BCCI presidential elections: Why is it still a cosy club of politicians?

- Shashank Manohar recently resigned as BCCI president, in order to take over as \'independent\' ICC chairman

- To choose his replacement as president, the Board will hold an election on Sunday, 22 May

- In this age of professionalism, why does the BCCI remain a cosy club of (mostly) politicians?

- Why do the politicians forget all their differences and close ranks to protect their turf, the BCCI?

- The secret behind the politicians\' mutual admiration society

- How sports administration the world over is not very different

They say sport mirrors the society in which it is played. Perhaps, we are now beginning to notice that sports administration resembles the country's political firmament, not least because even when you lose an election, you can be adjusted elsewhere as a 'winner', and because behind-the-scenes parleys lead to evolving scenarios.

Most recently, Goa's Chetan Desai, who lost the race to be BCCI joint secretary in March 2015, was made chairman of the Marketing Committee; Madhya Pradesh's Jyotiraditya Scindia and Uttar Pradesh's Rajeev Shukla, who also lost elections, were named to lead the BCCI Finance Committee and the lucrative Indian Premier League respectively.

Though the Supreme Court hanging the Lodha Committee report over BCCI like the proverbial sword of Damocles, the Board is readying itself for another stint at the merry-go-round, with its ensuing presidential election slated for 22 May.

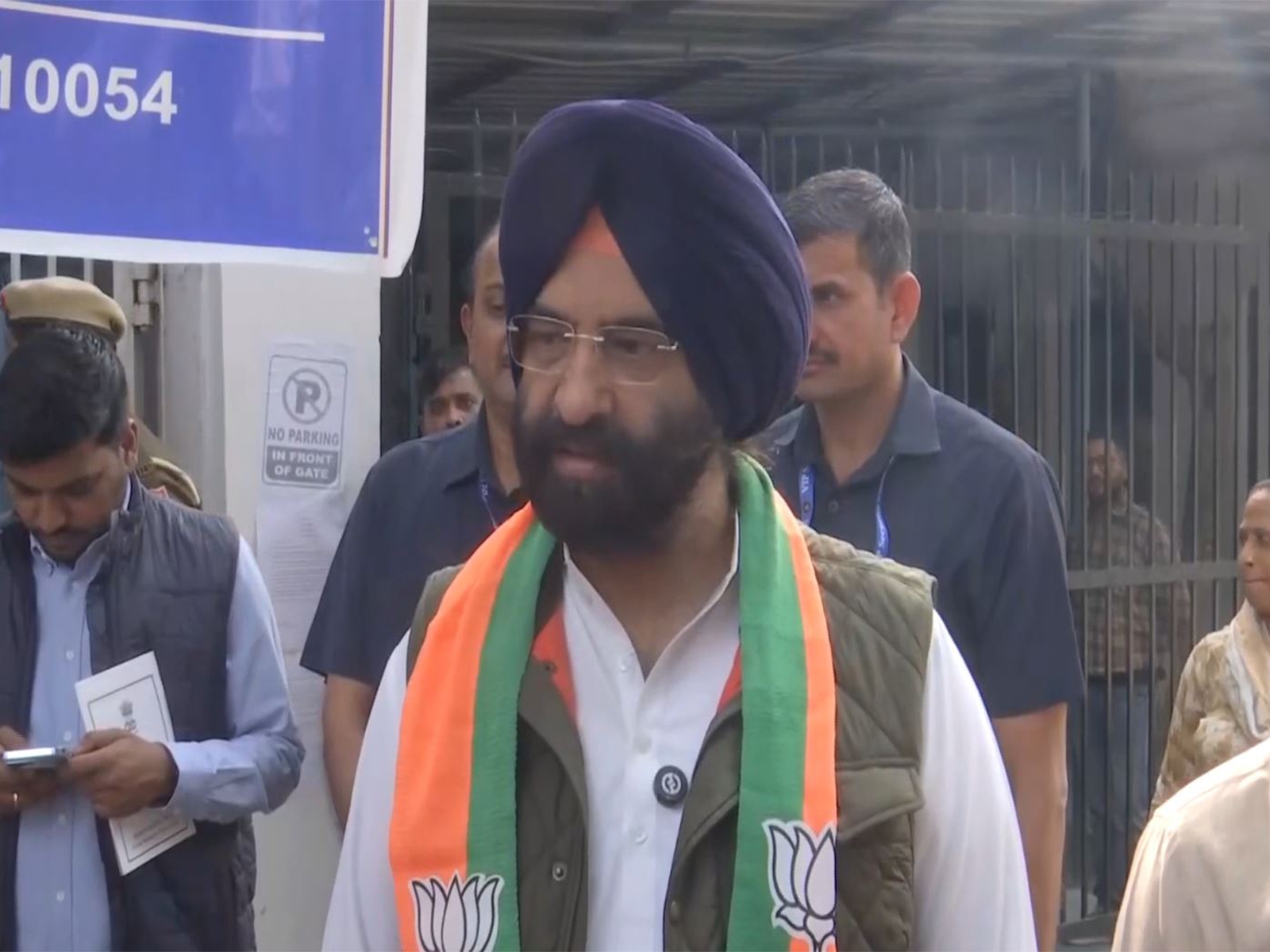

Shashank Manohar's decision to leave the Board to its devices and find comfort in the office of the International Cricket Council's 'independent chairman' has imposed this election, with BCCI secretary Anurag Thakur among those touted to be in the running for the top chair.

