Meet Tsering - 'Shepherdess of Ice', and subject of an award winning documentary

The auditorium was just a tad bit cold. No air-conditioner, of course. Nestled uphill from Macleodganj in Kangra district, the Tibetan Children's Village auditorium saw a packed house witness the solitary journey of Tsering, a shepherdess in the harsh reaches of the upper Himalayas. The film screening was part of the Dharamshala International Film Festival 2016. As the audience shifted in their seats and a few complained about the cold (about 8 degrees), the screen came alive with the directorial efforts of Stanzin Dorjai who shot the film in temperatures close to thirty degrees below zero.

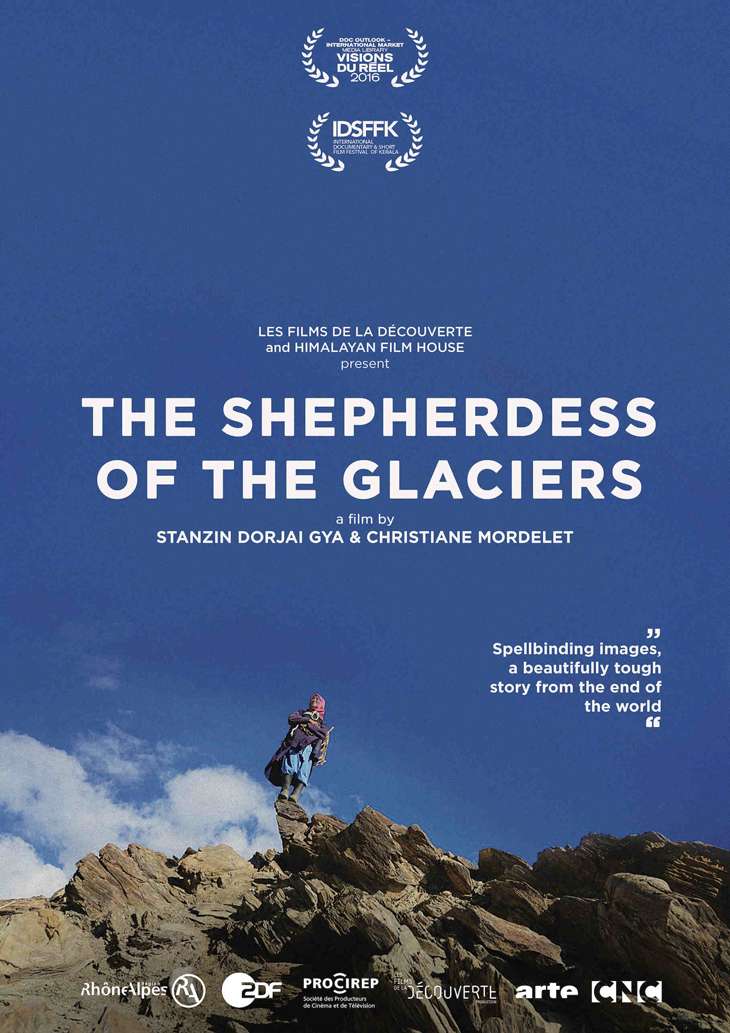

Dorjai's film, Shepherdess of Ice, traces the life of his sister Tsering, a traditional shepherd - amongst the very few that remain right now as the community faces rapid oblivion in the face of the usual forces of urbanisation. The film has just been awarded the Grand Prize at the 2016 Banff Mountain Film and Book Festival, and it's also won the Special Jury Mention award at the International Documentary and Short Film Festival of Kerala this year.

Tsering's journey, as she grazes her flock of 300-odd sheep and Pashmina goats on the 5,500-metre-high Himalayan plateaus, has been captured in all its stunning landscape brilliance, expected with a backdrop like Ladakh. What's even more stunning though, is the way the film has managed to capture the tremendous willpower that keeps an individual going in such circumstances.

The Ladakhi landscape is beautiful yes, but haunting as well. The massive cliffs around you, shorn of the exotic tourist-y lens can be a terrifying spectacle. The film manages to showcase this well, and locates the life of its protagonist within it equally well. The other area where the film manages to succeed is to depict the relationship between man and nature, or rather, in this case, woman and nature. The sequences where Tsering tends to her flock, with all their offspring, especially the scenes where she cries as some calves die in the brutal conditions and exults as new ones are born, are quite nicely done.

In an interview with Catch, Dorjai talks about the challenges he faced as a filmmaker shooting in such extreme conditions, how he dreams of a future where modernity and traditional occupations can co-exist, and the importance of sticking to one's roots.

