Reading between the lines: did Rajan say 'Make in India' was flawed?

RBI Governor Raghuram Rajan is worried that in the future, emerging markets won't be able to rely on multinational companies' need for cheap labour to spur economic activity. Reason? These companies will shift to using robots instead of human labour. Speaking at a programme last week, Rajan said, "Technologies such as 3D printing and the emergence of robots has shifted the focus away from whether jobs would get outsourced to Bengaluru to whether the robot in the next room would take jobs away".

Also read - Decline in global trade may lead to another jobless growth year for India

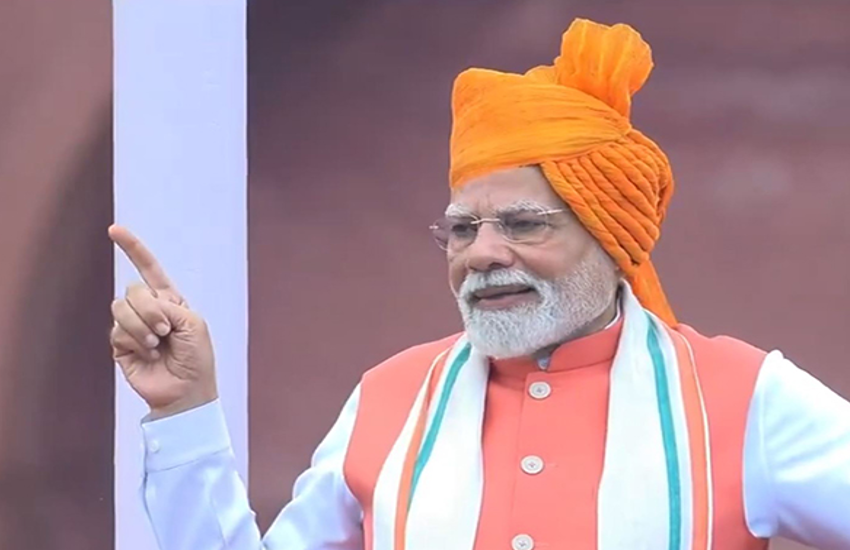

India needs to generate 10 million jobs every year until 2030 to cater to its growing young population. To this end, the Narendra Modi government has launched the "Make in India" mission, which seeks to generate 100 million jobs by 2022. And global manufacturing giants like Foxconn and Samsung General Electric have announced plans to invest in India under the mission.

Given this, should we take Rajan's concern with a pinch of salt?

Well, consider this. Just two weeks ago, a factory in China reduced its staff strength from 110,000 to 50,000, replacing the laid off workers with robots. The factory belonged to Foxconn, the world's largest contract manufacturing firm.

In India, 3,000 engineers are uncertain about their future at Wipro, which has decided to use Holmes, an artificial intelligence tool that can automate many projects. According to Mint, this tool will save the company nearly $46.5 million a year.

According to the Economic Times, Volkswagen India is using 123 robots at its Pune plant while Hyundai India, the subsidiary of the Korean carmaker, has 400 robots at its factory in Chennai. The entire body shop, most of the paint shop and parts of the final assembly line in these plants are automated now.

What do all these developments indicate?

Primarily, that 'Make in India' might never succeed in its core mission - to generate employment.

In 2015, India added about 1.35 lakh jobs while nearly one crore people entered the job market. This is a depressing figure, given that even at the height of global financial crisis in 2009, India had managed to generate no leas than 12.36 lakh new jobs.

So, should India be chasing global firms to generate jobs?

According to Arun Maira, a member of the erstwhile Planning Commission, "As robots are used in assembly lines, companies will no longer need Indian labour. That is why it's important to focus more on sectors such as food processing and agriculture. Those are the jobs that won't be affected by automation."

The context for Maira's point is that the Indian government is going out of its way to invite companies in the electronic manufacturing sector to set up shop here.

Recently, Niti Ayog was reported to have floated the idea of giving a 10-year tax holiday to companies in the consumer electronics sector to invite them to invest in India. But will giving tax breaks to such companies help the Indian economy in the long run?

Tax holidays cost a government significant revenue, which could have been used to fund public welfare programmes. That is why tax breaks should be offered only if the revenue loss is compensated by the generation of a large number of jobs. India, for example, promoted the domestic IT sector through a tax holiday that lasted nearly two decades.

But if companies like Foxconn are going to use robots to make products that would be consumed in India and abroad, there would hardly be any benefit to the Indian government from subsiding its operations.

Ajay Kumar, a research associate at the Centre for Policy Research, says, "Sectors that can provide jobs to India's increasing working age population are garments, food products, leather, wood products, which are part of traditional manufacturing and use labour-intensive methods of production. The Foxconns and other IT and electronics companies will employ a very small part of India's workforce."

What's the condition of labour-intensive industries in India?

These industries are mostly part of the Small and Medium Enterprise sector, and are largely ignored in favour of largescale manufacturers. Still, as much as 40% of India's 50 million workforce is currently employed in the SME sector.

Ideally, every policy paper that discusses manufacturing and job creation in this country must focus on SMEs. But the government's decisions in the past have usually gone against the sector.

In November 2015, for instance, the NDA government diluted FDI norms in single-brand retail in the hope of giving a fillip to "Make in India". It waived 30% domestic sourcing requirement "in certain high technology segments" where "it's not possible for a retail entity to comply with the sourcing norms".

This meant that a "high-tech" company selling a product in India was no longer required to source 30% of its component parts locally. It could just import the product and sell it here.

Gautam Mody, General Secretary of New Trade Union Initiative, criticises the relaxation of norms to attract FDI. "No society has grown with the help of repeated inter-generational imports of technology. Indian manufacturing derives largely from imported technology. Make in India will not work unless it is focused on 'making for India' by addressing the creation of indigenous technologies rather than depending on imported technology with only cheap labour to offer in return."

Companies from the developed world have maintained their dominance with the help of technology that has never been passed on to Indians. These firms made huge profits by selling their products in India in return for creating just a few thousand jobs. Now, even these jobs are likely to be made redundant by robots.

Now is the time for the Modi government to reconsider whether it should lay out the red carpet for the likes of Foxconn, or instead focus on promoting domestic labour-intensive industries, however unglamorous they may.

More in Catch - NITI Aayog proposes tax holiday for electronics manufacturers. Will it work?

Raghuram Rajan is an asset. Govt must stop hating him & take his advice

First published: 13 June 2016, 11:48 IST

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)