Allison Joyce is an American photojournalist who got her start covering Hillary Clinton's 2008 presidential campaign. However, since then, the Boston-born photojournalist has spent the bulk of her time travelling the world to cover social issues and news.

One of her more recent projects took her to the refugee camps in Bangladesh. These camps are home to thousands of Rohingya refugees who languish in squalor, having been driven from their homes in Myanmar due to communal violence.

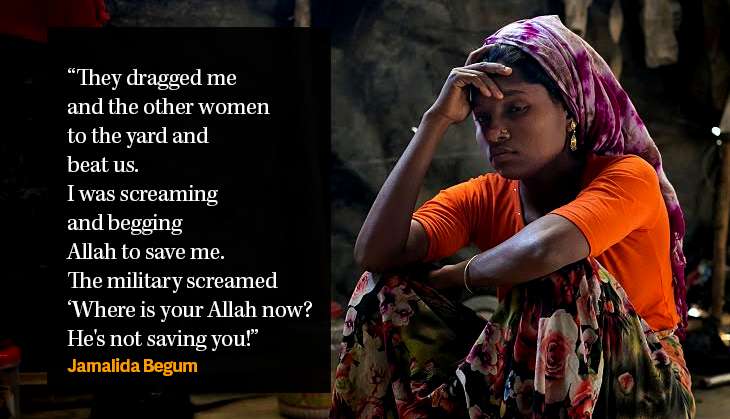

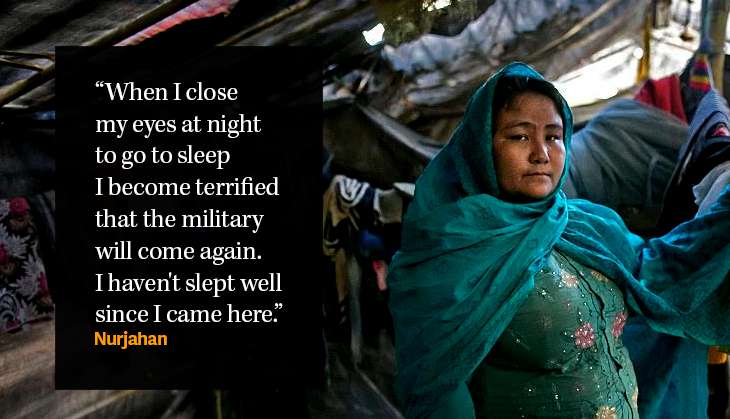

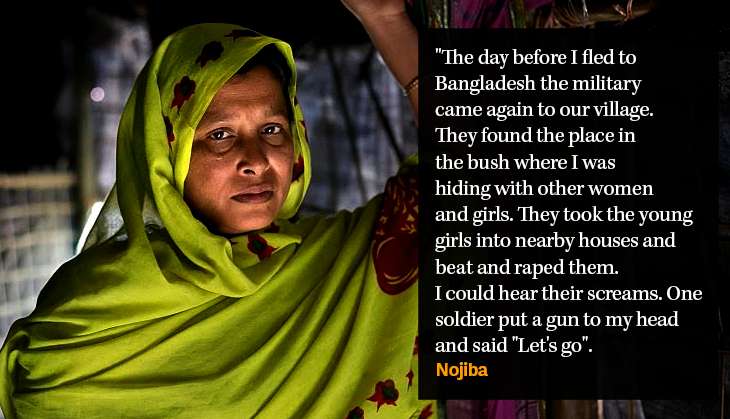

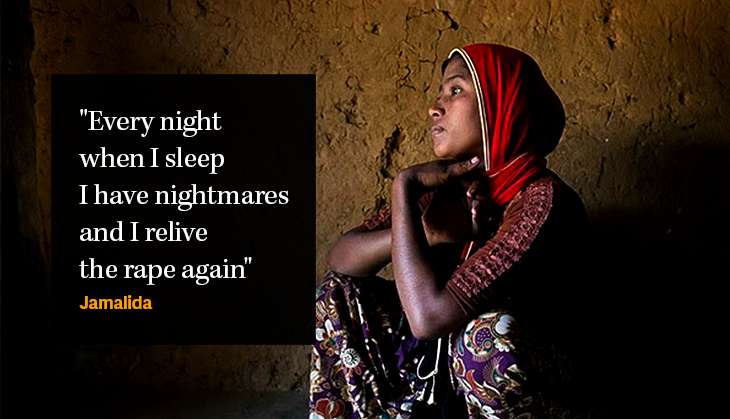

