In the footballing circles of the country, the hottest topic of discussion, for quite some time, has been the long-mooted restructuring of the Indian Super League, the I-League and other domestic tournaments.

On May 17, 2016, the All India Football Federation (AIFF), in presence of representatives from IMG-Reliance, ISL and I-League clubs, presented a first draft for the restructuring of the Indian football leagues.

Whether the structure is widely accepted, and how the implementation on ground ultimately happens, remains to be seen.

The single biggest factor for professional football in India, however, is going to be financial sustainability. Football is a serious business, and every businessman working in this industry would want the money going out to be earned back sooner than later.

Founded in 2007 I-League is the official league of the country, mandated by AFC and FIFA. Indian Super League, meanwhile, has captured the imagination of the football fans in India. It has become one of the highest attended leagues across the world, with the 2nd season of ISL seeing an average attendance of 26,376.

The ISL doesn't yet have the official league status, but those days aren't far away now. From a sporting point of view, more players need to be professionally playing the sport and get a longer sustained league to play in.

Hence, it is imperative that the leagues in India last longer and accommodate more teams. This is something upon which there is an agreement from across the spectrum of stakeholders.

There have been numerous talks around the footballing circles as to what shape, size and form the leagues in India will eventually take. However, the idea that it will be a simple process is only wishful thinking.

Not because putting fragmented pieces of elite football is a tough task, but because, at the heart of this complexity of bringing the leagues together is a fairly straightforward problem that the sport of football across the world is facing: financial sustainability.

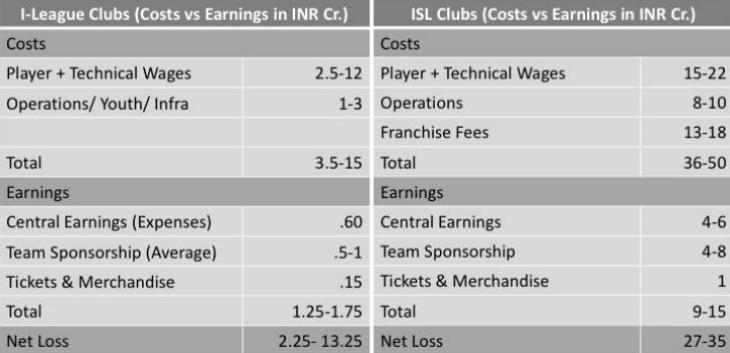

Investing into the sport is one aspect; ensuring that the league runs sustainably, thereby generating revenue for all stake holders, is another. The difference in average seasonal budgets between ISL and I-League sides is huge, which means the task for teams doing well in the I-League possibly going up to ISL is not going to be an easy task. The criteria for playing in the ISL for the times to come, rests on the financial capability of the clubs.

To put things into perspective, annual budgets of I-League clubs range from Rs. 3 crore (445,000 USD) to Rs. 15 crore (2.2 million USD), while those of ISL clubs range from Rs. 33 crore (4.89 million USD) to as high as Rs. 50 crore (7.4 million USD). With the league duration increasing in ISL, controlling these costs, though not impossible, will be tough. In the current scenario, recovery of this investment is a slightly tough proposition.

In the modern game, football clubs can't be money losing entities, though a huge majority of the clubs across the world might be doing exactly that. FIFA and continental federations are putting great emphasis on streamlined structures and strict financial control, as the business of passion, that football is, borders financial instability.

To understand the enormous task on hand for the AIFF, it will be a good idea to take a step back and have a close look at the current stakeholders in the Indian footballing ecosystem. It is critical to understand the roles they play, the stakes they have and their expectations from the system.

For a healthy and buoyant footballing system, it is important that these stakeholders work together, efficiently, in a financially stable environment, which in turn will ensure football supporters, and even more importantly, football players can be nurtured and taken care of.

There are 6 key stakeholders in the Indian domestic game at present. These are the All India Football Federation, IMG-Reliance, Broadcasters (Star Sports, in particular), Indian Super League clubs, I-League clubs, and most importantly, the players.

