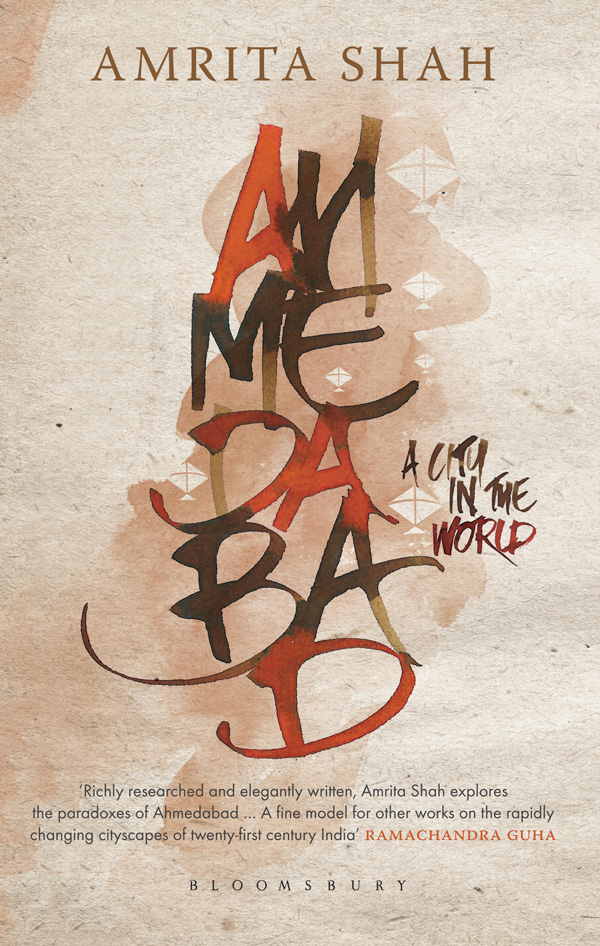

Amrita Shah's 'Ahmedabad' catalogues the human impact of the city's violent past and present

It's a city whose history has been shaped by violence - and yet been central to movements for peace.

This week, as members of the Patel community hit the streets of Ahmedabad in massive protests demanding OBC status, the peaceful face of the city was nowhere in view. Nine people lost their lives. Protests took on a fierce aggression. Cars and hospitals were set on fire, the army was called in, colleges and schools shut down and curfews put in place.

Against this background, Amrita Shah's provocative book, Ahmedabad - A City in the World, becomes even more intriguing as it delves into the human impact of decades of violence. What it also does - through rich narratives of ordinary but telling encounters with Ahmedabadis - is draw attention to the city's apathy towards, and tolerance of, public brutality.

In the first and perhaps most heartwarming chapter, she speaks to a displaced Muslim entrepreneur, Meraj and, through him, draws attention to the city's grudging acceptance of a constant fear of violence.

But the most relevant insight she lends, particularly in the context of the recent riots, is this: the underlying motivation in most episodes of rioting and murder - both to live, and perhaps to kill - is the resilient spirit of Gujarati enterprise.

Simply put, it's business.

I first met Meraj in early 2008, in one of the ghettos that have arisen on the outskirts of Ahmedabad city to contain the flotsam and jetsam of Muslims thrust out by waves of communal violence. The movement which started as a trickle in the early 1990s became a flood after 2002, when over a thousand Muslims died across Gujarat in a series of assaults that came to be known collectively by the year of their occurrence.(...)

I had met Salim, sullen and distrustful, a witness in a case involving the atrocities of '2002' in one of the distant bleak apartment blocks built by an Islamic charitable trust. I had been to Juhapura, Ahmedabad's largest Muslim ghetto, where alongside old, close-set hovels were tall arched entrances to new colonies for middle-class Muslims and, across the road, sprawling bungalows with the nameplates of bureaucrats and businessmen who had recently moved to the ghetto.

In the Muslim-dominated neighbourhood of Jamalpur in the old city, I was surprised to see a giant kite with a photograph of chief minister Narendra Modi of the Hindu chauvinist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) widely condemned for his partisan role in 2002. In one of the shops in the lane, all owned by Muslims, were regular-size white kites with the slogan 'modi is great-happy new year'. The owner, a burly man with henna in his hair, muttering 'it is better to eat than to die', admitted that the warmth towards their bete noire was strategic rather than real, and arising out of a fear of renewed attacks at the time of the state assembly elections that had just gone by. As we talked the mock irony in his tone gave way to a gloomy dissatisfaction with the openly anti-Muslim posturing of the state government.

'Write', he said, with a sudden flash of belligerence. 'Write my name! We all have to die some day!'(...)

