Jose Mourinho, Wayne Rooney, Rihanna ... and the lucrative world of image rights

During the recent negotiations over Jose Mourinho's appointment as Manchester United manager, it became apparent that, even though he left the club in December 2015, Chelsea Football Club Limited still owned Mourinho's most lucrative image rights. For commercial reasons it was imperative that these rights be licensed or transferred to Mourinho/Utd before his new contract could be finalised. Reportedly this knowledge came as a shock to Mourinho - which begs the question: what are these rights and how did Mourinho's former employer come to own his image in the first place?

The English High Court, in a 2010 case involving Wayne Rooney Proactive Sports Management Ltd v Wayne Rooney quoted the following description of the rights covering Rooney's image with approval:

Image Rights means the right for any commercial or promotional purpose to use the Player's name, nickname, slogan and signatures developed from time to time, image, likeness, voice, logos, get-ups, initials, team or squad number (as may be allocated to the Player from time to time), reputation, video or film portrayal, biographical information, graphical representation, electronic, animated or computer-generated representation and/or any other representation and/or right of association and/or any other right or quasi-right anywhere in the World ...

However, it is notable that technically the UK does not recognise an image right per se - a position which stands in contrast to the US, where the widely recognised "right of publicity" gives celebrities the right to control their image in a wide range of commercial activities, including endorsements. Instead, there are three key aspects of UK law that can be used to protect a well-known person's image: passing off, trade marks and contract law.

Troublesome t-shirts ...

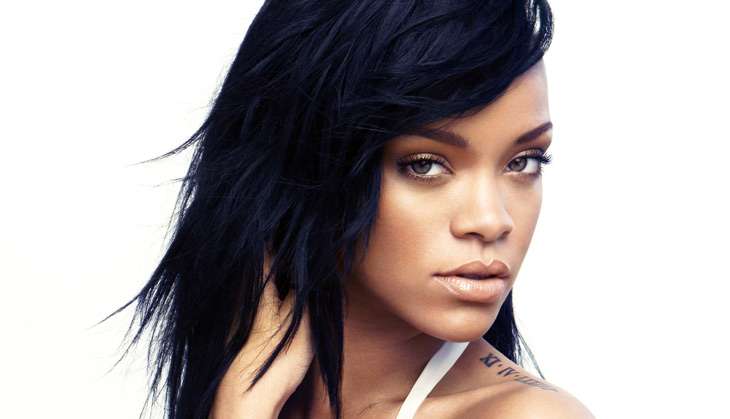

The law of passing off essentially concerns the prevention of false endorsement claims. A famous example that occurred recently in the UK is the dispute between the retail brand Topshop and the pop star Rihanna, which was adjudicated by the High Court in 2013 and the Court of Appeal in 2015.

Topshop sold a t-shirt embossed with Rihanna's image, and did so without Rihanna's permission. Rihanna sued. The case attracted a lot of interest in the legal world because prior to this dispute there was a general perception in the UK that the mere act of creating merchandise bearing a celebrity's image without the person's permission did not constitute infringement of the celebrity's rights.

The ruling of the High Court, later endorsed by the Court of Appeal, clarified that there are in fact circumstances when doing this will breach the law of passing off. Namely, Topshop's sale of the t-shirt amounted to a misrepresentation that Rihanna had endorsed the Topshop brand.

Given the nature of Rihanna's carefully cultivated personal image and brand - which included licensed fashion tie-ups, such as a previous one with Topshop - the impression on the customer would be that Rihanna had partnered with Topshop. For the court, this misrepresentation meant that Rihanna lost valuable control over, and goodwill associated with, her image.

Mugs and potpourri

The second way a celebrity can protect his or her image is via trade mark law. This proved to be crucial in the Mourinho negotiations. In 2005, well aware of their then-manager's growing popularity at the time, Chelsea registered the name "Jose Mourinho" as well as his signature under European trade mark law. According to the European Union Intellectual Property Office, the list of goods they can sell officially bearing his name includes after-shave, potpourris, and mugs.

There was nothing unusual in Chelsea doing this at the time - Mourinho was the club's manager and no doubt he acquiesced to their doing so as part of his contract. What is strange is that Mourinho and his management seemingly did not negotiate to take these rights with them on either occasion when his Chelsea contract was terminated, first in 2007 - which meant that his subsequent clubs Inter and Real Madrid would also have needed a licence from Chelsea - and again following poor results during his second stint in December 2015. This oversight is the reason Mourinho and Man Utd were forced to negotiate a deal last week with Chelsea in order to allow Man Utd to use his name and image, before Mourinho's official appointment as manager.

This brings to light another area of law important to image rights: contract law. Celebrities can agree to license their rights - i.e. trade marks - under contract to third parties, in order to gain endorsement or advertising revenue. A key example here is the Wayne Rooney case, which involved an eight-year contract signed by Wayne & Colleen Rooney very early in his football career, allowing his management company - Proactive - to exploit their image rights.

Binding contracts

When Rooney left his management company, Proactive, with around four years of the original contract still remaining, Proactive claimed they should still receive millions of pounds in commissions. However, luckily for the Rooneys, even though they had signed the long-term deal, the English High Court stated that it had been an unlawful "restraint of trade" for Proactive to tie Wayne Rooney to a deal longer than two years. For this reason, the amount Wayne & Colleen owed to Proactive was only £95,000 rather than the millions sought.

While the law covering image rights in the UK is untidy - requiring knowledge of passing off, trade marks and contract law - one thing that is abundantly clear after the Mourinho saga is that those in the public eye must be very careful whenever they sign contracts, and above all ensure that in signing they are not giving up the lucrative rights to their own image, for if they do they may later regret the embarrassing complications that follow.

![]()

Luke McDonagh, Lecturer in Law, City University London

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

First published: 1 June 2016, 15:48 IST

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)