Here is a rough sketch of how the current scenario is shaping up for each of these stakeholders, as professional football in India enters its most exciting and critical phase:

1. All Indian Football Federation (AIFF)

AIFF is the governing body for football in India. The AIFF has a 15-year agreement with IMG Reliance for the commercial rights to Indian Football. The agreement is reportedly worth Rs. 700 crore (104.5 million USD). The current yearly agreement, into its sixth year, should be in the region of Rs. 50 crore (7.4 million USD) a year.

This is a very good revenue number for a non-cricket federation in the country. This revenue is currently being utilized to fund the development activities, I-League, Federation Cup, National Team operations, staff salaries, and crucially, train the Indian U17 team for the 2017 U17 World Cup.

AIFF currently is in a comfortable position financially. This revenue for AIFF also brings in safety and comfort to various football activities running across India.

2. IMG-Reliance

IMG-R, the joint venture between IMG and Reliance, is today the biggest sports management company in India, and has vast experience in managing sports properties. Having bought rights for football in India, they are chief promoters of Indian Super League, as well as right-holders of all other football properties in the country.

IMG-R will be spending a reported average sum of around Rs. 50 crore a year for the rights to football in India. Also, as part of Football Development Sports Pvt. Ltd (the subsidiary body that runs ISL), they can be assumed to be spending another Rs. 50-75 crore for event holding, management and salaries for the league.

This is an assumed number used here for an argument and can vary quite a bit from the stated number. A rough number of Rs. 100-125 crore/year (14.9-18.7 million USD) is currently tough to recover in the Indian Football market. Reliance the company is known for it's long term vision in supporting sport in the country and is backed by ambitious owners.

They would have a long term vision of turning the league, and football in India in general, into a thriving property. An average franchise fee of Rs. 13-14 crore (approx. 2 million USD) for each one of the franchises in the ISL would have seen them add around Rs. 120 crore (18 million USD) into their kitty.

However, with the clubs incurring high expenses in the first two seasons of the league, the Rs. 13 crore/year is proving to be a tough inclusion in their payment bills. A well-performing domestic football industry in India can ensure the promoters can actively work towards recovering their effort and investment in the times to come.

As is the case with any organization, IMG-R would have to justify spending the kind of money they are currently investing on football in India. IMG-R has been ambitious, and ISL has seen great success so far. However, apart from the biggest boon of fans getting attached to the sport, some of the other goals will have to wait for a longer period of time.

3. Broadcasters

Star Sports broadcasts the Indian Super League and is one of the partners in the ownership company of the ISL too. Ten Sports has been broadcasting the I-League. One of the biggest reasons for the success that the ISL has found with fans and followers is due to the effort and the marketing might that the Star Group has put behind the league.

Broadcasting revenue is today the single largest revenue contributor to leagues and in turn clubs across the world. It could vary between 40-60 percent of total revenues by the league/club in most countries. Since Star Sports has ownership stake in the ISL, the league and clubs are not entitled to broadcasting fee share yet.

Star Group is heavily invested in the property, both in terms of the cost and channel airtime, which may not be returning them the investments at present. They, however, have the content and broadcasting rights, which is also being pushed on their regional channels and seeing great traction.

4. Indian Super League

From an operations and marketing point of view, the Indian Super League has had a lot of positives. TV broadcast and event management is of a world class quality, which makes the football look attractive to fans, live and on TV.

Stadium attendances are today the amongst the best four in the world. Although not all of these are ticket buying fans, a culture of consistent football in-stadia viewing is in process. Organisation of the league is world class, and match-day organisation can be compared to some of the world's best football leagues.

Both the clubs as well league organisers have put in quite an effort to create an event of this magnitude, something that has not been previously seen in India. Overall, the league provides great entertainment value, and for football fans, this is a huge plus.

There are a few pain points too which ISL would eventually want to iron out. A two-and-a-half month league doesn't go well with conventional footballing culture, and counter-productive to the development of the game in the country. For a cricket loving nation that is now used to IPL, it may be a good way to introduce them to the sport.

However, a significant number of Indian fans consume European football, and would ideally want formats closer to those. A longer duration of ISL has already been proposed from the 2017/18 season.

Players in ISL are currently housed in hotels, which turns out to be quite expensive for the clubs. Costs for various franchises, in this regard, can start at something like Rs. 1.5 crore (220,000 USD) going all the way to Rs. 4 crore (600,000 USD) for some cities.

