Drought, death & destroyed crops: just how much more can Marathwada take

Extreme situation

- Nivrutti Sathe, a father of two, committed suicide after a bad monsoon destroyed his soyabean crop

- Nivrutti had thought out of box - used a Rs 2 lakh loan to cart river silt on to his farm; yet he failed

- Suicides have become rampant as a 51% deficit in rainfall has dried up fields

Distressed economy

- Sugarcane farmers started preparations from last October, only to be disappointed

- The failed sugarcane crop has left about 50 sugar mills with little raw material

- If mills remain shut, many labourers will lose out on a season of work

Dry run

- The crisis has even affected drinking water supply

- Farmers have started boring deep into fields, eating into aquifer reserves

- Unscrupulous water plants have sprung up in the area

A gloomy future

- People have started cutting down on health, education expenses

- The situation may lead to mass migration

- Marathwada may eventually turn into a desert

After a spate of dry spells, Nivrutti Sathe took a calculated risk in April as he geared up for another cropping season. He decided to transfer silted soil from a dried-up riverbed to his three-acre-farmland in a remote village of Hasegaon in Latur district of Maharashtra's Marathwada region.

The process was expensive, but Nivrutti was sure of a good return on his investment as the silt would enhance his yield. He borrowed Rs 2 lakh from a local moneylender, zeroed in on a riverbed around 10 kilometers from his tin-roofed house and carted soil from there to his farm for nearly two months.

By the end of May the farm, extending up to the Sathe's backyard, was covered with river silt. In early June, Marathwada was blessed by pre-monsoon showers - a rarity, considering the weather patterns in the last decade.