Politicians have shaped the Board

It is curious how career politicians of varying hues cast their differences aside and come together to protect their turf - their hold over BCCI.

Of course, there have been politicians, bureaucrats and industrialists who have served the Board well. After all, a society is a mix of its people, and the BCCI can only draw from the talent pool within the country.

But what is it about cricket administration that makes them close ranks, despite their political rivalries, which causes important legislation to remain in limbo for long periods of time?

Clearly, the spotlight and the whiff of financial power - often with only a little responsibility - combine to make a heady potion.

The interest - and that word is an understatement - evinced by politicians in cricket is not recent. Come to think of it, the heads of princely states played a role in the evolution of the sport in the country. The umbilical cord connecting cricket and politicians could never be snapped, even though a Delhi industrialist, GE Grant Govan, served as the first president of BCCI.

From Sir Sikandar Hayat Khan (1933-35) through Mohammad Hamidullah Khan (Nawab of Bhopal), KM Digvijaysinji (Jamsahib of Nawanagar) to Paramasivan Subbarayan (1937-46), politicians helmed the Board.

Maharaja of Baroda Fatehsinghrao Gaekwad (1963-66) and Surjit Singh Majithia (1956-58) had brief terms, before SK Wankhede (1980-82), NKP Salve (1982-85), Madhavrao Scindia (1990-1993) and Sharad Pawar (2005-08) ruled the roost at the top of BCCI.

Back in 1945, the widely-respected columnist Berry Sarbadhikari wrote of how the organisation of the game in India bore some of the unhappy features of an alien government, set up for specific purposes, most of which had nothing to do with playing cricket.

And, a couple of years later, the renowned Prof DB Deodhar wrote of how politics harshly impinged on all sports, especially cricket.

Perhaps, we now pay a bit more attention to the men who run the sport, and hence, it is more apparent to even to those with cursory interest that BCCI is a veritable cosy club.

How else can one explain decisions like rehabilitating some of those who have lost in the Board elections with plum posts in various committees?

A happy, united bunch?

Yet, is the BCCI really one happy, united bunch, a mutual admiration society without fissures? Not really. From its inception, there have been instances of groupism that occur from time to time.

But when faced with external threats - or by intrusion from an unknown element - the Board quickly comes together, thanks to an age-old system of reward and punishment.

There was a time when plum assignments or membership to key sub-committees were used as attractions to either reward loyalists, or even rivals, to keep the flock together.

And in the past few years, thanks to the influx of money through the IPL route, not to speak of broadcast rights revenues, they found a more alluring carrot to dangle before their constituents.

Those aspiring to make inroads into BCCI portals have found it hard to breach the citadel, and those who break ranks have paid with exclusion - and their associations punished as well.

Tired of being left on the fringes, those sulking give up any pretences of being in the opposition, and fall in line. Or, they pay a bigger price by being reduced to bystanders even in their state associations.

The powers-that-be have no hesitation in dumping someone by the roadside, be it Jagmohan Dalmiya, Lalit Modi or N Srinivasan.

Back in 2006, Dalmiya who had been Board treasurer, secretary and president, as well as the ICC president, was given a life ban for alleged misappropriation. That ban was revoked four years later.

Modi was suspended from BCCI in 2010, and three years later, handed a life ban on charges of misconduct and indiscipline.

The example set by the IOC

Then again, the BCCI is not alone in employing such tactics. World sport's highest body, the International Olympic Committee (IOC), has not set the best example in deciding the electoral college which determines most decisions.

Even the reforms forced upon IOC in the wake of a scandal around the allotment of the 2002 Winter Olympic Games come across as appeasement. At the end of the day, 70 individual members retain control of the IOC.

Come to think of it, the IOC is more or less an exclusive club itself. Let us cast our minds back to former IOC vice-president and one-time presidential candidate Richard Pound's strong reference to the IOC's resistance to change. Of course, his focus was how European administrators controlled most sport.

"In the 114-year history of IOC, only one of its presidents (Avery Brundage) has been non-European... It would be an interesting statistical analysis to undertake to determine the number or percentage of European presidents of international sports federations over the years as well as the locations of their headquarters," he said in 2008.

Worse, Pound pointed out that the IOC's influence on world sport grew because of growing revenues from sale of broadcast rights. "Political considerations have led financial support derived from television revenues to be administered and financed on a continental basis, a decision explicable only on a political basis, not on one that would maximise the impact of and accountability for the funding involved," he said.

A 'charitable' society

The BCCI story, unfolding before the Supreme Court, does not sound very different, does it?

Formed in 1928, but registered under the Societies Registration Act, 1860, only in 1940, BCCI was subsequently registered as a Charitable Society under the Tamil Nadu Societies Registration Act, 1975, which came into effect on 22 April 1978.

In the past few years, a number of government departments and courts of law have looked at it as more than just a charitable organisation.

The only way in which the nature of sports administration can change is for Parliament to enact a law under which such organisations are registered under Section 25 of the Companies Act.

But with so many influential members wearing legislators' hats, it has been left to the Supreme Court to try and change the order of the closed society.

First published: 20 May 2016, 21:31 IST

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)