#SwachhBharat@1: hear what its foot soldiers are saying

When Narendra Modi met Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg in the US last week and spoke about his mother cleaning people's homes to raise him, residents of Valmiki Colony turned up the volume of their TV sets.

As the prime minister's voice choked and his eyes welled up, many of them let out a bitter laugh.

"If thinking about his mother's life as a cleaner makes him tearful, why don't we Safai Karamcharis get a drop of that sympathy?" says Cheena Ji, 57, a sanitation worker affiliated with the Akhil Bharatiya Safai Mazdoor Sangh, or ABSMS.

"A year ago Modiji picked up a broom and swept some leaves to show his commitment to a Swachh Bharat. But we are the ones actually doing it. When will our lives change?"

Valmiki Colony is a quiet, neat neighbourhood off central Delhi's Mandir Marg. It has a rich history. Some 70 years ago, Mahatma Gandhi, who propagated that the act of sweeping was sacred, would hold his prayer meetings in the locality, then known as Harijan Colony.

Today, it's where most Safai Karamcharis, nearly all of whom belong to the Dalit Valmik caste, reside. It falls under Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal's constituency.

More importantly, it's where Modi launched his Swachh Bharat Abhiyan exactly a year ago on Gandhi Jayanti, a broom in hand and a benevolent smile for the cameras.

So, in the year since, has Bharat become more Swachh? Has the campaign made any difference to the lives of people on whose shoulders the burden of its success rests - the sanitation workers?

Death most foul

When Banwari Lal, 45, a Safai Karamchari with the South Delhi Municipal Corporation, didn't get his salary for five months, he decided to do something about it.

On 27 September, Lal quietly left his home, walked down the tracks from Sarita Vihar station and when nobody was looking, he lay down on the tracks and waited calmly for the next speeding train to crush him to death.

In a note he had left for his family, Lal wrote that since he was riddled with debt and couldn't find the means to repay it, he was left with no option but to end his life.

Lal had been with the SDMC for 18 years, and was regularized in February 2014. That didn't do him much good, however. According to news reports, he hadn't received his arrears of nearly half of last year and no salary since February this year.

Lal's suicide has rattled the community.

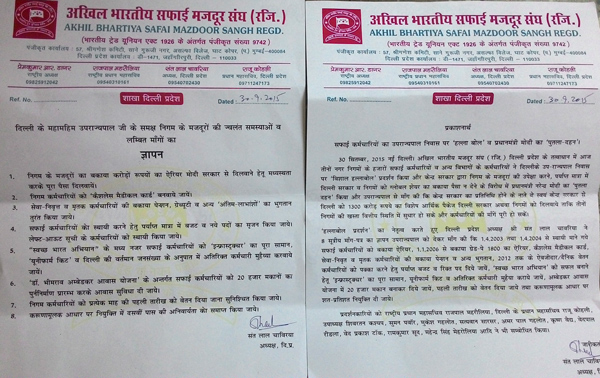

The ABSMS has demanded compensation of Rs 25 lakh for Lal's family and a job for his son Pintu. It has also promised to file an FIR against some officers in Lal's department who they blame for his death, particularly a sanitation superintendent of SDMC.

Santh Lal Chawariya, 52, president of ABSMS' Delhi chapter, alleges that the MCD is mired in corruption and Lal's case has exposed just the tip of the iceberg.

"The system is rotting due to corruption. If a worker is taking a loan against his Provident Fund, he has to pay Rs 10,000-15,000 to those clearing it. In Lal's case, his boss withheld his salary because he refused to pay a bribe. We are going to take this up," Chawariya claims.

Since Lal's letter doesn't mention his boss, it would be difficult for ABSMS to prove harassment. Still, his suicide has raised serious questions about the MCD and the treatment of sanitation workers. The government would have to answer.

Anybody listening?

