MGNREGA@10: In Banda, a job card can be the difference between life and death

The anniversary

- MGNREGA has completed 10 years on 2 February. Has the Act worked?

- Catch visits Banda in UP, one of the first districts where MGNREGA was launched

The evaluation

- Many farmers have benefitted from MGNREGA especially in times of drought and distress

- But there are many others who didn\'t get work because of corruption and mismanagement

More in the story

- Did MGNREGA make any difference to the lives of the people in Banda?

- Why were certain people left out?

- How caste trumped MGNREGA

Ten years ago, on this day, the world's largest public works programme was born. On 2 February, 2006, The National Rural Employment Guarantee Act was launched with a mammoth goal: to ensure every family below poverty line gets 100 days of paid work a year. It was later renamed as the the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS)

The scheme has spent a budget of 3,13,844.55 crore till date. There are many milestones to celebrate: wages have gone up 81% since with most states paying between Rs 122 and Rs 191 per day. Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes account for 23% and 17% of the total man days. And the programme has fostered excellent gender equality with women accounting for 57% of the workforce.

Also read - 5 reasons why MGNREGA was the best thing to happen in the last 10 years

But the MGNREGS was never conceptualised as a scheme that a family could depend upon to earn a living as many mistake it to be. 100 days of work for a household, in Uttar Pradesh, for instance, would guarantee only 16,100 rupees a year. The paltry sum is only meant to get by during a lean farm season when it's hard to make ends meet or, as former Rural Development minister JaIram Ramesh called it, where there is a need for "distress employment". But what happens when it becomes your main source of income?

Catch visited Banda in Uttar Pradesh - one of the 200 districts that saw the first phase of this scheme rolled out in 2006 - to get a ground level reality check of the scheme's impact. Banda is situated in the drought-affected Bundelkhand region, possibly the worst place to be a farmer and home to India's lowest human development indicators. In Banda, we found that having a MGNREGS job card can often make a difference between being driven to suicide and choosing to live.

A caste battle hardly won

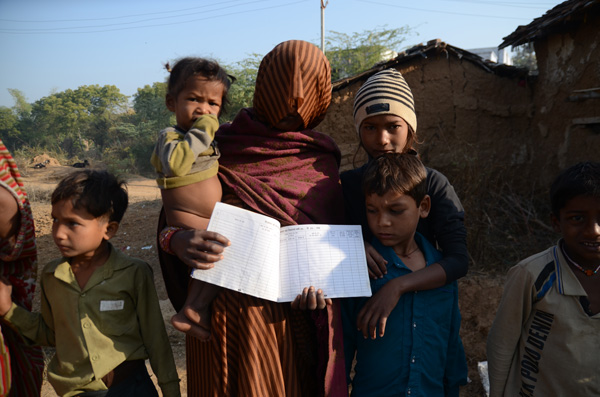

Nand Kishore's family stands with a blank job card. They are untouchables not just to the villagers but to the MGNREGS functionaries at the Gram Panchayat. Photo: Shriya Mohan/Catch News

The sun has barely risen and Rajkumar and his wife Sakuntala have set out for work from their home in Neeji Gaon. Their home is in Banda district's Naraini block. Today's work site is 3 kilometers away. They walk slowly, through forested bushy paths and through kaccha roads full of slush. It takes them an hour and half to reach. At the age of 50, Rajkumar looks older, greyer and darker than most of his clan.

His wife and him hold a job card just like the 25 other workers on the work site situated on vast swathes of arid farmland. Together they begin to plough the barren earth and level a patch under the watchful eyes of an MGNREGS supervisor.

Rajkumar and his wife belong to the Chamaar caste which is a Scheduled Caste. The caste draws its name from the word chamda, meaning skin, and refers to those who used to peel the skin off animals to make leather or burn dead people and animals. A Chamaar is an untouchable. To the upper caste, his mere shadow pollutes.

Rajkumar & Sakuntala have fought hard to be given work under MGNREGA and be treated equally. Photo: Shriya Mohan/ Catch News

When the scheme started in 2006, the couple got a job card just like everybody else but they were never given work. When all the members of their caste were also denied work they figured that it was because the villagers refused to touch the same soil as them, let alone work together.

In some years Rajkumar joined Banda's Vidya Dham Samiti, a rights based local NGO backed by Action Aid and became a crusader against caste based discrimination in MGNREGS.

