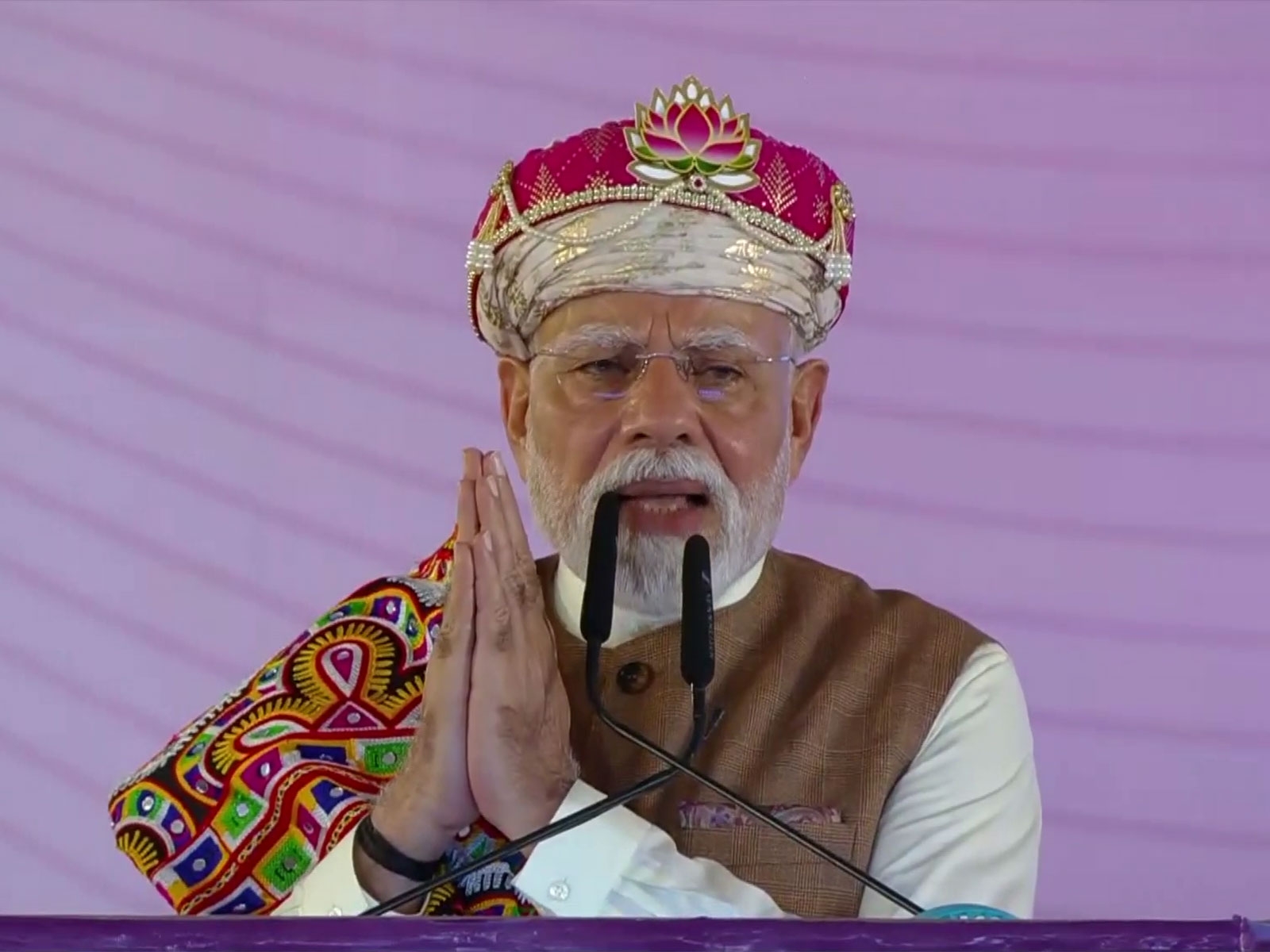

- The Narendra Modi government plans to amend the Child Labour Act.

- This would make it legal for children below 14 years of age to work in non-hazardous family enterprises.

- The govt says this is keeping in mind the country\'s socio-economic realities and it will help children acquire skills.

Definitions

- The law defines a child as someone who is 14 years or younger. 14-18 age group can even be engaged in hazardous work.

- Even the difference between hazardous and non-hazardous is arbitrary.

- Enforcing the rights of children in family-run enterprises will be difficult.

The problem

- The amended law goes against Article 23 of the Constitution which provides the Right against Exploitation.

