Former president APJ Abdul Kalam, 83, passed away on 27 July, following a cardiac arrest in Shillong.

In the days ahead, many will remember him through obituaries and anecdotes. But perhaps the best insight on him is through his own words and memories.

These excerpts from his autobiography Wings of Fire describe some of the most defining places, people and moments in his life.

Rameswaram: the landscape of his childhood

Rameswaram, a temple town in Tamil Nadu, played a seminal role in shaping President Kalam. In his book, he describes with evocative detail the pilgrims catching a boat out at sea and the relationships between the Hindus and Muslims of his childhood.

Though the society around him was rigid and stratified along caste and religious lines, Kalam was fortunate to have some remarkable people in his life, who broke through these barriers and seeded in him a firmly plural and syncretic imagination.

His father's friendship with Pakshi Lakshmana Sastry, the high priest of Rameswaram temple, forms one of his most 'vivid memories':

"The high priest of Rameswaram temple, Pakshi Lakshmana Sastry, was a very close friend of my father's. One of the most vivid memories of my early childhood is of the two men, each in his traditional attire, discussing spiritual matters.

When I was old enough to ask questions, I asked my father about the relevance of prayer. My father told me there was nothing mysterious about prayer. Rather, prayer made possible a communion of the spirit between people.

"When you pray," he said, "you transcend your body and become a part of the cosmos, which knows no division of wealth, age, caste, or creed."

My father could convey complex spiritual concepts in very simple, down-to-earth Tamil."

Kalam had people in his life who broke through barriers and seeded in him a plural and syncretic imagination

Kalam also describes how easily his family enabled - and sometimes participated - in the festivals and rituals of the Hindus:

"During the annual Shri Sita Rama Kalyanam ceremony, our family used to arrange boats with a special platform for carrying idols of the Lord from the temple to the marriage site, situated in the middle of the pond called Rama Tirtha which was near our house.

Events from the Ramayana and from the life of the Prophet were the bedtime stories my mother and grandmother would tell the children in our family."

Jallaluddin: his door to a wider world

Another key figure of Kalam's childhood was Ahmed Jallaluddin, a relative who eventually married his sister and was 15 years older than him.

In this vivid passage, Kalam describes several key strands of his life: his curiosity about spirituality, his love of learning, and how, over long walks by the sea, Jallaluddin became his door to a wider world.

He also describes with an almost unconscious poignancy the flow of two mighty faiths, and how they commingled in his imagination, as the two friends visited and prayed at both the local mosque and a Shiva temple.

"We used to go for long walks together every evening. As we started from Mosque Street and made our way towards the sandy shores of the island, Jallaluddin and I talked mainly of spiritual matters.

The atmosphere of Rameswaram, with its flocking pilgrims, was conducive to such discussion.

Our first halt would be at the imposing temple of Lord Shiva. Circling around the temple with the same reverence as any pilgrim from a distant part of the country, we felt a flow of energy pass through us.

Jallaluddin would talk about God as if he had a working partnership with Him. He would present all his doubts to God as if He were standing nearby to dispose of them.

I would stare at Jallaluddin and then look towards the large groups of pilgrims around the temple, taking holy dips in the sea, performing rituals and reciting prayers with a sense of respect towards the same Unknown, whom we treat as the formless Almighty.

I never doubted that the prayers in the temple reached the same destination as the ones offered in our mosque. I only wondered whether Jallaluddin had any other special connection to God.

Jallaluddin's schooling had been limited, principally because of his family's straitened circumstances. This may have been the reason why he always encouraged me to excel in my studies and enjoyed my success vicariously.

Never did I find the slightest trace of resentment in Jallaluddin for his deprivation. Rather, he was always full of gratitude for whatever life had chosen to give him.

Incidentally, at the time I speak of, he was the only person on the entire island who could write English. He wrote letters for almost anybody in need, be they letters of application or otherwise.

Nobody of my acquaintance, either in my family or in the neighbourhood even had Jallaluddin's level of education or any links of consequence with the outside world.

Jallaluddin always spoke to me about educated people, of scientific discoveries, of contemporary literature, and of the achievements of medical science. It was he who made me aware of a "brave, new world" beyond our narrow confines."

Potter's wheel: the clay that made Kalam's character

Books were a scarce commodity in Kalam's childhood. But a revolutionary or former militant nationalist called STR Manickam had a sizeable personal library. This became the nursery of Kalam's mind.

Periyar EV Ramaswamy's powerful movement against high-caste Hindus, which was sweeping the land at the time, was another life-altering influence. And a paper called Dinamani, which was distributed by his first cousin Samsuddin. (Samsuddin helped him earn his first wages as a child. Kalam could remember the keen pride of that even "half a century later".)

Here's how he describes these key figures of his childhood and the role they played in shaping his adult self:

"Every child is born, with some inherited characteristics, into a specific socio-economic and emotional environment, and trained in certain ways by figures of authority.