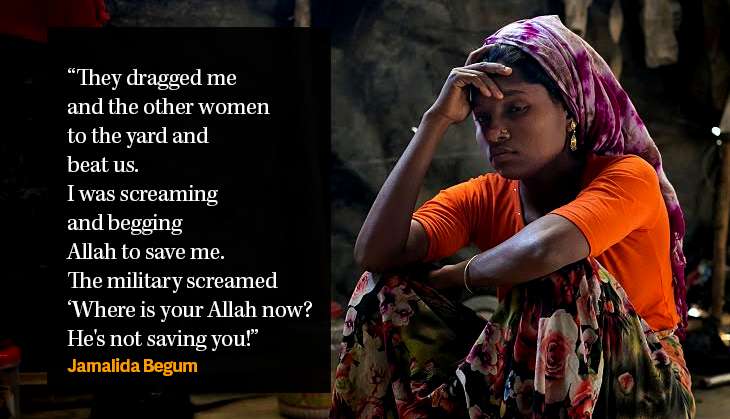

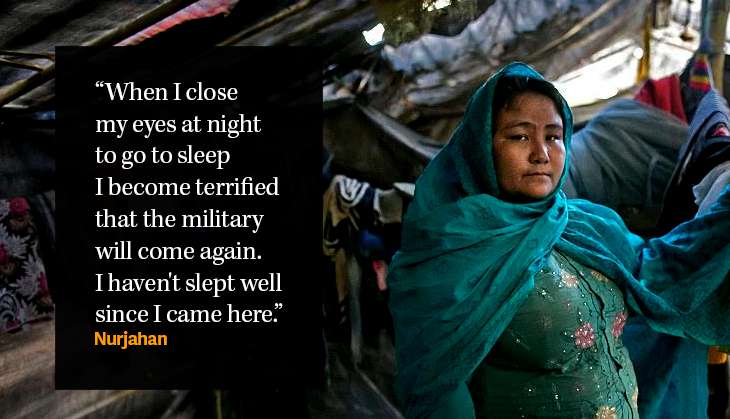

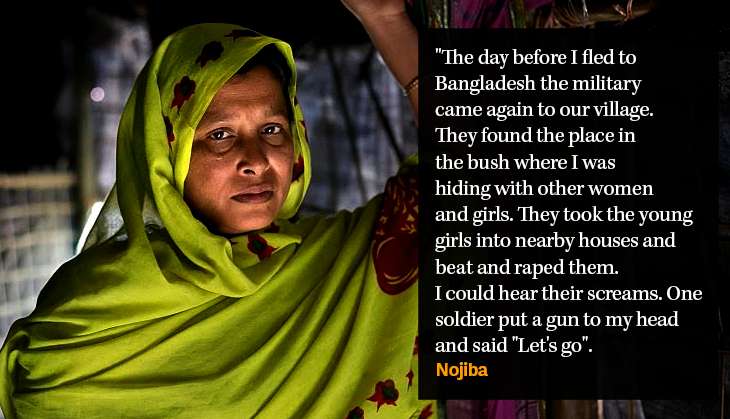

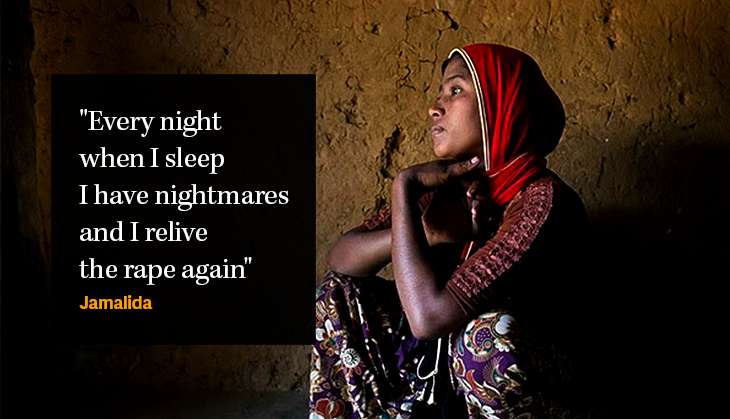

While she originally intended on a more general story, documenting the suffering of the Rohingyas in these camps, the tales of brutality against the Rohingya women made her alter her plans. The result was a photo series chronicling Rohingya women who'd been raped by Myanmar state forces.

Joyce's simple and sensitive treatment of the photos, coupled with the women's brutal testimonies resulted in a story that lingers in the memory. A distressing reminder of the atrocities being committed in the world at large.

