Seen Narcos and think you know Medellin? Think again

This past Friday, Netflix released season two of its much-lauded original series, Narcos. The show, a dramatised retelling of the rise and fall of drug kingpin Pablo Escobar, takes us on a bullet-filled and bloody tour of Pablo's hometown of Medellin.

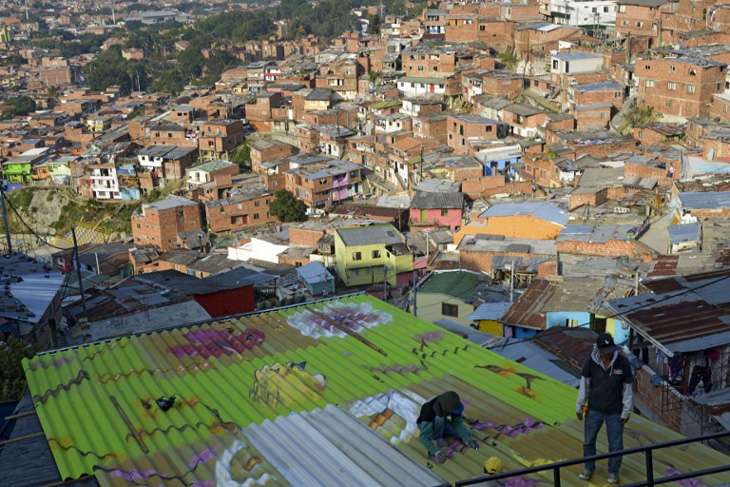

As we travel through Medellin's barrios, we're given glimpses of the violence and poverty that defined the city during the decades of Escobar's bloody reign. Narrow streets, shady winding stairways, shanty housing and a general lack of infrastructure are all hallmarks of the Medellin we are introduced to in the show.

This, coupled with the drug-related violence that epitomised Escobar's 20 year reign, leaves us with an image of a battered, and possibly permanently broken town. With 6,349 killings in 1991 alone, it's not hard to understand this perception.

Also read - Cocaine, arms and peace: facts & figures about Colombia's historic pact with FARC

However, while Medellin may appear in the show as a rundown town, the Medellin of today is a far cry from that. In a miraculous turnaround since Escobar's passing, it has risen, like a phoenix from the ashes, to become one of Colombia's best and most developed cities, even winning the prestigious Lee Kwan Yew World City Prize.

This is the story of today's Medellin - a city that has discarded the legacy of a dark past to achieve a brighter future.

The decline of Medellin

While Medellin in Narcos may seem like a run down town at best, it was, in reality, always one of Colombia's most major cities. In fact, the real decline of Medellin, into the cocaine and crime capital of Colombia was, in large part, due to the city's growth.

The city, which in the early 1950s had a population in the vicinity of 3,00,000, saw a population explosion. With better medical care, lifespans and birthrates increased causing the population to surge, tripling to a million by 1970.

This overcrowded a city that was absolutely unprepared for these numbers. The poorer classes, unable to afford rent in the centre of the city were forced to move increasingly further out, eventually coming to occupy the hilly, less-accessible areas. Cut off from the opportunities the city centre had to offer, poverty in these barrios was rife.

But it wasn't just economic benefits they were cut off from. Law enforcement in these areas, by virtue of the inaccessibility, was also sparse.

It was this sort of environment that gave birth to criminal elements like Pablo Escobar. Growing unchecked in the shadier areas of the city, they would eventually cast a shadow over the city itself, with the poor barrios coming to define Medellin in the eyes of the wider world, while the city centre was all but forgotten.

Curbing crime

Crime was a part of Medellin long before the cocaine business, though not the violent crime that came to define the narcos. Medellin, with easy access to both the eastern and western coast, had been a smuggling hub since at least the early 50s. The cocaine trade thrived off this set up as well.

However, while there was space for all the players initially, the cocaine market filled up quick. Soon, competition, ridiculously high profits and rampant corruption combined to create a two-decades-long bloodbath that would leave Colombia on the brink.

The watershed moment in the fight against crime came before Escobar's death. In 1991, the bloodiest year of Escobar's reign, a new constitutional assembly was elected and the constitution was amended. This led to a decentralisation of power giving greater impetus to local governments.

This shift in power proved vital in the coming decades. NGOs and civil society stepped up and aided Medellin's now-empowered local government in charting a brighter path for Medellin. Successive mayors did their best to root out corruption and increase investigative powers. Security forces were professionalised nationwide in partnership with the USA and Medellin also reaped the benefits of this.

Victims' groups and NGOs have also been hard at work, trying to keep juveniles and youth at risk of joining crime on the straight and narrow. All of these efforts have seen the crime rate in Medellin today drop by 80% from its 1991 peak.

From lead to gold

Before 2000, Medellin had one claim to fame as far as development went -- a metro system. In fact, the only metro system in Colombia. Unfortunately, corruption in its construction meant the local government was all but bankrupted and couldn't do very much more.

Eventually, to connect the poorer, more removed areas of the city to the city centre, they instituted a cable car system. It might seem small, but its impact was huge. Suddenly, people who'd been marginalised could now make their way easily to the city, finally able to access the opportunity of its financial centres.

However, the real turnaround came in 2003 with the election of Sergio Fajardo as mayor. Fajardo, who'd studied in the US, and had previously both worked with and written on the city of Medellin, changed the approach to urban planning.

He brought in professionals and involved the community. Not satisfied with the barrios being connected by cable cars, his administrations worked to create 'physical interventions' - buildings and structures within poorer neighbourhoods that improved the quality of life.

Also read - Cheat Sheet: 14 things we learned from Sean Penn's epic interview of El Chapo

These ranged from libraries to schools, medical and community centres to museums. Poor neighbourhoods on steep inclines even got outdoor escalators to help people get around. Public spaces were seen as spaces that could bring the community together and were worth investing in.

Importantly, the community worked with the government to decide every change, making these changes more effective.

Education also received a huge boost. Fajardo was effectively the first mayor of Medellin with true control over education in the city, and he threw all his might behind it. Schools were built, older ones were upgraded and teachers were given training and skill development. Education was to be the great equaliser.

While Fajardo has gone on to become governor of Antioquia, the province of which Medellin is a part, the mayors who have succeeded Fajardo have followed his example.

The city today still has problems with cocaine trafficking, money laundering and inequality. Still, to think of Medellin today as the war zone you see in Narcos couldn't be further from the truth.

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)