What is remembered: A book on Indian immigrants & identity crises

You are that Indian who dreamed of living the good life in New York. You succeeded. Enough to never be counted amongst smelly Indians, enough to take pride in being mistaken for a non-Asian, enough to never have missed home or that silly institution called family.

You push the memory of India and all-things Indian to the farthest corner of your brain. You are aware that recall from that corner is poor, but you are willing to take a chance because you have little to lose. How could personal memories - such as the name of your mother - matter in this brand new, fantastical life, you wonder?

It's been 14 years since you turned your back towards India, since you gave your mother, your village, your country - a thought. You've forgotten the name of your mother. And you are certain that such trivia doesn't matter in your hugely successful new life. Or afterlife.

But then your gods, the Americans, order you to fill out forms - so that you cease to be an Indian, so that you become one of them - at least on paper. You jog your memory to remember the trivia. Zero luck.

What would you tell the gods?

You are forced to take a trip down memory lane, to your port of arrival in the US, where you think you could find clues to your past.

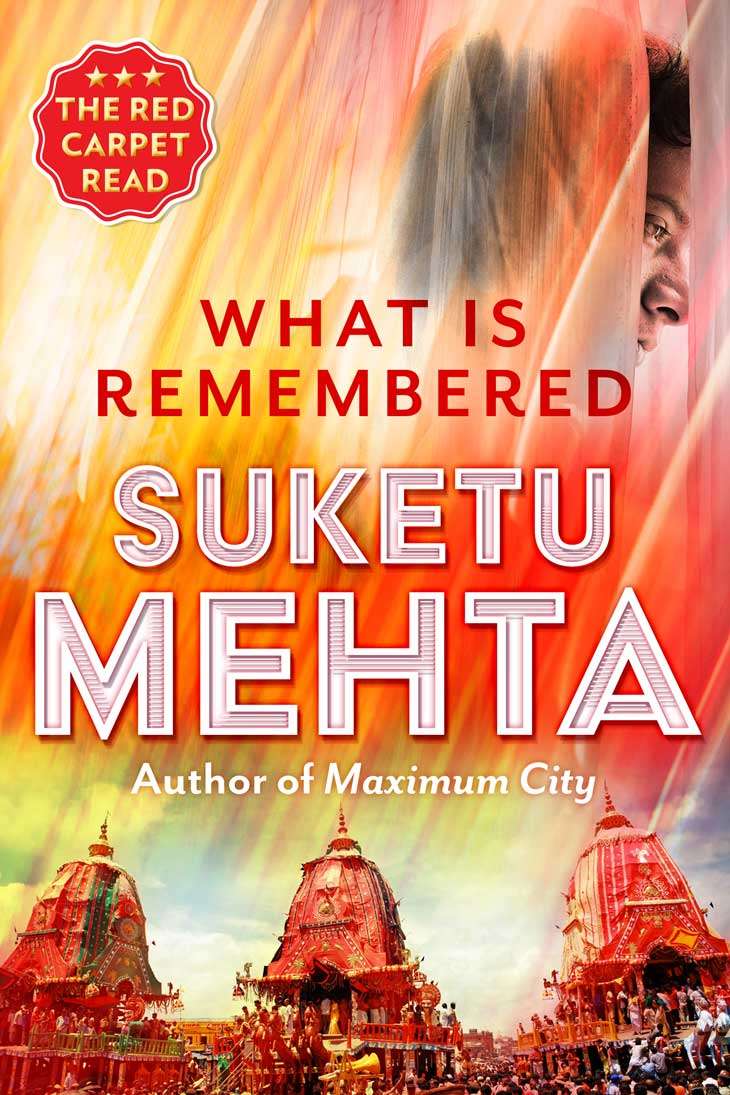

This journey, the shuffling between your gains and losses, between your real and imagined memories, has resulted in What is Remembered. Suketu Mehta's sharp, sad and witty 52-page novella exclusively available on the Juggernaut Books app about an Indian immigrant's life in New York.

Maximum City

Suketu Mehta is back on the literary circuit after a gap of 12 years. His first book, Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found picked up prestigious awards and Mehta was a finalist for the 2005 Pulitzer Prize.

He left Bombay in 1977, at the age of 14, but it was the city he referred to as home regardless of where he lived - New York, London or Paris. He came back 21 years later to find "his Bombay" and Maximum City was an ode to his beloved city.