Speaking to Catch, Joyce talked about how the story came about, her experiences with the refugees and the ongoing Rohingya crisis. These are the edited excerpts:

SQ: Did you go to the Rohingya camps with this particular angle in mind, or are these portraits of rape survivors an angle that started to emerge when you were doing a more general photo story? Is rape a common narrative among female Rohingya refugees?

AJ: I went to cover the story as a general hard news piece, taking photos of the crowded camps and new arrivals. I was so shocked though as I talked to the refugees, almost all of them mentioned the Myanmar military raping women and young girls in their villages.

One of the camp leaders in Balu Kali camp directed me over to a makeshift house, one afternoon, with refugees that had just arrived a day before and he, very loudly, in front of a crowd of people, said, "They were raped! Four of the women were raped!" It happened to so many women in many many villages, it's public knowledge.

SQ: How hard was it to find these women and how long did this series take? Did you face any obstacles to doing the piece? How were you able to get them to open up to you and share their stories?

AJ: I spent two days covering six survivors. I was lucky to work with a fantastic female fixer who knew of a few women who were open to telling their stories. There weren't many obstacles.

The Myanmar military severely limits the access of humanitarian groups and independent journalists into the conflict areas, so, in fact, many of the survivors seemed eager to share their stories.

SQ: Your treatment of the photos is very simple, there is no visible grittiness in any of them. Was this a conscious decision and why?

AJ: These refugees have been through horrors that most of us can't even conceive of; seeing their loved ones tortured before their eyes, fleeing from village to bush to village, hiding in ponds and rivers for days at a time, surviving by eating leaves. The only conscious decision I made is that I wanted to portray them with dignity.

SQ: The Myanmar government often denies reports of violence against the Rohingyas. Based on your interactions with the refugees, how dire would you say the situation is? What other horrors are they subjected to?

AJ: The situation is incredibly dire.There were new refugees fleeing into Bangladesh every single day that I was working in the camps. They had chilling stories to tell.

More than one described the Myanmar military attacking their villages and going into the midwife's home and shooting mothers with their newborn babies on sight, raping 8-year-old girls in front of their mothers, shooting and killing men at random and cutting their bodies into 4 pieces in front of the whole village.

It isn't stopping or slowing down, but this is nothing new. The Rohingya have been fleeing into Bangladesh for years and years. These new refugees are fleeing to camps like Kutapalong and moving into houses next to second generation Rohingya. These atrocities have been happening for a long time and the world sits by and watches. History will rightly judge us harshly for allowing this to happen unabated.

SQ: Tell us more about these refugee camps...

AJ: There are two kinds of camps, registered and unregistered. There are about 30,000 registered refugees in Bangladesh, and they receive support and aid from the government of Bangladesh and UNHCR. Their houses are well made and their streets are wide and tidy. They haves NGO-supported schools for their children.

Unregistered refugees, it's estimated that there are 5,00,000 in Bangladesh, receive nothing and their precarious status puts them at risk. They seldom approach the police to report crimes or visit hospitals, fearing that they will be discovered, arrested, and possibly returned. Their status leaves them with little options to earn a living, other than fishing, rickshaw pulling, or working as day labourers in fields, where they are often paid much less than their Bangladeshi co-workers.

Their camps are densely packed and incredibly crowded, with as many as 14 people sharing one makeshift house. There are many NGOs working hard to provide them with as much as they can, but the conditions and crowding leave them at risk of disease.

SQ: Is there some set up within the camps to provide counselling and support to these women?

AJ: Action contre la Faim and MSF, and possibly other NGOs, provide group as well as one on one counselling to women and children.

SQ: Do you feel this story has changed you in any way?

AJ: I wouldn't say that the story changed me in any way.But, as an American, now was an especially difficult time to be working on this issue. Every day we have to hear this disgusting, bigoted, anti-refugee, anti-Muslim rhetoric, and now new policy, from our president.

I wonder how any of these refugees that I photographed could possibly be any threat to people in my country? They had land, homes, jobs, cattle, family, love, and lives in their country before they were uprooted, and many of them told me all they wanted was safety and security in Myanmar so that they could go back.

No one chooses to flee across a river or dangerous borders from their homeland unless they are forced to. One woman told me "All I want is food, clothes, and peace and I will be happy." Deep down we are all the same and I'm so ashamed to be from a country whose leader is spewing hate towards these people.

Allison Joyce (Allison Joyce/Facebook)

First published: 2 February 2017, 8:24 IST

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)