Tales of temples & pangs of partition: meet Pakistani writer duo Anam & Haroon

Anam Zakaria and Haroon Khalid are a couple. That theirs is a marriage of the mind and the heart is evident from the kind of books the two have been churning out almost every other year from Pakistan.

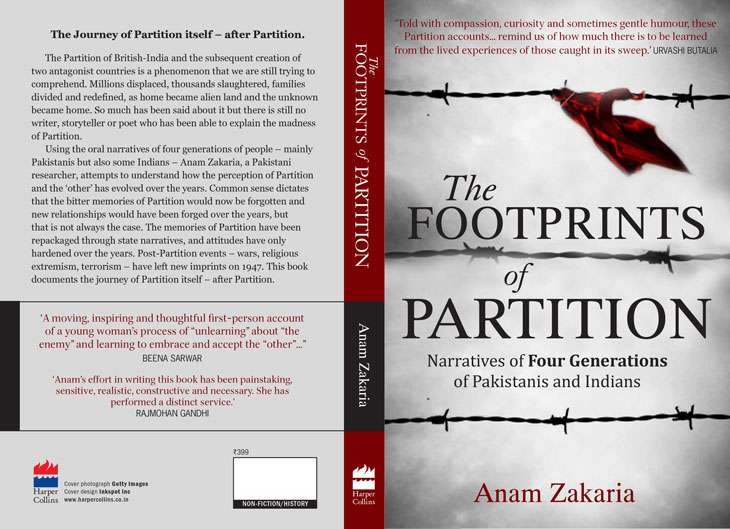

Anam's first book Footprints of Partition explored how the narrative of Partition has evolved over the years. She interviewed Indians and Pakistanis across four generations to understand how the newer generations remembered and understood the events around 1947.

Her next book - out this year - "explores the impact of the Kashmir conflict on the villagers living across the Line of Control in Pakistan Administered Kashmir (PoK)".

"The book attempts to understand what freedom and peace mean to Kashmiris popularly believed to be living in an Azad Kashmir," says Anam.

Haroon's first book A White Trail was an account of Pakistan's religious minorities, who have culturally assimilated into the Islamic Republic, often taking on Muslim names in a hope to survive and thrive post-1947.

Khalid's journey into the heart of Pakistan's religious minorities took him to the gurdwaras, the churches, and the temples - most of which are in ruins - thanks to the post-Partition riots and later as revenge for the demolition of Babri mosque in Ayodhya in 1992. The journey to document their religious beliefs and folk tales wasn't easy for Khalid.

The biggest challenge, as he writes in his introductory note, "was the constant fear in the minds of the minorities, which would lead to self-imposed restrictions when responding to slightly 'controversial' questions..."

His second book In Search of Shiva was a study of folk religious practices in Pakistan. Though 11 essays Haroon took his readers on a tour of the shrines in central Pakistan - and not necessarily Shiva temples - as the title of the book suggests.

Haroon's newest, Walking with Nanak published last November is a fictionalised depiction of Nanak's relationship with his Muslim companion Bhai Mardana. The book also details his journey to Nanak's shrines scattered around the country and traces the history of how the unorganised spiritual movement of Nanak took the form of an institutional religion.

Anam and Haroon talk to Catch about how they met while working on the Citizens' Archives Project, how they travelled and conducted interviews together and how they shape each other's work.

Edited excerpts:

LH: Anam, how did you get involved in the Citizens' Archives Project? Did your family migrate from India? Did you grow up hearing stories about Partition?

AZ: I joined The Citizens Archive of Pakistan (CAP) when I returned from Canada in 2010. I was immediately struck by the oral history project, which offered insights into alternative historical narratives that I was largely unfamiliar with.

My father's family migrated from Batala in India while my mother's family was based in Lahore at the time of Partition. Living in Punjab, Partition narratives did not escape me. I grew up hearing tales of refugee camps, massacred bodies and bloodshed from my maternal grandmother who was a volunteer at the Lahore Walton Camp.