Moreover, ISL games come thick and fast, with a game each day, something that fans are not used to in football. This not only affects the standard of play, but also causes fatigue among both audiences and players.

As far as finances are concerned, each franchise in the ISL has a minimum commitment of almost Rs. 30 crore a season (4.4 million USD). Player wages for the third season of ISL are now fixed with a salary cap at Rs. 18 crore (2.7 million USD), excluding designated player salaries.

The first year saw no salary cap and the second season had a salary cap of Rs. 22 crore (3.2 million USD), including wages of the marquee player (now termed as 'designated player'). On top of this, the wage requirement for the technical team could vary between Rs. 50 lakh to Rs. 2 crore.

Each franchise has to pay a minimum franchise fee of Rs. 13.2 crore, inclusive of taxes. On an average, operating costs per club are currently in the region of Rs. 10 crore. This would include stadium hiring, match day operations, refurbishment, grass-root initiatives, salaries, hotels, flights, marketing and various miscellaneous costs. Some clubs in the ISL could be paying more than that.

Revenues currently are in the range of an average of Rs. 6 crore, from team sponsorships. Certain clubs, in this case, are outliers, with them enjoying higher sponsorships. The 2015 Indian Super League season saw the ISL Commercial team clocking upwards of Rs. 100-120 crore (15-18 million USD) in central sponsorship numbers.

ISL today has 17 central sponsors. Hero is the lead sponsor entering the 3rd season of a 3 year deal. Some excellent brands such as Maruti Suzuki, Samsung, Flipkart, Puma, Amul, Muthoot, DHL, Volini, et al. are currently partnering the ISL.

This kind of sponsor interest in the sport of football hasn't been seen in India so far. This can be looked as another great success for the ISL. To me, the chances of this number going past Rs. 175-200 Cr (26-30 million USD) mark currently looks tough, though achievable in the long run.

The organisers have put forth a very ambitious Rs. 500 crore (74 million USD) commercial target for the ISL. It's a magical number indeed, but one that will be hard to achieve. ISL clubs would also make about Rs. 1 crore each, on average, through ticket sales.

Over the 2 seasons NorthEast United, FC Goa, ATK and Kerala Blasters have seen very good attendances, and have healthy proportions of paid tickets holders.

5. I-League

I-League and formerly the National Football League (NFL) currently is the officially recognised top-flight league of the country. The league, over the past few seasons, has seen some improved attendance numbers, the level of competition seems to be getting better and all clubs currently playing in the league have gained mandatory AFC and National club licenses.

The I-League has been home to some of the oldest clubs in world football, and enjoys patronage of the clubs who have invested in the league with almost no returns for a very long period of time. These clubs have been the incubation centre of football in India, and have managed to keep the sport alive in the country through some of its darkest times.

I-League teams currently spend anywhere between Rs. 3 crore (450,000 USD) to Rs. 15 crore (2.2 million USD) on wages and operations. The costs currently are majorly distributed to players and technical team wages (which forms around 65 percent of the total budget), and other functions such as salaries of staff, match day operations, youth team and infrastructure. The costs used to be 25-40 percent higher when the league was held for a longer period pre-2014.

The AIFF currently pays teams' travel and stay, which is in the range of Rs. 45 lakh (67,000 USD) a season . There are also allowances for match-day organisation from the AIFF for the home teams. The rights to the league are owned by IMG-R as part of the overall agreement with the AIFF.

There are no reported revenues earnt from broadcast deals or central sponsorship. Hero is currently the lead sponsor. The sponsorship value is not a reported sum. Clubs are entitled to ticket revenues and team sponsorship revenues.

While ticket sales are up and most venues see a relative growth in the number of tickets sold, the amounts are miniscule to the expenditure. The big two, East Bengal and Mohun Bagan, have had lucrative sponsorship deals with their part owner companies Kingfisher (United Breweries) and McDowells (United Spirits Limited).

Shillong Lajong, Bengaluru FC Mumbai FC and Aizawl FC also generate revenues mainly through ticket sales and sponsorship. However, no team in the league is currently close to the state of self-sufficiency from club operations.

6. Players

There are currently eight franchises in the ISL, with each one contracting 14 Indian players each, taking the total number of Indian footballers in the league to 112. These players together earn approximately Rs. 32 crore (4.8 million USD), with an average budget of around Rs. 4 crore (600,000 UD) per team.