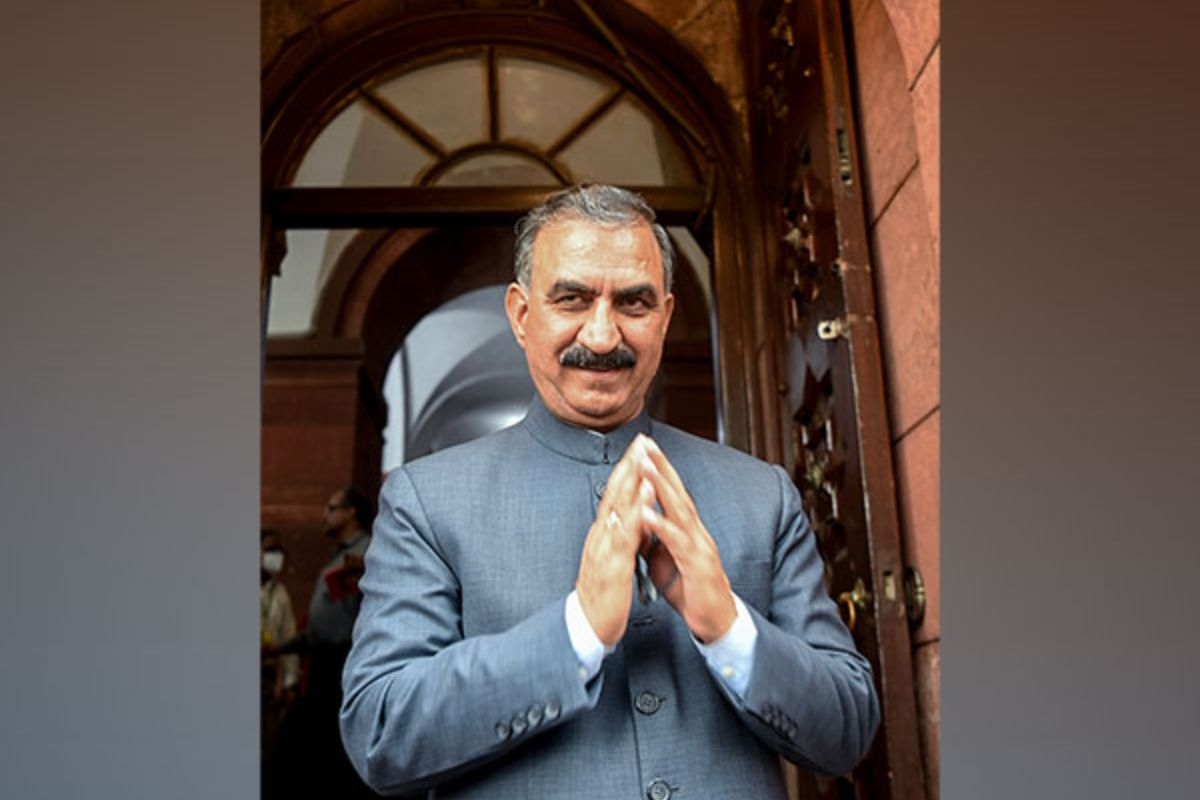

Cheena Ji is heading to Lieutenant Governor Najeeb Jung's house on the morning of 28 September, wearing a yellow headgear for luck. He and his 50 odd colleagues from the ABSMS need all the luck they can to make their protest count.

Walking with Cheena Ji is Satinder, 42. He studied at an ITI, graduating with a one-year diploma in radio and TV repairing. As a starry eyed 18 year old, he dreamt of living a decent life repairing electronic equipment.

After months searching for a job, he was desperate enough to do any work that put some food in his stomach. That's when he joined the MCD as a sweeper for Rs 1,800 a month.

Satinder has been with the MCD for 22 years, but is yet to become permanent employee. He has to support his wife and raise three children on a measly salary of Rs 8,900.

"My house rent is Rs 3,000 and after paying for food and the education of my two daughters and a son, there isn't a penny left. Sometimes we get our salary after 3-4 months, and we are forced to take loans," Satinder says.

In June this year, Satinder was one of the 1,200 Safai Karamcharis who went out to protest after months of not receiving their salaries. Delhi's garbage crisis had mounted to a point where some 1,500 tonnes of garbage were left lying on the street with the karamcharis refusing to clean until their dues were settled.

Photo: Arun Sharma/Hindustan Times via Getty Images

The BJP has ruled the MCD for the past 13 years. The corporations are partly under Centre's purview, while the Delhi government has minimal power over them.

Read: This story about the Delhi garbage strike will make your hair rise

In the battle between the Centre and the state Satinder says, "We are always pushed from one to another."

Satinder's day begins at 5:30 am. He has to reach his starting point in Rohini by 6:30. He cleans a 3,000 sq foot stretch of road with a broom till 2:30 pm, stopping just once for lunch.

It's a hard job - lifting with bare hands garbage and animal excreta once he has swept it into a pile, all the while braving heat, dust, dirt, foul smell and stagnant pools of mosquito-breeding water.

