Green clearances: how the NDA govt is dismantling public hearings

The system

- Any planned project needs to have an Environmental Impact Assessment done by an independent agency

- The matter is then referred for a public hearing

- Locals can have their say on how a project would impact them

- The Kondhs of Odisha got Vedanta\'s mining project on the sacred Niyamgiri hill scrapped

The plan

- Slowly but surely, the NDA govt is diluting and dismantling the system of public hearings

- On 3 February, a govt notification took away the right of every state with an international border to question road and pipeline projects

- The govt gave itself the power to exempt all memorial projects coming up in the sea

The future

- A govt-appointed committee to review environmental acts took a dim view of public hearings

- The TSR Subramanian committee stated there was no need for them in industrial areas

- It also said hearings are not necessary where settlements are far away from project sites

- The govt is planning to act on the committee\'s report in the next few months

Public consultations are one of the most hard-won and important legal rights of the people.

For all the faults one can pick in the system of public consultation, it has played a big role in ensuring ordinary people have a say on how the resources around them are used. It enshrines India's democratic spirit.

Every development project in India is always cleared in the name of the people. Public consultations have ensured they have had at least a nominal say in it.

This was a clause in the Environmental Impact Assessment Notification, 2006, and embodies a core mandate of the environment ministry: to protect the environment.

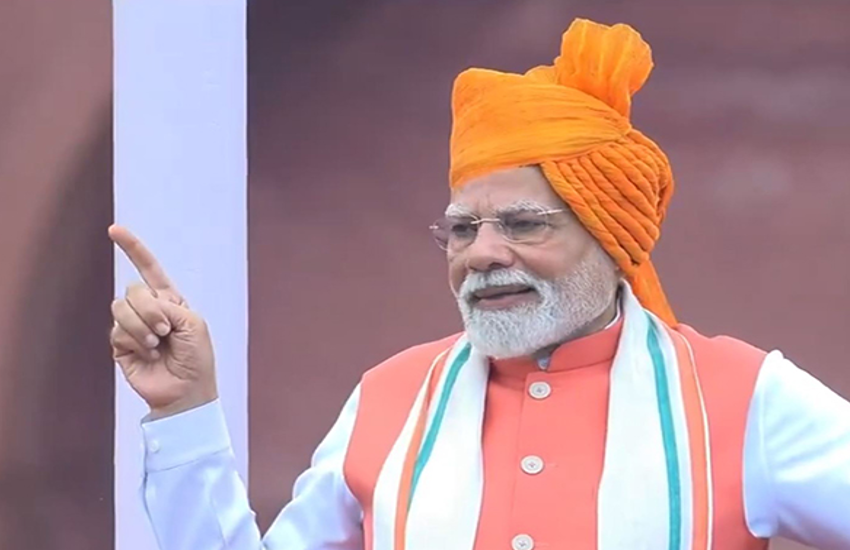

But since the Narendra Modi government came to power in 2014, there has been a systematic effort to dilute - or dismantle - many progressive laws and powers of the environment ministry.

Banning public consultations is one of them.

In the past, different governments have tried to subvert public consultations by imposing section 144 or filling fictitious names in the register. But the environment ministry under Prakash Javadekar has gone one brazen step further.

Since taking office, the ministry has banned or overridden public consultations for a range of projects, including those that involve industrial parks, tribal lands, and highway projects.

Many of these moves are almost a violation of the Constitution and have aroused opposition within the government itself.

Here's how the story is unfolding.

When the Kondhs rose against Vedanta

The Kondh people in Odisha unanimously rejected a bauxite mining project of the multinational Vedanta Group in early 2014, forcing the world to took notice.

The decision turned heads not just because the Kondhs objected to pollution, or the loss of rivers and forests. They, in fact, asserted their right to worship the Niyamgiri hill, which was to yield the aluminium ore.

This was just one among many instances where people participated in decision-making about what can, and can't, affect their environment.

It's important to assess the ecological impact of any project. Public hearings are a big step in the process

With green clearances treated as a hurdle on the long road to industrialisation, public hearings seem to be coming under wheels.

A recent example is of the Kondhs themselves. One of their contentions was about a refinery that was to convert the bauxite into one million tonnes of aluminium every year.

But on 23 July, the refinery - which is now supposed to be sourcing the bauxite ore from elsewhere - got environmental clearance to produce six million tonnes of aluminium per year.

This came despite an uproar in the public hearing of the project, which was conducted on 30 July 2014.

As per several accounts, a few hundred villagers stormed into the hearing, as many were not informed about the hearing until just that morning.

They opposed the project on the basis of a report that said bauxite for the mine would come from 3.7 kilometres away from the refinery - which the locals claim indicates the Niyamgiri hill.

However, the minutes of the public hearing uploaded on the ministry's website played down these concerns; some of these questions were listed as "other concerns".

Recently, Business Standard reported that the environment ministry has allowed work on the Polavaram dam in Andhra Pradesh without completing the mandatory public hearings.