School textbooks further reiterated one-sided stories of violence. While many of the interviews I conducted at CAP reinforced these narratives, I began to understand that history is not linear nor black or white. Underneath the mainstream state narratives lie personal experiences, full of contradictions and nuances, that need to be appreciated if one is to try and explore Partition.

LH: Did you have to fight the urge to not write such a book and move on?

AZ: I don't think one can ever 'move on' from historical events that shape our identity. In fact, to move on is to create a vacuum, which can be usurped by hardline elements. It is essential to embrace and explore one's history to have a better understanding of one's present self.

LH: What is the focus of Footprints of Partition? Did it help you see the 'Other' in a different light?

AZ: The book uses interviews of four generations of Pakistanis and Indians to explore how the narrative of Partition has evolved over the years. The oldest person I interviewed was 112 years old while the youngest was nine.

While I was working with CAP, I led the Exchange-for-Change project, which connected school children in India and Pakistan. I witnessed the biases, hostility and stereotypes rampant on both sides of the border and began to realise that there was a disconnect between Partition survivors and the later generations in how they remembered and understood the events of 1947.

The book is a quest to understand how that disconnect has arisen in a country fortunate enough to still have its first generation around as walking talking sources of history.

In Pakistan, where minorities are restricted to a mere 3% of the population, Hindus and Sikhs often become figments of the imagination, an imagination fueled by media propaganda and mainstream prejudices. Speaking to Partition survivors, I heard stories and tales of a time when the 'other' wasn't really the 'other' but rather an integral part of the community. As a third generation Pakistani, these interviews helped challenge many of my own stereotypes.

LH: Given the blow-hot, blow-cold attitudes between our two countries what do you think should be the way forward? Can we ever be friends? How do such projects help?

AZ: The relationship between the two countries and the resulting state narratives certainly have an impact on people-to-people relationships. It is thus all the more essential to open contact between ordinary Indians and Pakistanis so they can sift through the jingoistic macro narratives to explore the 'other.'

LH: According to a USCIRF report, Pakistani textbooks are peppered with lies such as "...in the Hindu religion widows are deprived of their basic rights to live as they are burned alive with the ashes of their husband's dead body" or "India also blocked Pakistan's assets so that the country was weakened financially; and it also stopped the flow of weapons so that the newly established state remained fragile in defense". How do we change this?

AZ: Textbook biases pose an enormous obstacle in promoting peace between the two countries. Pakistani textbooks are rife with hostility against Hindus. Crucial historical omissions in Indian textbooks and frequent portrayal of Muslims as barbaric and savage further sow the seeds of hostility in the young generations. Textbooks on both sides of the border require serious review and revision, especially since teachers also study from similar resources and form hardline attitudes that are transmitted from one generation to the next.

LH: Haroon, a lot has changed since you wrote A White Trail? Pakistan is even more intolerant about its minorities...

HK: I don't think a lot has changed since the publication of my book. The goal of the book was not to document any particular time period but rather present the reader with a vast framework through which different minority communities in Pakistan can be viewed. In most of these cases, there are certain patterns that have been identified and it is those same patterns that are playing out again. The names and locations change but the issues remain the same.

LH: In Search of Shiva' is a brave effort. What does it take to write such a book, to document the intolerance...

HK: In Search of Shiva is not just a book that documents the existence of intolerance in Pakistan but rather is a depiction of a living culture, which incorporates elements of both tolerance and intolerance. It is these contradictions that I was interested in and that I attempted to present, of how tolerance can exist within intolerance and vice versa.

LH: Did Haroon and you meet after you started working with CAP? Does the common interest in India/subcontinent solidify your bond?

AZ: We were colleagues at CAP, where Haroon was heading the Minority Project that led to his first book, A White Trail, and I was leading the Oral History and Exchange-for-Change project which led to my first book, Footprints of Partition.

We travelled and conducted several of the interviews together and played a key role in shaping each other's work. As opposite genders, researching together enables us to access spaces which would otherwise be closed off, hence adding depth to our work. Given our particular interests in the subcontinent and its history, we are also able to add a unique perspective to each other's work, providing critical feedback.

First published: 2 January 2017, 9:21 IST

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)