"Today I'm like a permanent employee. They have to give me work every day," says Rajkumar, proudly showing the 124 days of work recorded on his job card. Due to Bundelkhand's severe drought the Centre raised the number of work days under MGNREGS from 100 to 150.

Wages have gone up 81%. SCs account for 23% and STs 17% of the employment under MGNREGA

"Most people like to take up MGNREGS work when it is within 500 meters of their residence. There are few like Rajkumar who land up wherever there is work. If the community has a problem working with a certain caste, we try to give them a job elsewhere," says Shiv Kumar Rajput, carefully. Rajput is the Gram Yojana Sevak, or the MGNREGS supervisor.

But Banda's SCs have a different story to tell.

At Bhagawan Deen's home lunch is rotis made of atta mixed with crushed wheat husk. Photo: Shriya Mohan/Catch News

In Gudha Kala village, 45 year old Nand Kishore lives with his wife and 6 children in a corner home. Kishore belongs to the Jamadaar caste, sweepers within the SC community. Showing an entirely blank job card he says that after he gathered the courage to walk up to the gram panchayat asking for a job and was turned down some years ago, he hasn't bothered checking since. "What's the point? I am barely allowed to sit on a chair outside my own home when an upper caste passes by, how will they let me work with others on a work site?" says Kishore.

Kishore and the 10 other SC families living in the neighbourhood are still forced to take a separate narrow path that trails the outskirts of the village, behind people's homes, so that there is least human contact with other castes when they move. It means that if the hand-pump in their locality breaks, they remain thirsty until it's fixed.

The programme has fostered excellent gender equality with women accounting for 57% of the workforce

Kishore says, however, that there has been an improvement since previous years. "Earlier I would get beaten up if my shadow fell on any upper caste person. Today perhaps not," he says hopeful that one day things will change enough for him to get work with his job card. For now, Kishore lives hand to mouth, feeding his family one meal a day. The family weaves bamboo baskets for a living and hardly manage to scrape through.

On Saturdays his children and his mother go to the Gudha Hanuman mandir to beg alms. "We sit from morning till evening. We get laddoos and prasad to fill our stomachs and sometimes if we're lucky, 10 rupees to get by," says 65 year old Kasturia, Kishore's mother.

"10 years of MGNREGS have been a joke for the lower castes of Bundelkhand. They have not gained anything. We need to collectively work towards changing social mindsets before we can talk about a free and fair public works programme that helps the masses," says Raja Bhaiya, secretary of Vidya Dham Samiti.

Drought, loans and migration

Ram Sia & his wife work at Gudha's MGNREGS work site. During the drought, their job cards were their only lifeline. Photo: Shriya Mohan/Catch News

In the sookhi, as the villagers colloquially call the dry spell, families like Rajkumar helplessly watched their small farms wilt and their fields crack. "We had planted wheat and chana. But ours dried like everybody else's, with no rains. It really helped that we got the MGNREGS work. At least we didn't have to live on grass rotis like some," he says today.

But no amount of scraping through can prevent the onslaught of indebtedness.

Rajkumar has 2 sons and 3 daughters. His sons migrate every few months to work in Hyderabad and Surat. Some months ago he got one of his daughters married. Because his crops failed for the third time in the drought and he took a loan of Rs 70,000 at an interest rate of 5% per month. He can hardly repay without taking another loan. He also has 2 more daughters to marry off. "This time I'm thinking of migrating. Let's see if I can find a job where my sons work," he says.

Upper castes don't allow me to sit on a chair, why will they let me get work, asks Kishore, a Dalit

For some, the MGNREGS has made them stay. Prem, 29, is the husband of a crippled woman and a father of 2 girls. While his girls go to school, his wife is studying her BA first year in a district level college. "She wants to finish her degree so that she's able to get a teaching job someday. So this year, when I got work under the MGNREGS, I decide to stay back," says Prem who used to spend more than half the year in Surat, where he polished diamonds for a living. His salary was Rs 10,000 a month.

"With my workdays here, hopefully I can manage somehow until my wife completes her education," he says.

"We've repeatedly seen that if people get the benefit of the MGNREGS, they are able to cut back on distress migration and their kids are better educated. Uprooting the kids repeatedly from a place means their schooling suffers," says Suresh with Vidya Dham Samiti.

Hunger and corruption of public works

Every Saturday, children from SC families come to beg at the Gudha Hanuman Mandir at Banda's Naraini block. The laddoo prasad fills their stomach & they earn 10 rupees to get by. Photo: Shriya Mohan/Catch News

Ask Bhagwan Deen when he had dal last and he gives out a hearty laugh. "About 3 years ago? Maybe 4," he says.