People's right to question

This is not new - even the UPA government was known to exempt particular projects from public hearings, which can hasten the process by at least a month. But recent moves indicate that the present government wants to do away with the hearings altogether.

When a project applies for a green approval, it first receives an outline of the impacts it should analyse. The company gets this analysis (called the Environmental Impact Assessment or EIA) done from a consultant.

This is where the public comes in. Once the analysis is complete, the state pollution control board conducts a public hearing, where the EIA report can be debated and even corrected.

That aside, people can question the project itself, and also raise other concerns - such as the Kondhs' objection on the grounds that the project will destroy a hill sacred to them.

But over the last year, the ministry has amended the EIA notification to exempt public hearing for several projects.

Amending the rules

Most significantly, on 3 February, the environment ministry amended the rules to exempt 'linear projects' from public hearing in states that have an international border. 'Linear' projects are roads, pipelines and highways.

In one stroke, the people of 17 states - basically all states north of Madhya Pradesh - lost the right to question road or pipeline projects that affected their livelihoods.

Last December, the ministry extended the exemption to projects in industrial parks and estates. This 'clarification', the order said, was a result of representations from Industry associations.

Interestingly, this amendment itself was not subject to public comments, since it was put out as an interpretation of existing rules rather than a change in them.

In other cases, such as the Shivaji Memorial project off the coast of Mumbai, the ministry agreed to the Maharashtra government's request for exemption from public hearing on the grounds of public interest, without any objections.

This was despite the EIA clearly describing a 'major' impact on the fishermen of Mumbai, and on the air pollution, water supply and solid waste management in South Mumbai.

The ministry even amended the rules for coastal clearances to give the Central government the power to exempt all such memorial projects coming up in the sea from public hearings.

Also read: How Shivaji Memorial was cleared in 19 days despite environmental concerns

Such amendments have faced resistance from within the government. In March, the environment ministry excluded gram sabhas of scheduled forest areas from participating in public hearings. This conflicted with the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution (which provides rules on the diversion of tribal land), according to the government's own Tribal Affairs ministry, which had to step in.

It wrote a strong response to the environment ministry, outlining how the new amendment also contradicted forest dwellers' rights under the Forest Rights Act, 2006.

How public hearings help

A public hearing gives an opportunity for people to collectively voice their concerns and push for changes to the project.

Sometimes the issues include impacts not covered by the EIA. This is crucial, since the assessments are commissioned by those proposing a project. There is an inherent incentive for the agency to underrate impact or provide insufficient solutions to combat these.

"Public hearing is not a mere formality. Often the population has a better idea about the native implications of a project than government agencies and experts exercising their judgement from outside," says Godfrey Pimenta, an environmental lawyer in Mumbai.

"Agencies may turn a blind eye, even to harmful implications, and the hearing in a public court gives an opportunity, though limited, to highlight such consequences. Above all, the affected population has a right to be informed about any project which is likely to influence its quality of life."

Doing away with public hearings can cut the process of obtaining environmental clearance by over a month

Mistakes in the assessments also arise from not noticing seasonal professions, or activities of nomadic groups.

Fishing groups such as the South Indian Federation of Fishermen Societies have often highlighted how seasonal fishing is excluded in impact assessments. If the study is conducted in the off season, there are chances of the EIA missing the potential impact. The only way this can be remedied is in a public hearing.

A glaring example was that of the Kandla Port project, where the public hearing uncovered many holes in the EIA. People said that pollution in the soil was making it difficult for traditional potters in Tuna village to continue their work.

Some also raised the issue that the assessment excluded a large number of fishermen from its study. According to the meeting minutes, the government representatives admitted that this is a problem and promised to correct the study.

The future looks bleak

A committee constituted by the NDA government to review all environment-related acts took a dim view of public hearings.

In its report, submitted in November, the committee (headed by former cabinet secretary TSR Subramanian) recommended that public hearings under the EIA notification "may be dispensed" in industrial areas. The reason was that these areas are already under pollution regulations.

It has long been the government's argument that industrial parks, which have already received environmental clearances with public hearing, do not need another for establishing an industry within the park.

Experts argued that such a rule can sweep existing violations under the carpet.

"In industrial areas, there are grievances related to non-compliance of such regulations, especially if the project is related to the expansion of an existing industry," says Kanchi Kohli, legal research director at the Centre for Policy Research-Namati Environmental Justice Program.

The committee also recommended that public hearings are not necessary where human settlements are far away from project sites.

But it's not necessary that environmental impact is felt only near a polluting industry. Viewing human impact relative to settlements also ignores that such areas may be used for grazing, or drying fish, Kohli argued.

"In a dam, the impact may be further downstream. If a project is causing coastal erosion, there could be impact inland. Larger environmental impacts have to be considered, irrespective of settlements," she said.

According to some reports, the government is planning to act on the committee's reports to amend laws in the next few months. It may choose to not consider these recommendations, but its actions so far indicate otherwise.

First published: 2 August 2015, 4:18 IST

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)