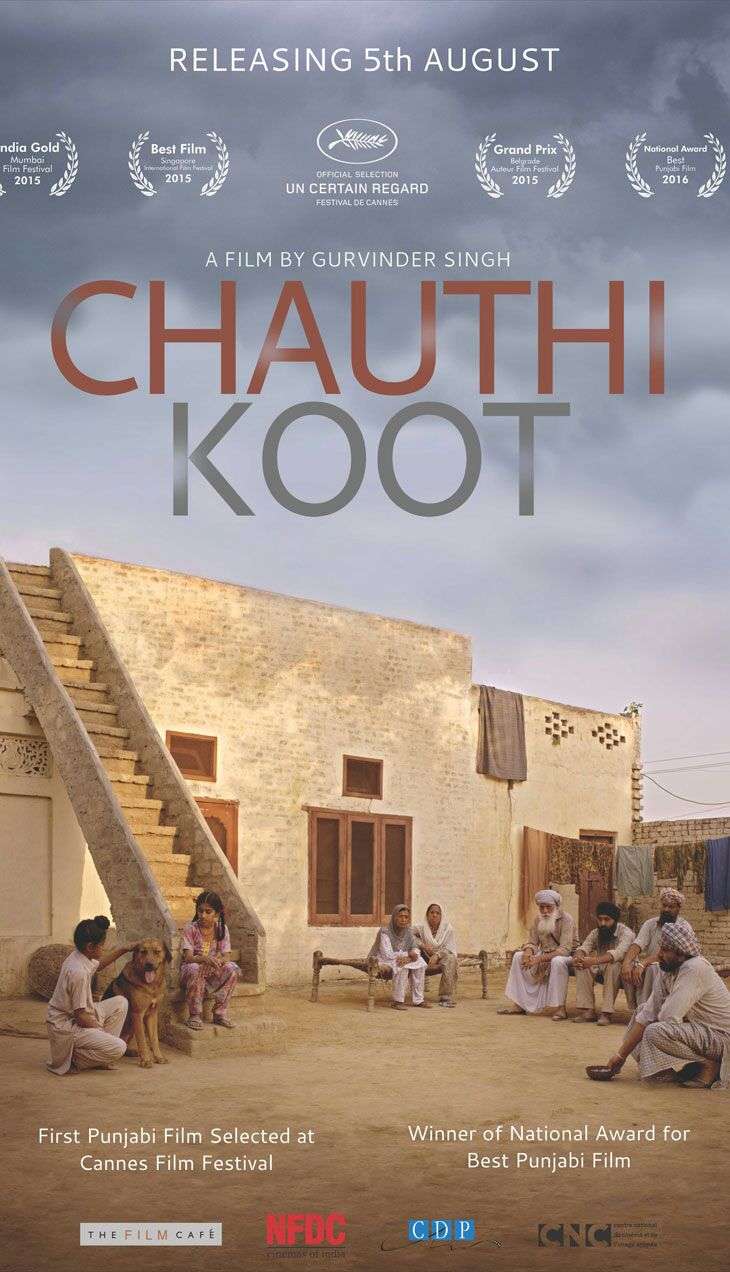

His first full length feature Anhe Ghore Da Daan (2011) bagged 3 national awards and a lot of international acclaim. Now, Gurvinder Singh\'s back with Chauthi Koot, which has already won a National award. It\'s also the first Punjabi-language film to premiere at the Cannes Film Festival.

Adapted from two short stories by author Waryam Singh Sandhu, Singh\'s latest feature uses the Sikh separatist movement as a taut backdrop to his visually evocative human narrative. Ahead of its India release (5 Aug), in an interview to Catch, Singh talks about the memories of militancy as a 10-yr-old child, travelling across rural Punjab with folk balladeers and why he\'s left the city for the hills, for good.

Since you weren't born in Punjab, how'd you manage to tap into the pulse of the state so vividly?

I travelled a lot. Besides, even though I wasn't born there, I was from a proper Sikh household. Plus, living in Delhi is almost like living in a mini Punjab, where religion and language were both omnipresent. Later, of course, I realised that the community I was immediately from had very different concerns from rural Punjab communities where the priorities were very different.

Also Read - Interview: Communal forces have hijacked the spirit of our constitution, says Anand Patwardhan

You travelled through Punjab between 2002 and 2006 with a lot of folk artists. How has that experience informed your aesthetic?

Yes, for four years I was travelling rural Punjab documenting ballads on a grant from India Foundation for the Arts. You're in a mela one day, a dargah the next - observing people. The most shocking thing for me was the syncretic tradition. At the dargah, you would have Sikhs and Hindus coming in. I saw a lot of folk religion and intermingling of faith, which can be a bit of a revelation.

I was travelling mostly with performers from the so-called lower classes - dalits, mazhabis, valmikis, low caste Muslims and saw the social dynamics. How the Jat Sikhs dominate land and, in fact, the villages had two gurudwaras - one for the Jat Sikhs and the other for Mazhabi Sikhs.

That shocked you?

Well, one has all these ideals in mind of a caste-less religion for Sikhism. All those myths were shattered because you could see the reality was something else. You could see up close things like the agrarian crisis and its actual impact, how so many of the moneyed Jat boys were aimless and ending up doing drugs.

I was living with these people, eating and drinking with them, trying to understand their angst and their alienation within mainstream religion and politics. All this, in fact, became the foundation for Anhe Ghore Da Daan, because if I didn't know this class, that film wouldn't be possible.

You also made a feature called Pala based on your travels?