Deen, 50, is a father of seven children and was a regular MGNREGS daily wager until a few years ago. But 2 years ago, his job card was taken away by the former Sarpanch of Nuagawan village, Lala Ram Verma and it was never returned.

"That's what they do here, they confiscate our cards saying they'll take care of it and then we never see it again. Now we have a new Sarpanch who cannot help," says Deen.

The Vidya Dham Samiti in Banda has repeatedly filed RTIs to find out that job cards are misused to transfer payments for public works that never got constructed.

-

In 2014, a road that the gram panchayat claimed to have spent 4 lakh on connecting Gahabara to Bagen nadhi in Naraini block, never got constructed.

-

In 2013, in Piparahi panchayat a drain was shown to have been constructed by certain workers. But the Sarpanch had actually used a JCB machine to build it, which is against MGNREGA norms.

-

In Kolawal, another road budgeted at Rs 4 lakh was never made

-

In Baryari, a pond claimed to be dug by spending Rs 4 lakh, never existed.

"Across almost all gram panchayats in Bundelkhand, job cards are confiscated by corrupt Sarpanches and misused. It is also common to see job cards being made in the names of the family members of the Sarpanch to transfer the construction money so that it is all within the family," says Raja Bhaiya.

Raja Bhaiya found that of the 150 farmers who committed suicide in Banda district in the last ten months, only 30 of them had work issued to them in their job cards. Photo: Shriya Mohan/ Catch News

If MGNREGS has failed in Bundelkhand it is because of an utter vacuum of community participation with no village level micro plans being prepared to ensure that work continues to be provided to those who need it. A social audit process, technically a due diligence part of the Act would help check corruption and ensure more transparency, making sure that Deen's card is given back to him and the payment recorded is actually received by him. Sadly, there is nobody to monitor.

Back at Deen's house the menu is coarse rotis made of atta mixed with crushed wheat husk. The cooked rice grains are so broken that they look like the left overs from rice mills. To go with these is boiled leaves of chickpeas plants and salt for taste.

Banda's families are constantly innovating with how to add volume to food, cook it with less ingredients and consume even lesser. Using chilies are one way of making the food so spicy that it kills your hunger. Other methods include adding grass or hay or leaves of fruit trees to the food you consume so that it fills you. Grass rotis invented by the residents of Sulkhan Kapuruva became famous for exactly this reason. "Any green is nutritious right?" they ask.

The Act between life and death

Last April, Sohan Lal and Raja Bai were about to get their granddaughter married. Lal who was 70 then, had promised some money to the groom making a quick calculation of what his crops would fetch.

It had rained unseasonably that night. The next morning, he set out to check on his 3/4th bigha of land where he had sown wheat. He stood at his fields, dumfounded at the sight of the damaged wilted crops. He returned home in a state of shock not speaking a word and when he lay down to rest, he never woke up.

Lal's family says what killed him was the shock of never being able to give the groom the promised money. What killed him was the loss of face.

Lal had no MGNREGS card. So when he died, the UP government gave his family no compensation for crop damage and his wife no widow pension. Raja Bai sits desolate looking in a house that feels haunted to her. Their granddaughter is yet to be married. That life is in limbo needs no explanation.

Although Lal's case isn't suicide, Vidya Dham Samiti believes that the farmers of Bundelkhand are under tremendous duress.

MGNREGS work helped. At least we didn't have to live on grass rotis, says farmer Rajkumar

According to a detailed account of farmer suicides the Samiti put together, Banda district alone has seen 150 farmer suicides in the last 10 months. The important part is this: 125 of these were job card holders but only 30 of them had about 25-40 workdays given to their households. The rest held blank job cards, not having worked a single day in the scheme since its inception.

"The MGNREGS gives a ray of hope to a depressed farmer. It is only when a farmer feels he has no lifelines left, does he take the plunge. The scheme, if implemented well, can be that life saver in Bundelkhand," says Raja Bhaiya.

As MGNREGS completes 10 years and the government boasts of a 5 year high in work days, it should look Bundelkhand in the eye without turning away.

More in Catch -

Terror attack: 50% of India is reeling from drought. Here's the impact at a glance

Govt has failed drought victims by starving MGNREGA of funds

First published: 2 February 2016, 10:24 IST

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)