I inherited honesty and self-discipline from my father; from my mother, I inherited faith in goodness and deep kindness and so did my three brothers and sister.

But it was the time I spent with Jallaluddin and Samsuddin that perhaps contributed most to the uniqueness of my childhood and made all the difference in my later life.

The unschooled wisdom of Jallaluddin and Samsuddin was so intuitive and responsive to non-verbal messages that I can unhesitatingly attribute my subsequently manifested creativity to their company in my childhood."

Three friends and the first ruptures of innocence

Kalam had three close friends as a child. All three - Ramanadha Sastry, Aravindan, and Sivapraksan - were from orthodox Hindu Brahmin families. Ramanadha, in fact, was the son of Lakshmana Sastry, the high priest of the Shiva temple, and a friend of Kalam's father.

"I inherited honesty and self-discipline from my father; from my mother, I inherited faith in goodness"

But the harsh realities of bigotry were always only a breath away. Here, Kalam describes an incident that became a core trace memory for him:

"One day when I was in the fifth standard at the Rameswaram Elementary School, a new teacher came to our class.

I used to wear a cap which marked me as a Muslim, and I always sat in the front row next to Ramanadha Sastry, who wore a sacred thread.

The new teacher could not stomach a Hindu priest's son sitting with a Muslim boy. In accordance with our social ranking, as the new teacher saw it, I was asked to go and sit on the back bench. I felt very sad, and so did Ramanadha Sastry.

He looked utterly downcast as I shifted to my seat in the last row. The image of him weeping when I shifted to the last row left a lasting impression on me.

After school, we went home and told our respective parents about the incident. Lakshmana Sastry summoned the teacher, and in our presence, told the teacher that he should not spread the poison of social inequality and communal intolerance in the minds of innocent children. He bluntly asked the teacher to either apologize or quit the school and the island.

Not only did the teacher regret his behaviour, but the strong sense of conviction Lakshmana Sastry conveyed ultimately reformed this young teacher."

Science and the iconoclast: another seminal figure

In his presidency, Kalam was perhaps most admired for his spontaneous iconoclasm, his refusal to play by the rule, unless the rule made sense to him.

Again, the figures of his childhood may have had something to do with this. One towering influence was his science teacher, Sivasubramania Iyer.

Here's how Kalam remembers him:

"My science teacher Sivasubramania Iyer, though an orthodox Brahmin with a very conservative wife, was something of a rebel.

He did his best to break social barriers so that people from varying backgrounds could mingle easily. He used to spend hours with me and would say, "Kalam, I want you to develop so that you are on par with the highly educated people of the big cities."

One day, he invited me to his home for a meal. His wife was horrified at the idea of a Muslim boy being invited to dine in her ritually pure kitchen. She refused to serve me in her kitchen.

Sivasubramania Iyer was not perturbed, nor did he get angry with his wife, but instead, served me with his own hands and sat down beside me to eat his meal.

His wife watched us from behind the kitchen door. I wondered whether she had observed any difference in the way I ate rice, drank water or cleaned the floor after the meal.

When I was leaving his house, Sivasubramania Iyer invited me to join him for dinner again the next weekend.

Observing my hesitation, he told me not to get upset, saying, "Once you decide to change the system, such problems have to be confronted."

When I visited his house the next week, Sivasubramania Iyer's wife took me inside her kitchen and served me food with her own hands."

Rites of passage: the paces of formal learning

When Kalam was in his early teens, he became a boarding school student at Shwartz High School, at Ramanathapuram. He did not quite fit in there. Homesick, yet determined, he soldiered on because he knew his father dreamed of him becoming a Collector.

After school, Kalam pursued a BSc in physics at St Joseph's College. But after he had got his degree, he realised physics was not his calling. Soon after, he applied to the Madras Institute of Technology (MIT) and made it through.

Admission was an expensive affair. He needed a thousand rupees that his father did not have. His sister, Zohara, stepped forward and mortgaged her gold bangles and chain for him.

Kalam writes:

"I was deeply touched by her determination to see me educated and by her faith in my abilities. I vowed to release her bangles from mortgage with my own earnings. The only way before me to earn money at that point of time was to study hard and get a scholarship. I went ahead at full steam."

Science and the man: Kalam at DRDO

After finishing engineering, Kalam first worked at the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) as a scientist.

Later he became a part of the INCOSPAR committee under space scientist Vikram Sarabhai. While he was working under Sarabhai, Kalam took up a rocket-assisted take-off system (RATO) project.

Here too, he tried to bend rules to make new things possible:

"One day, while working late in the office, which was quite routine after I took up the RATO project, I saw a young colleague, Jaya Chandra Babu going home. I called him into my office and did a bit of loud thinking. "Do you have any suggestions?" I asked.

The next evening, Babu came to me before the appointed time. "We can do it, sir! The RATO system can be made without imports. The only hurdle is the inherent inelasticity in the approach of the organization towards procurement and sub-contracting, which would be the two major thrust areas to avoid imports."