And then there was Meraj. Of average height, sallow complexion, with short dark-brown hair and a neat moustache, he was the kind of guy that would melt in a crowd. But there was an eager warmth about him that made him instantly likeable.(...)

Meraj had grown up in the working-class neighbourhood of Asarwa-Chamanpura. His family had lived in a compound of municipal workers where his father owned a paan ka gulla (a paan shop). Meraj's childhood was the ordinary childhood of the lower-middle-class Ahmedabadi. He went to the local municipal school, played with his friends in the open square in front of the colony or in one of the houses, flew kites on the terraces, participated in ceremonial swordplay with his brother on Id.(...)

In his late teens he faced a number of obstacles, he said. Helping his father at the shop in the mornings meant missing classes. Then, an outbreak of communal violence in 1992-3 meant he had to stop going to college for six months because the route took him through tense Hindu-dominated neighbourhoods. Worse, his father, fearing an attack, had sent everything that was considered to be of value in the house, including his textbooks, to relatives for safekeeping. Meraj failed his second-year exams. 'Once the line is broken,' he said, 'it is very difficult to connect again.'

Like other young men of uncertain means in the city, though, he had taken the precaution of providing for a back up in the form of a trade skill. He had enrolled himself in an embroidery course near the Relief cinema on Ashram Road. There he had learnt 'plain' and 'fancy' embroidery and stitching. He had bought himself a machine and started doing piecework.

In 1994 he got married. The wedding was in Mehsana, 76 kilometres from Ahmedabad, where the bride's family lived; the feast was vegetarian out of deference to her Hindu neighbours. Meanwhile business was picking up. There was a great demand for embroidery and finishing on fabrics headed for the Gulf. Meraj did not deal directly with exports but took on orders from the Sindhi traders of Kalupur, Revdi Bazar and Hari Om Market. He would cycle across every few days to meet with his clients, hiring a rickshaw to bring back the raw material or the 'maal' as he called it.

As the orders mounted, he bought more machines and hired workers. His workshop bristled with reams of cotton, polyester and pashmina, saris and kaftans. The orders were getting so voluminous that he was thinking of buying a second-hand Maruti van. By then he had had three small children and a car would have been useful for family outings as well. But he hesitated. It was not his way to give in to momentary impulses.

His priority was to expand the business: if the money would be better spent on buying machinery and hiring workers, then comfort would take a back seat. It was the typically Ahmedabadi way, to suppress present gratification for future growth. Meraj was the quintessential Ahmedabadi entrepreneur, living not randomly but according to a sagacious plan for business expansion. 'I was always saving,' he says. 'Saving, saving, saving. I would take the cycle instead of the motorbike to save on petrol. I would sacrifice all the time just to put money back into the business.'

On February 28, 2002, a mob of Hindu militants had burst in and destroyed everything he owned: household conveniences, vehicles, machinery. 'Cha!' he exclaimed, 'Cha!' still incredulous, six years later, at the manner in which the rioters, with their wanton destructiveness, had rendered his pragmatism impractical and foolish. The cheer faded from his face, his eyes. (...)

I sensed that no list of damages, however comprehensive, could account for the feeling of betrayal and rankling injustice that rendered him temporarily incapable of speaking. Finally he muttered: 'I should have just enjoyed my money instead.'

The moment of truculence passed. He resumed his story. Sudden flight with his extended family and Muslim neighbours across the railway tracks behind his house, two years in transit between a refugee camp and relatives, and then he went back. 'My neighbours mobbed me,' he said, breaking into a smile, 'someone passed a five-hundred-rupee note from one side, someone from another. It was like I was the chief minister or something. I felt my house calling out to me. I felt so bad!' Meraj, his brother, their families and their father, again set up home in Asarwa-Chamanpura. On the face of it things seemed okay but in reality they were living in terror of a recurrence of '2002'. 'Every time something happened, like a bomb blast ... even if it was far away, it made us so anxious and frightened. We were always checking, fearful that the person away from home would not return.' Finally, tiring of the constant state of apprehension, they all decided to move to an emerging ghetto.

Meraj fidgeted. He crossed and uncrossed his arms, smiled shyly. 'I miss living among Hindus,' he said with a sudden beguiling ruefulness. (...)

'My friends ... the food ... all my neighbours, Hindu, Muslim, we were ... what can I say? It was just ... great!'

It was the first time, through the miasma of horror, callousness, opportunism and injustice that '2002' had come to represent that I had heard the thrum of love and longing; an elegiac strain that had not been mutilated by the need to serve a cause, or render the instant. 'Would you take me there?' I spoke without thinking. I did not expect him to agree but he said yes right away.

Excerpted with permission from Bloomsbury India. Ahmedabad - A City in the World, Rs 499.

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)