- It also prevents the implementation of the Right to Education in its true spirit.

Raj can't wait to turn 18. He has four more years and some months to go before he can legally sit behind a wheel and learn to drive. A driver's job, he says, is most exciting - even more than creating vibrant sketches that spring to life inside his drawing book. So each afternoon, when his government school bell rings, he rushes to a neighbouring creche to teach little kids to draw.

The money is enough to recharge his prepaid phone, buy some sundries and save for driving lessons, a life necessity his family wouldn't understand. He lives with his sister who is a nanny at the creche, and her husband, a security guard, who can barely make ends meet raising their own two kids. Raj works because he has nobody watching his back.

So when the Union Cabinet passed an amendment to the Child Labour Act last month, legalising children below 14 to work in non-hazardous family enterprises, many celebrated it - the industry did because it would mean cheaper labour, the parents of child labourers did because it would mean more family income without the stress of having to operate covertly, and most of the four million kids between five and 14, engaged in child labour, many of whom work in family run enterprises because like Raj, they would be able to fast forward into adulthood and earn money - their only shot at self-worth.

The problem with little kids working

Let's start with the basic premise of the law. Who is a child? The most commonly agreed upon definition across the globe slots a child squarely as one below 18 years of age. For the first time the government of India has tweaked this definition. It defines a child as one who is below 14 years of age. The age group of 14 to 18, it says is not a child, but an adolescent.

While children can work in non-hazardous family run businesses outside school hours, adolescents can engage in any non-hazardous livelihood. Going to school for adolescents, is a choice, not a compulsory state mandate. The segregation has two reasons.

The first need to tweak this definition arose with the passing of The Right to Education (RTE) Act in 2010 which made primary school education free and compulsory up to the age of 14. In order to be consistent with RTE, The Child Labour Act had to ensure that education take precedence over occupation for those below 14. And so The Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Amendment Bill, 2012 was introduced in the Rajya Sabha on 4 December, 2012 allowing children under 14 to work in family businesses and entertainment industry (excluding circuses) outside of school hours. The government assured that the amendment was made to ensure "a balance between the need for education for a child and reality of the socio-economic condition and social fabric in the country."

After being cleared by a Union Cabinet on 13 May this year, the amendment is expected to be passed in the forthcoming parliament session.

But the other reason for the segregation in age groups holds a more subtle shift in our conscience as the culprit. "After Nirbhaya happened, child protection has eroded. The juvenile justice system brought changes where those above 16 would be tried like adults. The classification of above-14s as 'adolescents' is a move in that direction," points Sreedhar Mether, National coordinator for campaigns and advocacy at Save the Children.

While civil society groups such as Save the Children account removing child protection from adolescents, to a cascading effect of the altered juvenile justice system, others such as former NPCR head Shanta Sinha welcome the classification for finally giving focus to the needs of a fragile age group whose issues got lost when being grouped in the 'child' category.

When factories come home

"We are proud that at our age we are getting to help our families make money," came the bold response when Neha Saberwal visited some families engaged in the garment industry in Delhi and asked a 16-year-old sewing a collar, what it felt like working. Saberwal is an advocacy and campaigns coordination officer for New Delhi's Save the Children.

For generations, these families have invariably roped in their children into what they do for a living. Lines are blurred between work spaces and home, one often seeping into another without conflict.

With every generation a child is taught that survival depends on learning the family business and many are taught to take pride in it. So what's wrong with helping out at home?

A lot. Especially, when your home becomes a factory. A garment earlier had to be made in a factory. But now companies evade tax and labour laws and dump raw material in village households converting homes into a factory line style processing unit. The collars are made in one house, the button are stitched in another and thread is chopped in another. Children work on the same task repeatedly, hundreds of times a day, causing much strain to their small bodies. The trucks that are sent to pick up the finished goods also unload a fresh batch of raw material.

The cycle continues, unnoticed behind closed doors.

Would the work of a young girl scrubbing floors all day under abusive employers be considered non-hazardous?

Civil society's biggest concern is this: By allowing children to work on family enterprises, this amendment is 'invisibilising' child labour. Take the carpet industry for instance. Traditional carpet making belts were Bhadohi, Mirzapur, and Varanasi in southeast Uttar Pradesh, over populated with some of the country's poorest households.

After years of government scrutiny on child labour, bonded labour and forced labour, the industry merely shifted out a few hundred kilometres away to rural Muslim villages of Shahjahanpur, Badaun, and Hardoi. You cannot say how many informal sectors this move will send from factories to homes. Experts such as Sinha fear that Zari, papad, carpet making, and a host of others are going to cash in on the move.