Each ISL team has about 10 international players, including a marquee player. The total wage budgets on an average are approximately around Rs. 18 crore (2.7 million USD), with foreign players earning the majority of it.

With 9 teams currently playing in the I-League and a requirement of around 26 Indian players (and 4 foreigners) per team, it takes the number of players in the I-League to 234. With 10 2nd Division teams, with slightly smaller squad sizes, the number is around 200 players.

However many of the players who play in the ISL also play in the I-League and the 2nd Division League. The total pool of player would not exceed 500. This is a small pool of players for a country the size of India to nurture talent from.

Players have been paid well in the I-League and around the time ISL started. However with limited spots on offer, a majority of the players are picking up places for amounts not as attractive as the previous years. More than the incomes, the security of playing football on a professional contract, year-round, is a matter of concern for the player.

The two key goals

With the background to each one of the stakeholders being understood, it would be good to hypothetically look at the elite footballing ecosystem of India moving into a more stable, self-sufficient financial format. This should be done keeping in mind two key goals:

1. Football development in India

a. Long term planning of talent, for an 8-15 year horizon, at least. It is important that the footballing pyramid in India is lucrative at the top, with enough impetus given to the bottom (grassroots and youth football).

b. Sustained multi-tiered league pan-Indian league structure, coupled with zonal/local leagues. This will ensure we will have players engaged with clubs and playing longer periods of competitive football over probably 4-5, or even more tiers of professional football. This will require the top two tiers to have 16-20 teams each, and will have to be backed by regional, multi-state, district, youth and city-based leagues.

c. Youth structure: enough emphasis can't be laid on creating a sustainable youth structure. That, however, can only be done when the environment reflects vision, sustainability and comfort.

d. All of this will need joint efforts of clubs, AIFF and state federations, and more importantly, will need a buy in from state and local authorities, where implementation becomes critical.

2.Popularising the sport with football fans and other stakeholders

a. Interaction with team and management.

b. Good team performances.

c. Ease of stadium entry and exit.

d. Home grown players and heroes with good international names.

e. Activity and interaction with fans.

Achieving these goals

With that in mind, the league could be structured in the following manner:

1. 16 team league spread across India, to be increased to 20 over the next 4 years.

a. One team promoted from the 2nd Division.

b. New teams could be introduced to cover parts of India not currently represented.

2. Relegation immunity for a fixed period of time to all teams so the investment can be on building organisational capabilities and not just spending on players wages.

3. Plans to be firmed up for atleast 4-5 years and kept consistent with sign-ons from each of the teams competing in Divisions 1 and 2.

4. Nine-month league with season dates finalised for the next 4-5 years. A minimum period of leagues in states and cities to be defined.

5. Fixed player wages: Players wages for a 9-month league will not vary in proportion to the time from a 4-month league; hence, the fixed player wages can stay.

6. Housing : homes (contracted/non contracted).

7. Flights plus stay for only 18 players, plus officials while travelling for away games.

8. Match-day operations' cost, around 1.5 times of the current Indian Super League standards, to be borne by the home team. This is to limit costs incurred by the central organisers in having their event organisers at each match venue. Only guidelines and checks, and no investment, to be provided by the central committee for the clubs.

9. Match-day operations are a huge expense in the ISL; however, the levels match international standard. This has to be followed across the new league and teams have to sign up to deliver. It has to be a non-negotiable clause in the new sign ups.

