Aadhaar & hunger: How ABBA may have made PDS more vulnerable

_92723_730x419-m.jpg)

Recently, there have been a spate of harrowing reports on how a mandatory Aadhaar for essential services like the Public Distribution System is leading to exclusion, even starvation deaths. A survey report says that as many as 11.2 lakh card holders may not have been able to buy their rations, where the government had made Aadhaar Based Biometric Authentication (ABBA) compulsory for availing the subsidised food grains.

A survey report says that as many as 11.2 lakh card holders may not have been able to buy their rations in places where the government has made Aadhaar-based biometric authentication compulsory for availing the subsidised food grains.

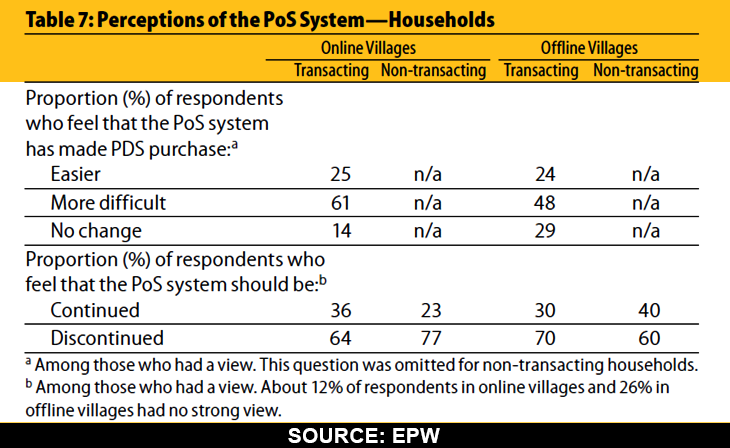

Even though the Jharkhand government made amends and claims that Aadhaar Based Biometric Authentication (ABBA) is no longer compulsory for availing PDS, findings of the field survey say that more than half of the people in Jharkhand want the system of compulsory biometric authentication for PDS to be discontinued.

The survey findings also suggest that corruption in the PDS may have, in fact, gone up. This flies in the face of claims made by the government and proponents of Aadhaar about how it is plugging leaks.

The Supreme Court will now take up the fate of the controversial identity project in January when a Constitutional Bench will hear a bunch of petitions, some of which have been pending for many years. In the interim, it has ordered that all the deadlines for mandatory linking of Aadhaar be extended to 31 March 2018.

The survey's findings

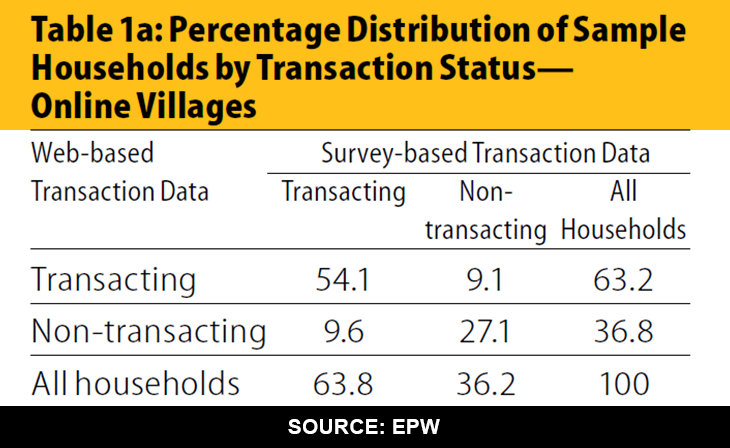

The field survey, which was carried out in June, throws up some startling figures. Only 3% of surveyed households in the villages, which have online Point of Sale machines for PDS transactions, used one time passwords - an option which is used once the biometric authentication fails - something which is not very uncommon in rural areas where both connectivity and other factors including failure of the machines to recognise biometrics are at play.

The survey data, which was published in a paper in Economic and Political Weekly, says that in Ranchi, where all PDS outlets worked online and then there was no exemption from biometric authentication, the transaction rates hovered around 80% between January and July except in June, when it fell to 59%.

Extrapolating from this data, the authors - economist Jean Dreze, Reetika Khera, Anmol Somanchi and Nazar Khalid - say the number of households who have not been able to get their rations could stand at 81,000 cardholders in Ranchi alone and a staggering 11.2 lakh cardholders in Jharkhand.

A random check on the Jharkhand government’s website of the Department of Food, Public Distribution and Consumer Affairs shows that in the Ramgarh block of Ramgarh district, transaction rates were as low as 46% for the month of November in the case of a dealer named Budiya Mandir Mahile Mandal.

In Khunti, another backward district, data for dealer Bandhna Pahan shows only a 13% transaction rate in November. The average transaction rate for 12 dealers who function online in Khunti block is a mere 56.7% for the month of November, which basically entails that about 43% of the people have not been able to avail their monthly PDS.

