After Hindi cinema had sunk into a morass of mindless violence and choreographed candyfloss in the 1990s, Hansal Mehta had emerged as one of the few rays of hope. His Chhal (2002) was one of the few films, outside Ram Gopal Verma's Factory and prodigies, that strived high on a limited budget.

In the current decade, Mehta has achieved a wider audience, teaming up regularly with Rajkumar Rao (Shahid, City Lights, Aligarh). Directors depending on one lead actor is nothing new and Mehta's trust has paid off in Omerta.

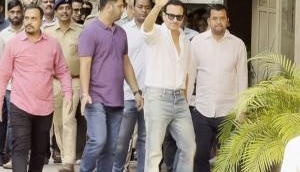

Rao, whose Newton last year was India's entry for the Oscars, has delivered yet another solid performance, carrying the entire film on his shoulders. He is there everywhere, all over in this near-biopic of Ahmed Omar Saeed Sheikh, better known by the Indian media as terrorist Omar Sheikh – lodged in a Karachi jail since 2014.

From the first to the last, few sequences are such where Rao isn't present. Those few too are mostly about him. Such an author-backed role is a dream for every actor but also a test of mettle for most. Rao passes that like he has several times in the past. He shines through as an intelligent, England-bred Pakistani boy, who is moved by the horror of Bosnia, trains with fundamentalists in Af-Pak as the 'War of Civilisations' was taking off and gradually grows to be a cunning, motivating terror leader.

In the process, he holds close-ups with elan, does different accents fluently and generally comes across as comfortable in the skin of the terrorist who kidnapped foreign tourists in Delhi – one of those whom former defence minister Jaswant Singh had to escort to Kandahar and set free in lieu of the hijacked passengers of IC 814 in 1999.

After that incident, Omar Sheikh's stature as a terrorist only increased: he could have been a funder of 9/11 accused Mohammed Atta and a year later, in 2002, he was sentenced to death for the kidnap and murder of Wall Street Journal's Daniel Pearl.

If you make plot points of these, Mehta has achieved a good docu-feature, banking on Rao's prowess to hold it all together. Everything else, except the painstakingly good detailing – is minimalistic. The camera sticks to a particular tonality of bluish grey with some occasional British sunshine as breaks from the world of terror and scheming. Among the other actors, Rajesh Tailang (General Mahmood of Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence) and Keval Arora (as Omar's father Saeed Sheikh), provide good support.

But after all this, Omerta underwhelms. Perhaps my expectation was higher from Mehta, but the feeling of 'a wanting' is what this film left behind. It's probably the way Mehta and Mukul Dev has framed the story – very tight (doff of the hat to Aditya Warrior for the 96-minute cut) and sparing. Too sparing?

Stills of Bosnian horror make the '90s come real, grabs of the Twin Tower and President Bush reminds of that fateful day; and then leaves you asking for more: Who was Omar? Who was he growing up? Who was he before being a student of the London School of Economics? Who was he before he came across those ghastly pictures of tortured Muslims? Who were the others who aligned with him, fought him, revered him and despised him? Which was that world? The '90s are so far away nowadays. So many would not know how it used to feel like a different world.

It's unfair to expect Mehta to know all answers, but perhaps the writer duo could have created a few more poignant moments. Omerta is a film true to its intent, which will benefit many by its record-keeping. But yes, that feeling of wanting to know more and have more cinematic moments lingers.

Rating: 3.5/5

First published: 4 May 2018, 14:39 IST

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)