Central sponsorship and broadcast fee

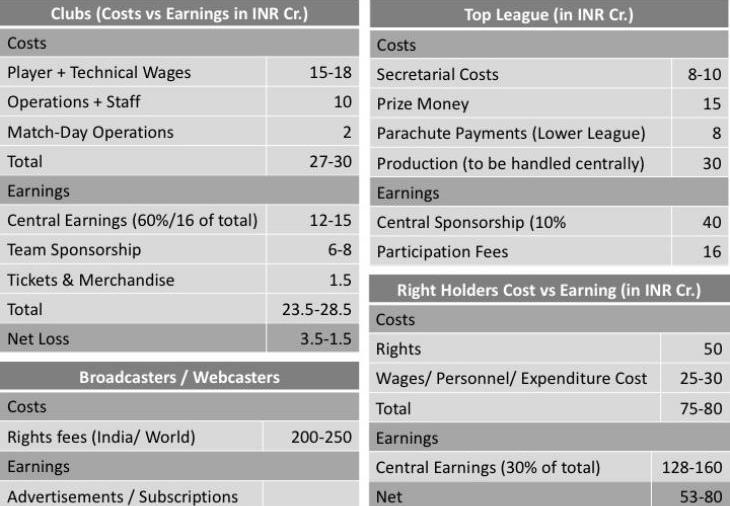

A broadcast deal with current levels of airtime and promotion by Star Sports is the most critical cog in the sustenance of a unified league. Any business model without broadcast revenues is bound to heavily tilt the investment burdens on owners.

As an example, in the Australian A-League, almost the entire player wage cap (2.2 million USD) is adjusted for by the broadcast deal with FOX sports (a reported 160 million USD for 4 years starting from 2013-14). The Football Federation of Australia is now gunning to compete with Rugby League (500 million USD/year) and Aussie rules football (445 million USD/year).

The unified league will need at-least a Rs. 200-250 crore (30-37 million USD) broadcast deal for the teams playing in the league, and the solidarity payments to the teams playing in the lower leagues. This is assuming that the central sponsorship deals will max out in the range of Rs. 150 -200 crore for a 5-7 year horizon.

A net total between Rs. 320-400 crore after accounting television production cost of Rs. 30 crore in a 40-60 ratio (40 percent to central committee and 60 percent to teams) for a 16-20 team league can give a share of Rs. 12-15 crore to the clubs.

It is imperative that the overall commercial numbers reach close to Rs. 400 crore for the planned football structure to sustain. It is a big ask for the broadcaster with contribution percentage, but with numbers in the region of Rs. 200-250 crore a year the league certainly has a strong shot at financial sustainability.

With Reliance's Jio platform also planning to take the country by storm, a huge chunk of broadcast could be taken off TV and exclusively to the web if partner company so wishes. The ambitious Jio project could offer a way out for the broadcast deal to be staggered heavily on TV.

Franchise fees

No franchise fees; instead, a higher share of revenues for the organisers. Currently, the IMGR-Star Sports Combine garner a 20 percent of the total revenues coming in centrally. This can now upped to 40 percent in case the broadcasting/webcasting rights are paid for.

With a complete kitty of around Rs. 400 crore, the organisers' share would rise to Rs. 120 crore a year, which can very well cover the costs and fees paid for the rights to football to the AIFF. Participation fee per club can be between Rs. 50 lakh to Rs. 1 crore to cover for secretariat costs for the central organising committee can be implemented.

Club Earnings

Team sponsorship for a 5-7 year horizon, especially for a 16-20 team league, can be looked at around Rs. 6-8 crore per year. Advertisers and sponsors will need further evidence of work done by the league and the teams, specifically for a longer duration of time, before team sponsorship numbers begin to grow.

Tickets and hospitality for a 9-month league with 15-19 home games can further garner about Rs. 1.5 crore, and a small, yet important, Rs. 20 lakh odd coming in from merchandise sale.

An arrangement of this nature would take care of interests of all stakeholders, with the clubs' income totalling close to Rs. 23-28 crore a year, as against expenditure ranging from Rs. 27-30 crore. Not all teams will be able to optimise their wage budgets.

Critically, right-holders have a revenue stream, and reduced expenditures should see their net expenditure, over a sustainable period of time, brought down. The critical cog, as stated earlier, will be Star and its investment in the sport in India.

The group has backed sports properties in India not just as broadcasters, but as organisers and co-owners. It is a known fact that broadcast revenues are an absolutely necessity for the unified league to move forward. However, for an organisation to justify spending more on a property they already hold ownership in, is a tough call.

Implementation of the entire restructured league, including the business model, and with multiple stakeholders on board, in a country of India's magnitude, will be another herculean task as well. But it is something which will define where India moves as a footballing nation. And hopefully, majority of the moves we make, from this point onward, are the right ones.

Disclaimer:Some of the financial figures mentioned in the article are approximations of the actual amounts, and may slightly differ from the latter.

First published: 25 May 2016, 6:54 IST

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)