The Ministry of Utmost Happiness review: A one-dimensional story told in sterling prose

We waited 20 years for this. The Ministry of Utmost Happiness looks like a tome, feels like an epitaph, and seems to be born out of a pregnancy that author-activist Arundhati Roy didn't quite want. It feels like a creature expelled from the body, covered in uterine slime and blood, premature – simply because despite the obscenely long gestation period, it doesn't seem like a finished thought.

The book has received a plethora of mixed reviews, but whether these leaned towards the good or the bad, the book has been flying off shelves, and is a coveted picture-subject on social media.

Whether everybody actually reads it or not, every body wants to be seen reading it.

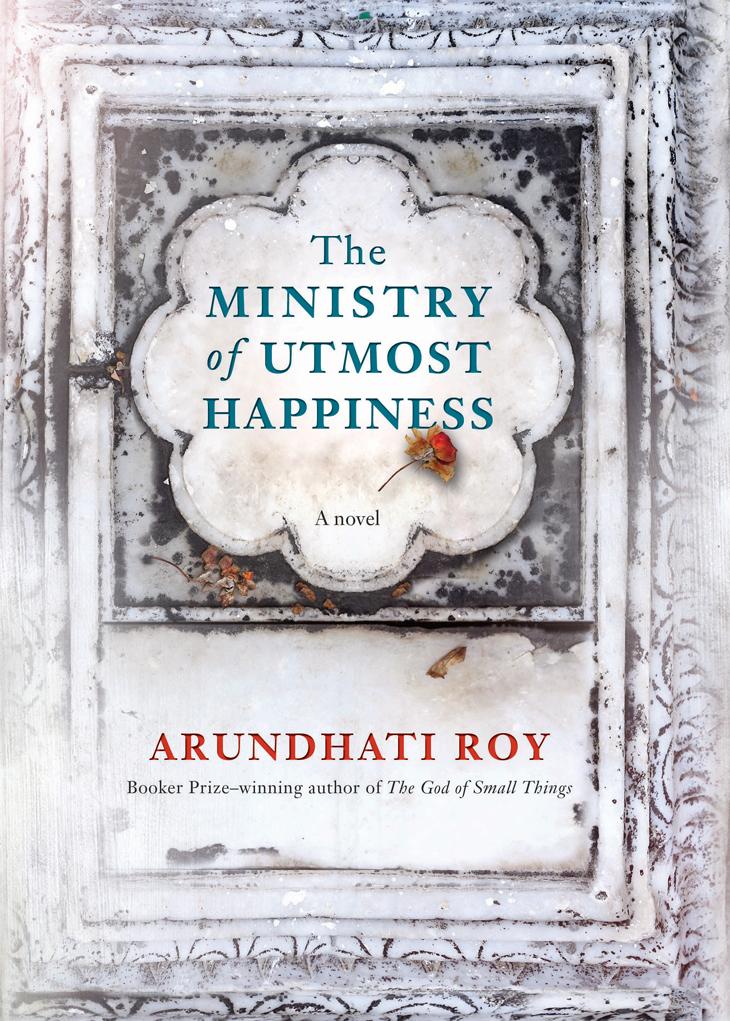

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness is not an easy book to read. It weighs you down. A feeling that is rather poetic because the cover is designed like a tomb, replete with wilted rose petals.

This is the tombstone of Kashmir, of the Maoists, of those who live under the flyovers and graveyards, of India– one that Roy has crafted with her spectacular turn of phrase.

Every page takes you deeper and deeper into a space where you are acutely aware of what the author wants to talk about, but the whole time you are left wondering – will she EVER talk about anything else?

Perhaps that is the problem with The Ministry of Utmost Happiness.

Despite a handful of shining characters running through the length and breadth of the novel, the bigger story, however, seems sadly unidimensional. Kashmir is pretty much all there is to it.

In The Ministry..., the activist wields the thought and the writer only the pen. And this is a burden Roy has chosen to shoulder. Despite the beauty of the words that appear, the story feels like a forced attempt to mark off the how-to-be-a-good-activist checklist.

Hijras and the bane of the other sex. Check.

Maoists. Check.

Kashmir. Check, check and check.

This is also where we agree whole-heartedly with many reviews of the novel that find fault with it for being more of an activist handbook rather than a purely literary one.

Roy plays with subtleties, and she plays deftly. The book begins and ends in a graveyard, which feels perfect. The story of a country simmering with hate in certain parts, packed in with earth and dead flowers between the front and the back cover.

The characters are light, in fact, they're sometimes far too simple. Anjum the hijra, Tilo the architect-turned-activist, Musa the militant, Amrik Singh the 'Butcher of Kashmir'...the list goes on. They flit in and flit out with thoughts and feelings that develop around predictable trajectories and remain like scratches on the grave rather than an engraving.

Others like Zainab, Saddam Hussain, Naga, and Dr Azad Bhartiya are strictly one-dimensional.

The only character with some extra meat is Biplab Dasgupta. But, as he tells himself – “Boys who've lost one eye are back on the street, prepared to risk the other. What do you do with that kind of fury?” – you know you have lost him to the predictability as well.

The Ministry... haunts you because you wish, deep in your bones, that there was something more. Something else you could sink your teeth into and ruminate on as the blood floods your mouth. Something else, something besides Roy's pet issues.

But then you are torn as well. What if this constant reiteration of India's festering wounds – the rapes and the riots, the fires and the pellet guns, those innumerable graves in the Valley and in the forests of Bastar – is about something else entirely?

What if it is about stripping the stories down to their bare minimum, and throwing the facts in your face like those bodies are thrown in the fire or the grave?

What if it is to batter you into numbness with the horrors, so that when you come to your senses, the trauma is ingrained you. Much like Anjum's botched up sex-change operation.

“The surgery was difficult, the recovery even more so, but in the end it came as a relief. Anjum felt as though a fog had lifted from her blood and she could finally think clearly. Dr Mukhtar's vagina, however, turned out to be a scam.”

You can no longer undo it. You no longer know which side to pick, you are exhausted, but you know which side the scales tilt. Uncomfortably.

Perhaps this is what Roy wanted to do.

If this was Roy's intention then The Ministry... hits strikes an obscure but disturbing chord.

“One day Kashmir will make India self-destruct in the same way. You may have blinded all of us, every one of us, with your pellet guns by then. But you will still have eyes to see what you have done to us. You're not destroying us. You are constructing us. It's yourselves that you are destroying. Khuda Hafiz...”

And this is one area that The Ministry... aces. The language.

It is faultless. It flows like magic over the rough, shoddy terrains of the country, narrating horrors in charming sentences. Take this for example:

“...she had learned from experience that Need was a warehouse that could accommodate a considerable amount of cruelty.”

With the story of India traced to the point of Gujarat's Lalla, ruling with his saffron parakeets as the chamars revolt, the pellets blind, and mutton in the fridge kill. The Ministry... lives on like the malls built on graves.

Should you read this book?

Someone had asked me if he should read the book, and if he could underline favourite sentences like he does with most books he reads – yes, I had said, you can probably underline the whole book. But that is only to be expected from a writer of Roy's calibre.

The real test of The Ministry..., though, was always going to be the story. And, on this front, there's not much besides some loose kite strings, tangled in mid-air, accidentally strangling a crow.

First published: 20 June 2017, 16:41 IST

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)