"Gloves?" he asks as if he's hearing the word for the first time.

Satinder has spent 22 years with MCD but is still a temp. He raises 3 kids on a Rs 8,900 salary

Satinder gets no uniform or safety equipment such as goggles, boots, gloves. He doesn't even get a broom. "We keep asking the MCD fellows for brooms, but they never pay heed. So I just buy it myself. How else can I work?" he says.

About a week ago, Satinder came down with a bout of high fever, he vomited several times and felt rashes on his skin. When he went to see a private doctor, he was immediately sent to do a test for dengue. His platelet count turned out to be below 50,000. It was dengue.

He was treated by a retired doctor from Swami Dayanand Hospital. "All the government beds were full. Where could I go? I popped my pills and went to work," he says.

"Last year it was typhoid that cost me heavily. This year it was dengue. I have already spent 3000 rupees on my treatment," he says casually when asked about his health now.

Did the MCD pay for his treatment? No. They didn't even allow him paid sick leave, he says. "I get four days off every month. Any more and it's a salary cut."

In the time Satinder tells his story, the protesters reach the LG's house and submit a letter to him. "The MCD has been running at the cost of the workers' salaries for over a decade now," says Chawariya, holding a copy of the letter.

They are demanding that the MCD pay the arrears from 2003 to 2010 due 23,000 workers, amounting to nearly Rs 1,300 crore, and regularize more employees.

Apart from this, the ABSMS is demanding:

- Safety gear for all 50,000 workers, including gloves, boots, helmets.

- A cashless medical card to help cover hospitalisation costs for the workers, given that they are susceptible to diseases like dengue.

- 20,000 houses for Safai Karamcharis under the Bhimrao Amedkar Awaaz Yojana.

- A pension and gratuity plan for all workers. The currrent pension scheme covers only a section of permanent workers.

After striking all afternoon in the sun, Chawariya and his colleagues finally hear from the LG. "Go ask the chief minister," is his response.

"Now we will have to plan to put up these demands to Kejriwal. Nobody cares about our demands," Chawariya says, visibly sapped of energy.

Small but significant change

Back in Valmiki Colony, Dolly, 32, is just getting back from sweeping a 2-km stretch of a dusty road in J block, Circle 4, near Birla Mandir. She had left home at 6 am. Now, it's nearing 2:30 pm.

She rings the bell and her older son opens the door. She invites us into her cozy two-room flat. Her son offers us chilled coke. Dolly asks if we'd like the AC on and freshens up.

Soon, her husband, Gulal, 38, walks in, wearing a crisp formal shirt and trousers. He takes off his polished shoes and sits down on the sofa. "I'm a sewer man. I've been with the NDMC for the last 20 years," he says.

Forget goggles, boots, gloves, MCD doesn't give me a broom. I've to buy it myself, says MCD worker

Dolly and Gulal are the rare rags-to-riches story within the gambit of Delhi's municipal jobs. It took them 15 years to earn the comfort and warmth of a home they enjoy today, unlike most of Delhi's struggling Safai Karamcharis battling a daily fight to just survive. Gulal is a permanent worker earning Rs 32,000 a month and Dolly earns 7,000 since she is still a temp. They got the house when Gulal was regularized in 2010.

Some of it is feels like sheer luck.

"If you are with the NDMC in Nayi Dilli, life is good. We are well taken care of. My wife will become permanent next year, hopefully, then she will get close to Rs 20,000 and the benefit of medical insurance," says Gulal, beaming.

Twenty years ago, he used to get down manholes to clean sewers. Today, he does that with a machine. "One is called a Jetty machine and another is called a suction machine. Both can clear any clog, no matter how severe. We don't get humans to go down deep manholes any more," he says.

"Especially since the Supreme Court banned manual scavenging in 2008, if a manhole is more than 4 feet deep, machines are called to clear it," he adds, perhaps unaware that the practice hasn't really died out.

Read: Bharat Ratnas: the Clean India army every Indian must meet

Has Swachh Bharat changed anything Gulal and Dolly?

"We had all this from before. But I think Swachh Bharat has done one thing. It has made us realise that cleanliness is important. People now think twice before throwing something on the street," says Dolly, adding that when the public takes cleanliness seriously, it makes the sanitation workers' job easier.

Also, the campaign has "made us think of our jobs as important and dignified," Dolly says. "We're helping keep the country clean. Sweeping the streets isn't seen as a lowly job any more."

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)