AA: How was childhood like for you and did you accompany your sister on her shepherding journeys when you were young?

SD: I was born in Gia village in Ladakh. A lot of people called me Stanzin Gia for that reason, it's because I wanted my village to be a part of my name.

Till about 13, I was also a shepherd in the high mountains. In fact, till then I hadn't even seen a TV in my life, let alone have filmmaking aspirations! It's only when I joined Students Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh (SECMOL), around the time I was in high school, that I got scope to record and shoot little projects. That helped cultivate an interest in filmmaking. With SECMOL's help, I managed to finish my education from Jammu University, and eventually I started making full length feature films as well, locally based.

AA: There's some irony between the 'modern' equipment you used to capture the 'traditional' equipment your sister has - which is basically a stick and a basket!

SD: Well, she knows how to use her humble stick very well! It's been her companion for thirty years now. In the film I wanted to showcase the reality of her hardship and what it means to her. The stick and the basket she carries are all the tools she has. Through the film I wanted to show the simplicity of things that surround her.

During filming once, I fell down a slope with my camera. She didn't jump to save me but the camera instead! She said that she knows what impact can result from the kind of fall people can have on these slopes and my fall wasn't something major, and that I wouldn't die. But the camera might break, and I wouldn't be able to do what I came to do.

AA: How long did it take to shoot?

SD: The film took more than 3 years to finish. The problem wasn't so much shooting related but getting to her in the first place. First I had to reach from Leh to my village by car. Then from there on horseback for a distance. And then finally, trek a little distance as well with all the supply and provisions. A 3-day shoot would end up taking ten days.

AA: There are a lot of long shots and aerial shots in the film. How did you manage that?

SD: I'd have to plan all the shots with my sister Tsering. I'd tell her that I wanted her to come through a certain valley and to get that shot I'd have to be on top of a suitably placed mountain myself! So for the aerial shots, for example, each morning I'd wake up around 3 AM and walk up a mountain slope with the tripod and set everything up. She came later on around 8 AM and I used to shoot in that manner to get the shots I wanted.

Temperatures would plummet to -32 degrees and there'd be strong winds. In autumn I had a small crew but mostly, in winter, I was by myself. The shots were mostly in the Gia Meru valley.

AA: What are the technical difficulties you faced in such conditions?

SD: The extreme temperatures used to randomly crack the plastic buttons on the camera body. I had to keep at least 7 batteries charged at any given point of time. Each evening I had to keep the batteries inside my pockets and then get into the sleeping bag to ensure it doesn't freeze over. If the battery hits the cold ground, that's pretty much gone. Preserving the batteries and making sure the technology I had works was a bigger challenge than physical resilience.

AA: What did you do for food?

SD: I used to mostly have tsampa (made by lightly roasting barley) or anything my sister made. It's not obviously the most ideal dish, and if you're not used to it, then it can be difficult!

AA: Where do you see as the future of such a profession as this?

SD: We have to definitely welcome modernisation but in a good way, by also preserving traditional ways of life. There's a perception issue as well which needs to change. People look at shepherds and think they aren't aware of anything useful when it obviously isn't true. They have a great amount of knowledge about their work which is supremely difficult. I want to show their work to be as deserving a talking point as other professions. Those who work in multinationals say they are proud of their work, the same pride should exist for these professions as well. They just aren't given enough opportunities to showcase their worth.

AA: So how do you change that?

SD: Well, I've been telling every household in my village, which has about 80 homes, to make one pair of socks from the wool they have. When I go abroad to Europe or other places, I sell the same socks and get the money back to the village. This not only gets the money back to the deserving but there's a realisation of their own potential as a community, which is more important.

AA: How has your perception of what's modern and ancient changed during the course of the making of this film?

SD: I used to think I want great equipment and a bike when I was much younger! Once I achieved a bit of success as a filmmaker and got all those things, travelled across countries, I realised that what I want is the strength one gets - the strength I too had received - as a young boy in the Himalayas. It's very important to not forget one's roots. The flashy life comes with its own baggage, as does the life of a shepherd. But somewhere there's got to be a balance, it can't be tilted completely on one side.

AA: Has your sister seen the film?

SD: The first place I always screen my films is in my village. I've always had a premier screening at my village with the locals before taking it outside into the bigger world, so to speak. This film too, I watched back home with my sister. It was an amazing experience watching the film with her. She was hiding her face throughout the screening, and she did cry a few times, but she was pleased and happy.

Also Reads -

6 short films you can't miss at the Dharamshala International Film Festival 2016

Sonita Alizadeh and how rap music drowned the noise of Taliban bullets

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)