Pala was about a man who sang qissas. The film revolved around documenting folk traditions during my travels based on this one man's experiences. For example, popular qissas included Heer Ranjha, Mirza Sahiba and Sassi Punnun. Most have originated within Punjab but some have Arabic origins. Some are even traced to Rajasthan.

Then there are folk gods like Gugga Peer, which is like a snake god for the lower classes, with shrines across a lot of places in Punjab. Or Sakhi Sarwar, also known as Lakhdaata Peer.

So Pala was a man who sang all these qissas. He couldn't read or write but it was a tradition he learned orally from his elders. Pala was, in truth, one of the first people I met during my travels in Punjab.

How was your association with Mani Kaul like? Have you been particularly influenced in any way by him?

Yes, when I came to know him I found a lot of similarity in the way both of us looked at things - thematically or in images for a film. So yes, I shared a strong association. Especially the quality of abstraction in his films which I have always cherished.

I myself haven't been fond of things which are too clearly explained or expressed in words. And here was a man making films which were more about the feeling and experiences than anything else. Films which can be seen again and again, yet experienced differently.

I used to focus on things like composition or laid emphasis on images, for example. Once I started to be with him, I realised one has to be like a musician. Someone who's working in time, not in the visual space.

What gave you the idea to develop Chauthi Koot?

I read the original story of Chauthi Koot, around the same time Anhe ended. Also, when these events - the militancy - were actually happening in the 80s I was about 10. I remembered listening to stories from parents, the news and, when Indira Gandhi was assassinated we were locked in our house for 10 days.

I could see mobs roaming the streets and local gurudwaras being burnt. Those memories of looking through the curtains at what was happening outside stayed with me. I suppose these memories lie dormant and one never knows what triggers them. I suppose it was there in the backyard of my memories somehow, which made me want to make a film on it.

You had a very personal premise for the film.

I felt a great parallel to give the film a bit of perspective. Between myself as a kid in Delhi, locked up in the house during times of insurgency, and those people in a remote farmhouse in rural Punjab, where anyone can come in and demand anything of you, there's no security.

You spend a lot of time on locations apparently...

First, I always look for locations. Even before I write the script, I scout for the location. That's the first casting for my films. The farmhouse in my film is a crucial character, so is the train and the station. They give me an idea of how to stage movement, how the action will unfold, who enters and exits from where, how the camera moves in relation to the characters - basically everything.

These have to be living, vibrant beings and not just backdrops to look at. It's that important. We were searching around for lots of houses for this film and we had the local patwari with us. He told us about this farmhouse, where the family lives in Australia, and only the caretaker lives there.

How'd you handle adaptations - is it easier to play around with a pre-defined premise?

The story is like a foundation on which you can build, add something or remove as you deem fit. Like sometimes certain dialogues in a text are so perfect, the way it's written or the tonality - that I retain those lines, because they're so beautiful. But certain places you need to improvise where the characters need to come up with their own unique dialogues. So sometimes I stick completely to the script, sometimes I deviate.

You've used a lot of non-professional actors too...

For every role I'm open to looking at both. In this film, for the role of Joginder, I knew I wanted a professional actor. Because the role demanded a certain body play and exertion. But other roles can, of course, be carried off by non-actors.

There are a lot of non-actors in this film. When the film begins there are two men running in the station and a Sikh man who boards the train with them. in fact, most of the characters in the train are 'non-actors'. However, at the farmhouse, the three major characters are professional actors.

How'd you get 'non-actors' to shed their inhibitions?

When I select someone I know they won't have any inhibitions. I just tell them to play themselves. I do recognise that they may not have the skills to play someone else. Even if they did, it would ring false on the screen.

The dog Tommy plays a crucial role in the film. How'd you train him?

He's a Himalayan sheep dog, what they call a gaddi dog. We got him when he was 3-months-old. The trainer told us specifically that the dog needs to be at least 2 or 3 months to be able to train. In fact, Tommy became quite attached to the trainer and only then did we start filming.

Both the militants and the police have a problem with the dog in the film. Was this commonality intentional?

It's there in the story as well actually. The dog is a victim and everyone's trying to take their frustration out on him. The militants have a valid reason, because the dog keeps barking at night when they pass, alerting the forces. But for the police the dog is just an irritant. For them, the dog is an easy thing to kill without any repercussions.

Ambient sounds play an important part in your films. Even in Chauthi Koot there are long sequences of great visuals and sound with no dialogue - do you feel it can get too much for some viewers?

Let them feel alienated. Those who are interested will not feel alienated. My films aren't for insensitive people.

Artists will now be graded by the Culture ministry in order to showcase or promote their work...

It is absurd and ridiculous. No artist true to her/his vocation will subject herself or himself to this idiocy. How will they rate someone like, say, Arundhati Roy? She will not be in the waiting category also, she'll be an outcast. Outstanding category will be for people with right-wing ideology and who's soft on the government.

What's next for you? Since you paint, do you have plans on any exhibition?

I just finished a short film called Infiltrator. It's part of a ten-film omnibus by a Turkish production titled In the Same Garden. The omnibus will feature ten films from ten countries across the world. I do paint as well but there are no plans of an exhibition in the near future.

Also Read - Muzaffarnagar Baaqi Hai is a film that won't stay quiet

You went off to the hills in Himachal a while back. How'd that happen?

It's been a year and a half since I shifted to Bir. I've always wanted to leave the city and do a bit of farming. I was tired of living in boxes and apartments, and needed more space.

There are nine houses in the village where I stay. The best part is the house doesn't end when you step outside. All that space around you seems part of the house! That's the kind of living dignity every human should have. Right now it's become all about territory and possession. In the city you step outside and you're effectively outside the house. That's not the case in the hills.

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)