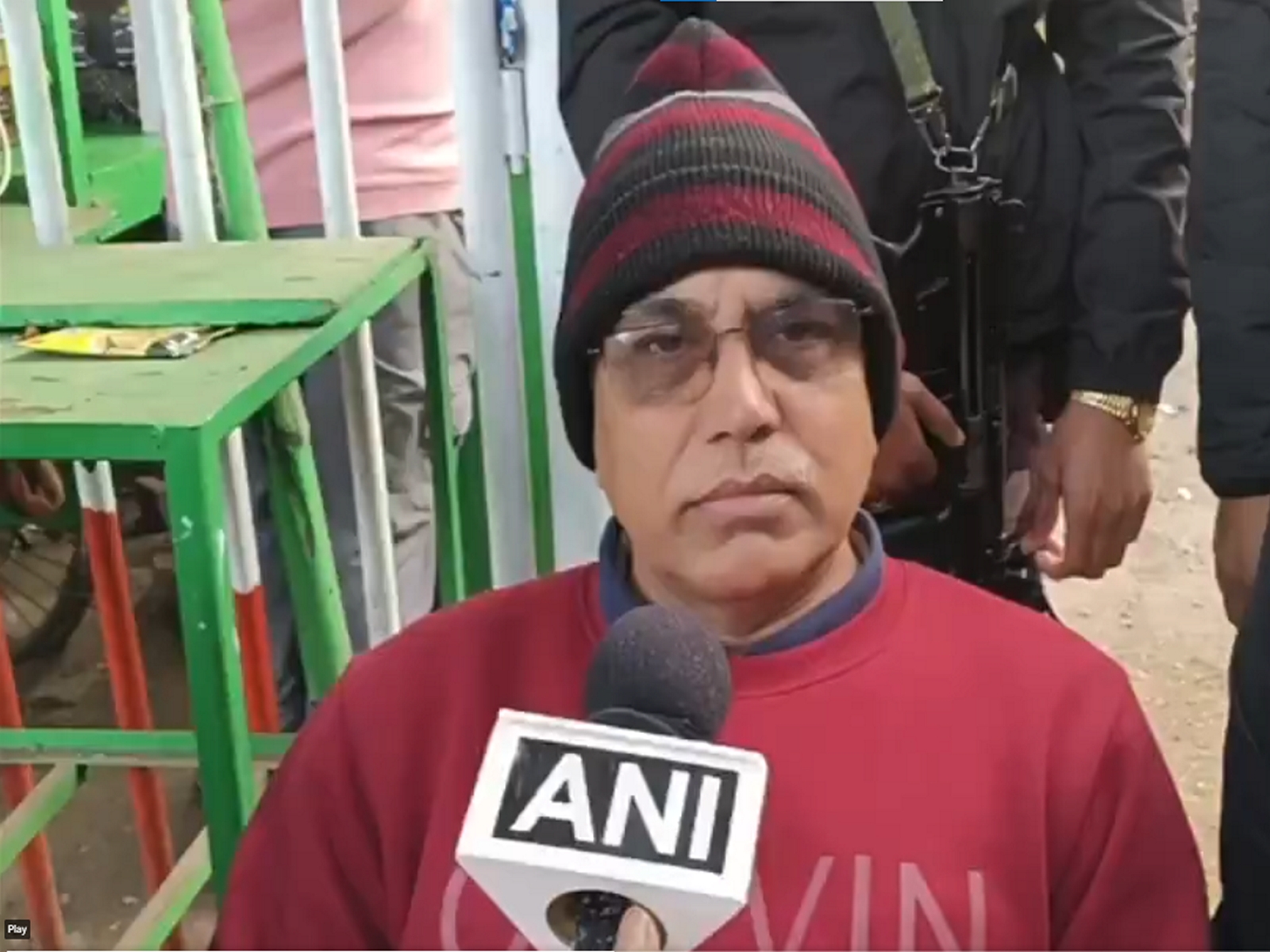

The rainfall encouraged Nivrutti to sow his fields with vigour. "The sowing was promising," says Prakash Sathe, Nivrutti's father. "It was just a matter of reasonable rainfall in the next two months."

But the rain gods turned deceptive: The pre-monsoon downpour was followed by a 45-day dry spell. The region, which normally receives around 780 millimeters of rainfall during monsoons, has got only 259 mm this season. Figures from the Indian Meterological Department indicate an ominous 51% deficit.

Nivrutti could not reap what he sowed: by mid-July, his soyabean crop dried up, bringing to nought his efforts and the investment. He had to pay back the loan without the crop on which he was banking, and also take look after his family. Nivrutti's daughter had turned six and his son was just four.

In the last week of July, Nivrutti gave up. One morning he left home to answer the call of nature. An hour later his mother Bharatbai went to the backyard to dispose waste and found her son hanging from a tree.

"I ran and hugged him," she says, a lump forming in her throat, as Nivrutti's son fiddles around on her lap. "The previous night, we told him to calm down. He was distressed, but nobody imagined he would take such a drastic step."

Prakash defends his son: "The idea to bring in the silted soil was correct. The weather failed him."

A bitter crop

This is the third drought in Marathwada in recent years - each more acute than the previous. Officials estimate that at least 70% of this year's Kharif crop has failed.

More than 600 farmers have committed suicide so far this year, according to Umakant Dangat, divisional commissioner of Aurangabad and the officer in charge of the eight Marathwada districts.

Travelling through the region, one comes across one parched riverbed after another and miles of desolate cotton and soyabean farms, crops barely reaching one's ankle. Normally, the stems would grow waist-high, at times even chest-high.

The story is the same with sugarcane, another major crop in Marathwada for which farmers started preparing since as far back as last October. While the water requirement of soyabean is moderate, sugarcane is a water guzzler.

"From October to March, we drew out water from borewells and wells," says Baderam Bade, who owns a five-acre holding in Devdahifal, Beed. "After that we used drip irrigation until June." By then the monsoon was supposed to take over.

But the 45-day dry spell damaged the sugarcane crop. "It did rain a little in July. But by then the crop had dried," says Bade, who had invested around Rs 75,000. "With what I have at the moment, I cannot make a penny."

"The quantity of sugarcane deemed fit to be bought has halved," says Vilas Sonawane, managing director of Majalgaon Sugarcane Factory in Beed.