With What is Remembered, Mehta zooms in on the life of Indian immigrants. Ironically, Mehta wrote this novella in a bout of homesickness years before Maximum City. Of course, Mehta's homesickness was not for India per se, but for various cities across the globe he had lived in.

Often this homesickness makes Indian immigrants behave in a weird manner, says Mehta. They treat Prime Minister Narendra Modi as the "Gujarati Elvis" at Madison Square Garden, they back Donald Trump because he shares their "antipathy for Muslims", and afflict their hearts with "too much history".

Mehta tells his publisher Juggernaut, "...many of the NRIs are looking for order in a chaotic situation. Their idea of India is that it is a disorderly, corrupt place, and has too much democracy - what the country needs is a strongman like Modi, with his 56-inch chest.

"When he came to speak at Madison Square Garden, he was greeted like a rock star; Narendra Modi is the Gujarati Elvis. Although the majority of Indian-Americans have always voted Democrat, there's a small but growing section that likes Trump, because they share his antipathy for Muslims."

Asked if NRIs have faulty memories when it comes to their homeland like his protagonist Mahesh Desai does, Mehta says, "All human beings have faulty memories about their past, but exiles have particular memory issues. Particularly those who came to America - so many came here to forget their personal histories, to forge a new history.

"I see this with many of my fellow NRIs, like the way some of us avoid Indian food or you can walk into their homes and find nothing Indian in the decor, not even a little god somewhere. This erasure of memory, and the way memories keep invading your cocoon as you get older, is fertile ground for a fiction writer, or a memoirist. The most foreign country is childhood."

Immigration officer at Delhi airport asks Manipur girl: 'Pakka Indian Ho?'

A Perfect Life

Mahesh Desai is leading the perfect NRI life in the US. He is not a resident of Jackson Heights - which Mehta describes as a "kind of middle world between India and America" - in New York. But when he accidentally lands there one day, he demands answers. He wants to know his mother's name, he wants to know what his caste is, what his grandfather's profession was.

The information thrown at him - that his family sold human hair, skeleton and frogs and that his mother was Indira Gandhi - disgusts him. He leaves the Indian corner only to return a few minutes later. He repeats this procedure several times.

In between he picks up pearls of wisdom:

Everyone has history, but some people - especially exiles - have Too Much History. This is a condition far more serious than Bad History, which can hurt you temporarily, but is easily curable by a little Good History.

On a salesman's advice he decides to buy a remote with the usual play, repeat, forward and rewind buttons. When he fiddles with the remote the tiny electric shock arouses "some long-sleeping clump of memory cells..."

Grandfather had run away as a child and spent miserable nights on the hard pavement. Later in life, when he became rich, he filled up an entire room in his house with bedding. When guests came, he piled up their mattresses, made sure they had more than enough bedding, forced on them pillows, blankets, sheets, all the while saying, 'Do you want any more?' It was the same before going on a train trip.

The Narrative

We've read about NRI problems umpteen times, seen them become scripts for Bollywood films (Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge) - therefore the Indian immigrant's relationship with his place of birth is not new.

Remember Chitthi aayi hai -- the Pankaj Udhas song that became the anthem of all immigrants?

What makes Mehta's book different and delightful is the way he handles this rather cliched theme. He narrative is not linear, his truth has several dimensions. In his world, anything is possible. The possibility of possibilities are endless.

There's never a deja vu moment as one goes through the beautiful prose, the intelligence, the wit, the detailing page after page.

Sample this:

Mahesh would usually get up later, at eight, when the sun on the terrace could not be fended off any longer with an extra pillow. By that time the milkman had already come and gone and the vegetable seller would be wheeling along his cart in the little lane, crying 'Breeen - jaals. Brinjals and tomaaay - toes'.

Or this:

On their (his uncle with film starlet Nylex Nalini) wedding night, it was your mother who took the milk with almonds to your uncle so he would not fail his manhood. It was your mother who faced your grandmother's ire when the new bride, in her first foray into the kitchen, put margarine on the chapattis instead of pure ghee.

I don't know if Mehta ever experienced the pain of immigration, but if he did, I am certain he conquered it easily. That's why he is able to document the angst of immigrants so beautifully and with the detachment of an old sage who has been endowed with the collective wisdom of the Saptarishis - the seven great sages of ancient India.

Economics 'Trumps' bigotry: Donald Trump mocks Sikhs but loves India's growth story. Wait, what?

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)