Hazardous versus non-hazardous

"All work is hazardous," says Ossie Fernandes, former Union Labour minister about the government's distinction between hazardous and non-hazardous activities. A child, up to 18 years of age should be free from the pressures of employment of any kind," feels Fernandes.

Right now only 29 industries such as stone or silica based quarrying, mining, timbre handling and other similar toxic or heavy weight industries are listed as hazardous. But when a child engages in manual labour, it is hard to pin down what constitutes as hazardous in such a black and white manner.

Take the case of a child working on a cotton field, which is technically a non-hazardous activity just like any other agricultural activity. But the heavy use of pesticides in cotton plantations have adverse health impacts on children. The cotton industry has the highest amounts of child labour historically speaking and several thousands of these are harmed by the use of pesticide.

Or take the case of domestic labour which is typically non-hazardous. How would you then classify the work of a pre-pubescent girl scrubbing floors and dishes from morning to night under abusive employers? The extent of involvement, the hours of labour, the mental and physical conditions under which she functions, are all factors which make it difficult to establish the degree of work hazard.

"Ultimately, this central act needs to give more room to the states to decide depending on the livelihoods prevalent in their particular economy," offers Mether. So a state like Chhattisgarh with a majority Adivasi population where children often weave baskets, leaf-plates and make art and craft which is a part of their way of life, could have a different approach to child labour than an urban city state like New Delhi. Tailor made laws could be a solution.

What a consortium of NGOs are fighting for is for a blanket ban on child labour below 14. 'Non-hazardous', 'family enterprise', 'outside school hours', are all sugar coated terms they're not buying.

Skills versus textbooks

"What's the point having an education system where you are 18 years old without a single skill that will fetch you employment?" asked AV Swami, an independent Rajya Sabha MP from Odisha. Swami, like many others, feels that the move would be an opportunity for a child to learn through experience. "What is the harm in a child learning about his heritage and learning from the wealth of indigenous knowledge his family roots have. And what are we today? Bonded labourers to a corporate sector!" he laughed.

Civil society NGOs such as Haq, CRY and Save the Children, argue that this narrow outlook towards work culture perpetuates caste. Why must a barber's son become a barber and potter's daughter become a potter? The solution, feel those fighting for civil liberties, lies in working out a school curriculum which includes a variety of vocational and art and craft skills that students can have the freedom to choose from depending on their interest.

Enforcement

There are portions of the amendment that have gotten applause. For instance, this is the first time where they have increased the penalty for defaulters. If child labour is found occurring, the employer will be taken to jail as opposed to fined. But when factories outsource the task to adults and adults tell their children to help out, who is the real employer?

Home based institutions are the most dangerous because these are zones sealed from the eyes of any type of external monitoring system. The amendment assigns this task to district child protection units or DCPUs who are supposed to be formed in every district.

But take the case of the zari industry, when children often work through the night, do you really see a child protection officer taking the effort to break into a household for a midnight raid? Community enforcement also fails in situations like this when it is in the interest of the community to have their children working. Who will report situations of child abuse?

Its not like having the old law would fix the situation or reduce child labour in these industries, some argue. But that argument is like saying that since people are selling kidneys, we should lift the ban on it and put it up for sale in a market. What's the point of a law if it doesn't uphold the values we strive for, first in writing? What hope is there then to fix the issues of enforcement?

In an article titled India's child labour reforms could make it a dangerous place to invest, Aidan McQuade argues in The Guardian: 'The proposed reforms, taken together, are arguably unconstitutional, flouting Article 23 of the Indian constitution, which prohibits trafficking and forced labour. Future generations may come to regard this as a seminal moment in Indian history, when an Indian government repudiated the ideals enshrined in the constitution by the founders of the republic - and instead substituted a legal basis for the exploitation of vulnerable citizens.'

How often have we stopped at a traffic signal and seen tiny knuckles rapping on our rolled up AC chilled car windows greasing it with their sweat and grime, asking us to buy a plastic windshield, shrivelled roses, a cheap box of tissues or cheap petroleum smelling rubber balloons?

How often we've turned away with a moral high ground and said naively that we don't support child labour - as if not giving the child some business will drive him to get an education at school and eventually a respectable job. With the new law, these 'family businesses' will be legal. Letting these amendments pass in its current stage amounts to pouring water on our own Constitution and declaring that we give up on the future of four million kids.

First published: 4 July 2015, 2:59 IST

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)