The truncated sugarcane is now being used as fodder for livestock, says Bade standing in his farm amid a crop that looks like a toad under the harrow. Normally, a field ready for harvest can conceal a human being.

"I should have made around Rs 3 lakh. This drought has affected my income for two years," he regrets.

Bade has a loan of almost a lakh and has to shell out another Rs 80,000 a year for his son's education in Nagpur. In such distress, even non-issues lead to serious altercations within family and between neighbors, says he.

"We, as the bread winners of the household, feel ashamed to look at our family members and livestock."

Ripple effect

The slump in sugarcane production has derailed the economy revolving around it. Factories, which generally book labourers in July, have not yet approached the contractors.

"Factories say they cannot afford it," says a contractor who arranges for labourers for various sugar mills in Beed. "Many said they might even remain shut this season."

Sugarcane mills were due to start production in a month-and-a-half, but they are not in a position to do so.

"Factories which needed six months for the crushing process will take just two months this time," says Sonawane. "The income of labourers - generally about a lakh in that period - would be reduced to a third of that."

Moreover, international demand for sugar has decreased with the ascent of Brazil in the market, reducing selling prices to Rs 22 a kilo from Rs 34.

That has forced sugarcane factories into severe debt. "We lost Rs 600 per ton," says Sonawane. "At 6 lakh tons a year that we produce that comes to Rs 36 crore. Out of that Rs 7 crores has to be paid to farmers."

Every such factory, and there are 50 in Marathwada, has incurred losses - some even more than the Majalgaon mill - and owe significant amounts to farmers.

Parched throats

The crisis has extended to drinking water as well, with 11 major reservoirs of Marathwada containing less than 10% of the water they can hold. Manjra and Terna, two important dams on which Latur survives, have dried up.

The city now receives water once in 15 days, which may reduce to once a month. The villages in the area are even worse off.

According to the district collector, the existing stock of water would last merely a month-and-a-half. There is a plan to use the railways to fetch water from Ujjani, officials say.

This has led to the proliferation of a number of unauthorised water suppliers, claims Pramod Mundada, the owner of Sunrich Aqua, the largest bottled water plant in the area and among the few authorised units.

"They do not adhere to rules nor conduct any test," he says. "Helpless villagers end up buying adulterated water." Padlocked water tanks have become a common sight after a few instances of water theft were reported in Latur.

Impending disaster

Marathwada may be headed towards desertification, believe experts. "Considering the standards of water management and governance, it appears that an environmental disaster is in the making," says Pradeep Purandare, a former expert member of the Marathwada Statutory Development Board.

The region has 438 cubic meters of surface water per capita. Ideally it should be 1,700 cubic metres, according to hydrologists.

According to Purandare, this drought is man-made and there would be no water left for farming if urbanisation continues. "Urbanisation leads to the use of concrete, which kills tiny water bodies and affect the ground water recharge," he says.

The signs are glaring - 61 of Marathwada's 76 talukas have reported a critical drop in ground water levels. The trend alarmingly coincides with a spree of digging of wells and borewells in farms.

With a water tale that is depleting at an alarming rate, Marathwada is moving towards desertification

"Panic-stricken farmers dig deep," says Sanjeev Unhale, senior journalist from Aurangabad. "But they do not realise that deep aquifer takes a thousand years to fill and should not be disturbed. Digging 20-25 meters is understandable, but farmers go on up to 1,000 feet (300 metres)."

The paucity of water has added a new dimension to production costs for farmers. "Water and fodder were never a major factor. But now we have to save up," says Prakash Sathe.

Sathe, who has three cows and makes a bit of money selling milk products, says the two additional dimensions have made his livestock a great burden. "I make Rs 300 a day from milk products. But the maintenance cost has now gone up to Rs 10,000 a month," he says.

Dangat says relief is underway, especially in the three worst-hit areas of Beed, Latur and Osmanabad. "Water tankers are being sent to parched areas and the number of cattle camps are being increased. This will take a lot of load off farmers," he adds.