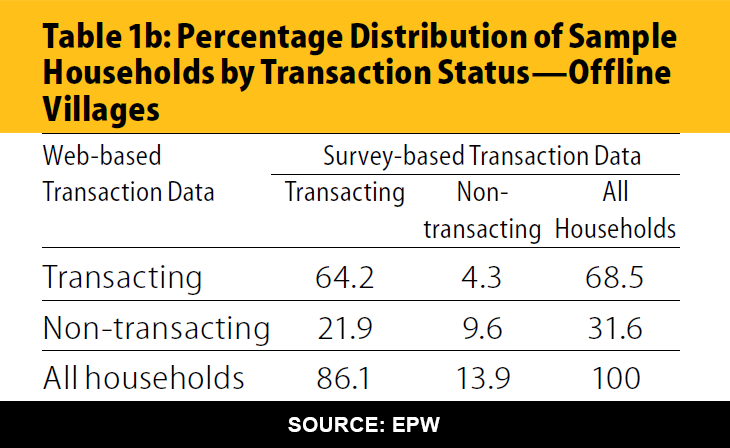

The survey, which was done months ago, meanwhile, had found that 21% of the households in online villages could not transact. The survey also found that transaction failures were five times as high in villages where PDS dealers were online than in those where the people could transact in an offline mode. The data claims that as many as half of the non-transacting households reported that they could not transact because of POS related issues.

The authors of the report say that ABBA bears a higher responsibility since only 10% “people reported problems with POS in villages where people had the option to transact offline".

The data also reveals how on an average, every household with PDS shops working online had to make a trip at least 1.5 times a month to get their monthly ration. Sometime this could entail a walk of a few kilometres, like this reporter had found on a field trip to Jharkhand earlier this year. This would mean one has to forego that day’s work - costing a day or half day's wage.

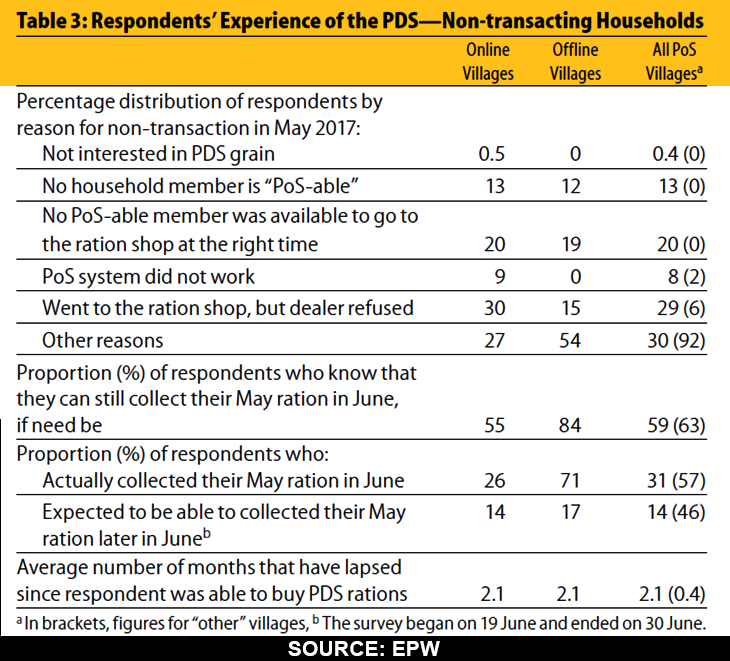

The survey's report says that as many as 20% of non-transacting households reported that the only POS-able member, that is the member who could be authenticated for availing the subsidised rations, was not available at the time of distribution.

The data says that there are as many as 7% households, mostly smaller ones, where there is no POS-able member at all. These households mostly have either elderly couples, or widows living alone. This reporter, for example, met several such elderly people who have not been able to transact either because their biometrics do not work or their Aadhaar numbers have not been seeded.

Meanwhile, households had an option to get the previous month’s ration the next month if the transaction failed. Yet, as the data says, only half the surveyed households in villages with online POS machines, knew if this option existed and a mere 6% reported buying the previous month's ration.

Under the National Food Security Act, Jharkhand has two categories of cardholders: priority and ‘Antyodaya’. While ‘priority households’ are entitled to 5 kilogram (kg) of foodgrain per person per month at a symbolic price of Rs 1 per Kg , the ones under Antyodaya, mainly the poorest of the poor, are entitled to 35 kg per month irrespective of family size.

Did ABBA lead to less leaks?

The survey shows that may not have been the case. ABBA may not be a protection against ‘katauti’, as quantity frauds are referred to. The data says that Purchase Entitlement Ratio remained static at 93% when it comes to pre-ABBA and post-ABBA survey reports.

The authors claim that ABBA may, in fact, have made PDS more vulnerable to corruption since transaction costs for the dealers have gone up which the commission has not changed. For example, distribution of food grains which would take just about a few days before POS was introduced, now takes on an average about 13 days every month because of problems of authentication in many villages.

What does the government say?

Saryu Rai, the cabinet minister in the state government who is in-charge of the department of food, public distribution and consumer affairs, says the government has done away with compulsory ABBA. “If some dealers are still doing it then it is a violation of the Supreme Court order,” Rai told Catch.

He says confusion prevailed after an order from the Chief Secretary of the state said ABBA was mandatory for availing PDS. “But I intervened and annulled that order,” Rai says, adding that the state government is still continuing the seeding of Aadhaar numbers with ration cards.

The Jharkhand government and Rai were forced to move after the starvation death of one Santoshi in Simdega in October.

It was then that Rai had passed an order cancelling instructions by the Chief Secretary . The new order entailed that beneficiaries could produce any approved identity document to avail the benefits of the PDS.

“We have also given directions that one day every month all those who do not have Aadhaar or any other document, but have a valid ration card, can come and take their rations,” Rai says. Activists in Jharkhand claim that no such things exists on the ground.

Meanwhile, as the authors say, ABBA seem to have been an exercise which only entailed “pain without any gain.”

The Supreme Court could take a cue from the Jharkhand experience.

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)