What is new about the Rajasthan minimum wage notification? I wonder

Nothing new

- The Rajasthan govt recently notified minimum wages for domestic work

- This isn\'t a new move though

Track record

- The state has had a floor-level wage for domestic employers for almost a decade

- But nothing much has changed on the ground

More in the story

- Why setting a minimum wage is not enough to protect domestic workers?

- What is the way out for such workers?

The Vasundhara Raje government revised the minimum wage rate for domestic workers to Rs. 5,642 per month for eight hours of work daily, or Rs. 705 for an hour's work a day.

That rate is inviolate - a worker may perform one task in that one hour or multiple tasks, the wage will remain the same.

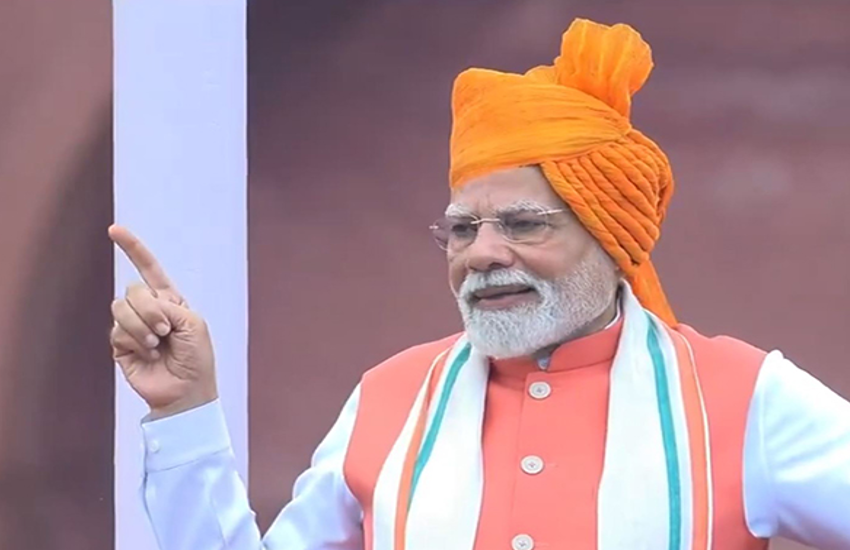

Read: Modi government to hike minimum wages to boost Indian economy

If the work crosses eight hours, the notification stipulates overtime wage at double the hourly rate.

The state's domestic workers were included in the previous minimum wage scheduled, set in 2007, at Rs 264 per hour for a month. This was increased to Rs 543 in 2012. So, the present notification is only a revision of the wage rate.

Not enough to make ends meet

The wage revision is better than no increase at all. But it reflects an underlying devaluation of women's work.

It blatantly violates the norms to fix the minimum wage recommended by the 15th Indian Labour Conference (ILC) along with subsequent Supreme Court orders.

A law can be implemented only when govt shows will and workers negotiate better

Based on the 15th ILC recommendation, the Seventh Pay Commission assigned Rs 9,218 for food and clothing per month and Rs 2,033 towards education, recreation, festivals etc as part of a minimum wage of Rs18,000.

Thus, the minimum wage notified by the Rajasthan government is less than a third of what the government considers a wage that will "ensure a decent standard of living".

Implementation paradox

The estimate on domestic workers in India is highly contested and varied, ranging from 4.75 million to 90 million. What is clear from the figures is how the work done by remain invisible, how enumerators and the workers themselves classify it as 'non-work' - an extension of 'help' or 'assistance' for household chores.

Most domestic workers are part-time workers, employed by several households for different tasks. Their wages are fixed by employers based on the tasks done, not on time spent in each household.

Someone working at four-five households may be putting in eight hours or more, but not for a single employer. None of the employers thus takes responsibility for the additional hours she spends at other households.

Since employers protect their interest collectively, workers should be able to do so too

Which means the Rajasthan notification for overtime wage is difficult to implement for part-time workers. The notification, in fact, states that the hourly wage is Rs 705 irrespective of the number of tasks performed.

This opens up the possibility for increasing the work intensity, which can seriously affect their physical health and even lead to enormous mental stress.

One would think the notification would help at least live-in workers. But even for them it is difficult to implement as it calculating their hours of work is next to impossible as there are:

- no framework for labour inspection

- no requirement for the maintenance of a register by employers

- no clear job description, with tasks specified

- no clear way of calculating hours of work.

The existence of a spread-over in live-in domestic work is used to justify long hours. Given, the nature of the work as well as the employer-employee relation, simply fixing a wage rate is not sufficient.

Also read: Why Rajasthan's labour laws are a peek into India's bleak future

It needs a strict enforcement machinery with regular inspection by labour officials. Employers should be required to maintain and file employee registers with details including the age of the work, the hours put in, overtime, etc.

Criminalisation vs organisation

A minimum wage notification for domestic workers has existed in Rajasthan for almost a decade, but its implementation has been negligible.

The regulation of domestic work has shifted from the domain of protecting the interest of workers to protecting the interest of employers.

In urban centres, especially in the metros, the registration of domestic workers is ensured not to protect the interest of workers but to ensure the safety of employers. Hence police verification has become mandatory for finding employment in urban centres.

Overtime wage is difficult to implement for part-time as well as live-in workers

This criminalisation of domestic work is crucial in controlling workers and creating a social condition led by a middle class that is paranoid of the workers but dependent on them for social mobility.

Crimes committed by domestic workers are exaggerated than mere statistical incidence. However, the reverse is not true.

It remains the employers' prerogative to exploit at free will without being accountable to anyone. Even brutal physical assault, forcible detention, sexual harassment, non-payment of wages to workers, including children, does not criminalise the middle class who perpetuate it.

When it comes to issue of inspection of households, employers raise the bogey of their private space being violated.

The way out

Domestic workers are now unionised in many urban centres. But in most cases those unions have two primary focus: (a) wage and (b) individual complaints.

In most cases they addressed their demands to the government and at best to individual employers as even the unions consider domestic work informal.

Read more: How Rajasthan's human milk banks are paving the way for India to save its babies

But it is not. And it is high time we recognise that: There is a clear employer-employee relation. The employers do represent themselves as a collective in protecting their interest at the local level, at the national level with the government and even internationally in multilateral agencies such as the International Labour Organisation. So should the workers.

At a local level, if resident welfare associations (RWA) can impose police verification on all domestic workers, the workers should be able to negotiate wages and working conditions in that area with RWA representatives.

The minimum wage is less than 1/3 of what govt considers fit for decent standard of living

In areas without organised RWAs, there are often local councils representing the residents. If that too is difficult to identify, workers will have to collectively formulate their demands and negotiate with individual employers collectively.

Any legislation can be implemented only when the government shows will and workers themselves ensure implementation by building capacity to negotiate a better and safe workplace.

Edited by Joyjeet DasMore in Catch:

Bengaluru racism: Tanzanian woman stripped, beaten by mob, car torched for a stranger's crime

MGNREGA@10: In Banda, a job card can be the difference between life and death

80 unseen works of legendary Indian artist Jamini Roy go public

Blaze like no other: Mumbai reels from the effects of a garbage dump fire

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)