Missing governance

Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis toured Marathwada last week to address farmers. Freshly painted zebra crossings look ludicrous, ending abruptly in the middle of divider-less roads: Apparently only that side of the road was painted on which the CM's motorcade rolled.

In Osmanabad, information kiosks were installed for farmers before the visit, but taken off immediately after he left.

Pankaja Munde, the minister for rural development and water conservation, dropped by in the village of Gangamasra in Beed, where farmers had sought permission for collective suicide. She implored them not to indulge in any such act. When a farmer asked her about the enforcement of the Swaminathan Commission, she said, "At the moment, we must address the issues at hand."

Atul Deulgaonkar, joint secretary of the Latur-based Forum of Environmental Journalists of India, says the lack of proactive measures magnify the drought. "Farmers are often at the receiving end of administrative lethargy."

The state's refusal to waive off farm loans during an intense drought has attracted a lot of flak. "When the farmer has a loan with the bank, he has no option but to approach unregistered moneylenders who impose inhuman interest rates," says Deulgaonkar. "If bank loans are waived off, farmers can walk into the bank with a clean slate."

The process of obtaining bank loans needs to be simplified, he says. "If the racket of unregistered moneylenders is to be cracked, the banks need to be more accommodative."

Trickle down

The impact of the drought has percolated to the bottom of the pyramid and is palpable at Latur's reputed grain market. Shopkeepers and vendors sit their idle, reading books or watching television.

Lalit Shah, head of the local Agriculture Produce Market Committee, believes the situation is worse than what it was during the infamous drought of 1972. "I have on 500 bags each of moong and black gram," he says. "It should have be in excess of 5,000 bags each."

If the situation persists, Marathwada could witness mass migration as people would deluge big cities in search of work, fears Shah. People's buying capacity has been curtailed, which has affected the sales of business of garment, footwear and groceries. Some have even cut down spending on health and education.

Doctor Ajit Jagtap, a pediatrician, shares a disquieting experience. "A farmer came to my hospital eight days ago," he says. "His year-old kid had bilateral hernia. It would have cost around Rs 15,000 so I offered to treat the kid at minimal cost and told him to pay in installments. He nodded and promised to be back in some time, but I never saw him again."

Doctor Gajanan Gondhali, a physician, says 80% of the patients in his intensive care unit have mortgaged their land for a health emergency, that too at outrageous rates.

"One patient told me he has mortgaged the papers of his 2-acre farmland for Rs 2 lakh," he says. "Another farmer from Beed had to get his father discharged prematurely."

At a clinic, a farmer from Nanded said he had borrowed Rs 10,000 at an interest of 4% per month for his three-month-old son's treatment.

In many areas, farmers have reportedly withdrawn their kids from schools.

What now

Deulgaonkar believes the micro-level administrative drawbacks in acquiring bank loans or the failure to seize local moneylenders should not overshadow macro-level policies, which demoralize farmers.

"With our imports increasing by the day, farmers do not get fair returns for their food crops," he says. "We have done nothing to protect our farmers during globalization.

He points out the dichotomy of giving sops to corporates but raising a stink at farm subsidies and the non-enforcement of the Swaminathan Commission recommendation. "What kind of a message are we sending out?" asks Deulgaonkar.

As an immediate measure, he says community farming should be promoted. "It decreases production costs as farmers would deal in bulk orders. Moreover, the middleman would not have bragging rights if he is dealing with a vast group, instead of an individual."

In the meantime, farmers across Marathwada have made a last gamble. When it rained in mid-August, many opted for a second round of sowing, including Nivrutti's father Prakash. "What else can we do?" he asks. "That is our only hope of raising some money for the Rabi season."

Marathwada's sky has seen dark clouds occasionally in the last 15 days, but only to wither away. At best, there has been a light drizzle. Prakash, though, needs much more.

"The clouds accumulate, there is thunder, lightening even," he says. "It is all very tantalising." No wonder then, more than half his day is past gazing at the sky. The silted soil still spreads out in his farmland.

First published: 8 September 2015, 8:16 IST

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)