He gave me seven points, or, rather, asked for seven liberties. These demands were unheard of in government establishments, which tend to be conservative, yet I could see the soundness of his proposition.

The RATO project was a new game and there was nothing wrong if it was to be played with a new set of rules. I weighed all the pros and cons of Babu's suggestions for a whole night and finally decided to present them to Prof. Sarabhai.

Hearing my plea for administrative liberalization and seeing the merits behind it, Prof. Sarabhai approved the proposals without a second thought."

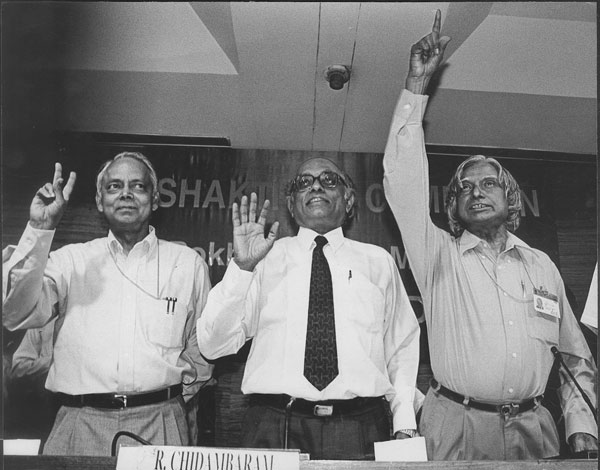

Kalam at DRDO. Photo: Prakash Singh/Hindustan Times/Getty Images

The loss of childhood anchors

Soon after, Kalam moved to bigger projects. In 1969, he was hired at the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) as the project director of India's first Satellite Launch Vehicle (SLV-III).

One day, while working on SLV-III, Kalam got some bad news. This passage, in a sense, sums up how crucial the figures of his childhood had been:

"My brother-in-law and mentor Jenab Ahmed Jallaludin, was no more.

For a couple of minutes, I was immobilized, I could not think, could not feel anything. When I could focus on my surroundings once more and attempted to participate in the work, I found myself talking incoherently-and then I realised that, with Jallaluddin, a part of me had passed away too.

Death has never frightened me. After all, everyone has to go one day. But perhaps Jallaluddin went a little too early, a little too soon. I could not bring myself to stay for long at home. I felt the whole of my inner self drowning in a sort of anxious agitation, and inner conflicts between my personal and my professional life."

The persistent force of his childhood is captured again in another moment of triumph: on 18 July 1980, India's first Satellite Launch Vehicle (SLV-III) lifted off. But Kalam felt strangely empty:

"The whole nation was excited.

India had made its entry into the small group of nations which possessed satellite launch capability. Newspapers carried news of the event in their headlines. Radio and television stations aired special programmes.

Parliament greeted the achievement with the thumping of desks. It was both the culmination of a national dream, and the beginning of a very important phase in our nation's history. Prof. Satish Dhawan, Chairman ISRO, threw his customary guardedness to the winds and announced that it was now well within our ability to explore space.

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi cabled her congratulations. But the most important reaction was that of the Indian scientific community-everybody was proud of this hundred per cent indigenous effort.

I experienced mixed feelings. I was happy to achieve the success which had been evading me for the past two decades, but I was sad because the people who had inspired me were no longer there to share my joy: my father, my brother-in-law Jallaluddin, and Prof. Sarabhai."

The epitaph: Wings of fire, the reason for being

Kalam is rightly feted for his presidency. It is a triumphant parable of how the most disadvantaged Indian can make it to the highest office.

It is part of Kalam's sentience that his success did not make him blind to the meaning of his life for others. He wanted to do what the figures of his childhood had done for him: open doorways into a wider world.

Right through his presidency and beyond, therefore, he continued to engage with the young. He wanted his life to speak for something. He wanted to instill hope.

He would probably count it a blessing that he went down doing what he loved: he died among students, in the midst of an inspirational talk.

He wanted his life to speak for something. He wanted to instill hope

Here's how Kalam summed up the significance of his own life. It could well pass for his epitaph:

"The biggest problem Indian youth faced, I felt, was a lack of clarity of vision, a lack of direction. It was then that I decided to write about the circumstances and people who made me what I am today.

The idea was not merely to pay tribute to some individuals or highlight certain aspects of my life. What I wanted to say was that no one, however poor, underprivileged or small, need feel disheartened about life. Problems are a part of life.

I will not be presumptuous enough to say that my life can be a role model for anybody; but some poor child living in an obscure place, in an underprivileged social setting may find a little solace in the way my destiny has been shaped.

It could perhaps help such children liberate themselves from the bondage of their illusory backwardness and hopelessness."

That is a powerful message to leave as a footprint: the hope that backwardness and poverty can be turned into merely an illusory bondage.

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)