Rushdie Returns: what to expect when his new book hits shelves tomorrow

A man by the name of Ibn Rushd, (a rationalist philosopher known to have lived in Islamic Spain in the early decades of the second millennium) is seduced by a 16-year-old girl in need of a home.

Her name is Dunia, which means world.

Ibn Rushd takes her in, as a homemaker and lover, and proceeds to have sex with her. A lot. Like, a lot. Their furious sexuality bears fruit, and the young Dunia has dozens of children.

But it's a Rushdie book, so you can hardly expect banal details such as how many children she actually had. Suffice to know there were many.

Jump 2000 years.

The descendants of Dunia and Rushd are scattered across the globe. But here's the catch - Dunia was in fact a jinn in the garb of a human (just so she could fornicate the way humans do). As a consequence, her descendants, too, have jinn-like powers.

One descendant can levitate a few inches above the ground; another, shoot lightning from her fingertips; a third can detect when someone is lying in her presence and make said liar's body rot spontaneously.

If this sounds to you like a rehash of X-Men, you're likely not alone.

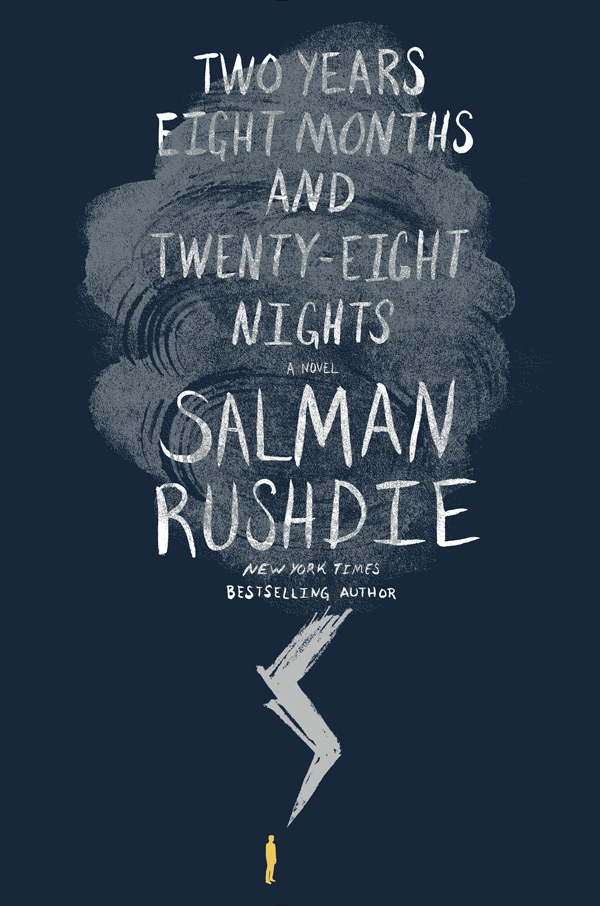

This is the premise of Salman Rushdie's new novel Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights. Or, what is essentially a (contrived? Verbose?) manner of saying 1001 Nights.

Rushdie's 'Ibn Rushd' appears to be styled in his own self-image

Salman Rushdie's father had adopted the family last name as a tribute to the rationalist philosopher, Ibn Rushd.

Rushd, also known in Western history as Aerroes, lived in the Islamic Caliphate of the 12th century. He was eventually banished from the kingdom by the orthodox king Yakub-Al-Mansur, who did not take kindly to Rushd's rationalist writings.

Rushd's books were burnt, his ideology mercilessly attacked, and he lived in exile for most of his life - till he returned to the Caliphate a year before his death in 1197 AD.

It's not surprising that Ibn Rushd weighed heavily on Rushdie's imagination - his life has almost eerily mirrored that of the man for whom he was named.

His Satanic Verses was declared blasphemous. Banned. Burned.

He may not have been banished by decree but he certainly was by circumstance when he spent the next seven years living under police protection.

Reviews of Rushdie's book, his first adult novel in seven years, have been disappointing

Small wonder then that at some point, he referred to Rushdie as a 'worthy name' to take on freedom of speech.

And in a series of meta-references to history in his new book, Rushd argues that his children should bear their mother's name and not his own. Rushd tells Dunia, "'It is better that they be the Duniazat, 'a name which contains the world and has not been judged by it. To be the Rushd would send them into history with a mark upon their brow'."

For all that, early reviews suggest the book is burdened by the history it does not tell, rather than the one it does.

Rushdie's 2015 reception

Reviews of the book, his first adult novel in seven years, (the last time he took a hiatus as long was after the Satanic Verses), have been disappointing.

With characters too complex and a story too elaborate, The Standard said that Two Years, Eight months and Twenty Eight Days "lacked human involvement".

"With its italicised passages of Islamic jinn lore and multiplicity of stories each contained within another like a 'Chinese box', the novel is of great formal brilliance but ultimately it's a mere pomp of words."

The Guardian argued that the parallels were simply too literal. Especially when the bad guys are "executioner jinn parasites stoning women to death" and "suicide-bomber jinn parasites".

Rushdie even seems to make the argument that the reason the bad guys do what they do is simply that they aren't having enough fun in bed. "When hopeless young men were provided with loving, or at least desirous, or at the very least willing sexual partners, they lost interest in suicide belts, bombs and the virgins of heaven".

This sounds less like a nuanced argument tackling Islamic fundamentalism and more like a personal slight he would like to throw at someone who bullied him in school.

The Independent seems to concur. "Any sense of pleasure one might derive from Rushdie's indisputably freewheeling imagination is sabotaged by how little he appears to care for its fruits."

Perhaps fitting, then, that Mr Geronimo, a descendent of Dunia, skims the surface of the Earth four inches above the ground.

That, perhaps like another meta-reference within his book, aptly reflects how shallow Rushdie's latest literary dive really is.

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)