What connects Africa to Rajasthan? The Solar Mamas of Tilonia village

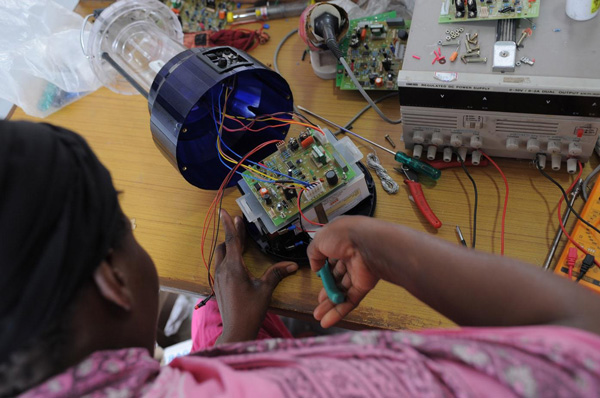

Some months ago when Kamla Devi, a semi-literate Tilonia resident and solar engineer was teaching a clutch of rural African women the intricacies of a charge controller, she didn't know of the soon-to-be-huge narrative of India Africa Forum summit.

She certainly didn't know the government's lofty Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC) commitments to the UN.

Yet, she's probably had a more direct, firsthand impact on the lives of African women than any number of pacts.

How? Barefoot College, the unlikely network between the women of Tilonia and Africa.

The college was born out of 70-year-old Sanjit 'Bunker' Roy's desire to look for a radically different medium of education that can address poverty by directly engaging with those most affected by it.

The opposite of top-down programmes, Roy's vision was a college that mirrored a Gandhian way of resolving problems: working ground up, empowering the very community whose lives he wanted to change.

He'd decided to work in remote India. In the late 60s he came across Tilonia, a small village in Ajmer district, Rajasthan. Roy convinced then collector of Ajmer, Anil Bordia, to help him lease an abandoned Tuberculosis Sanatorium premises from the Government at Re 1 a month.

And on that property Roy gave his vision shape.

"The idea for a proper college came in 1972. It's now the only solar electrified college in India. Everything works off the sun here," he says. "Here we believe more in practical knowledge than theoretical skills. And it's the only college that doesn't give any degrees or paper qualifications."

The college itself, spread over eight acres is entirely run on solar energy and maintained by in-house solar engineers - almost all of whom are women from Tilonia and nearby villages.

The women, once they finish training, become teachers to other incoming batches of women. That includes women from other countries, especially Africa, on a regular basis.

Photo: Bunker Roy

For a college whose vision is so understated, the results have been remarkable - close to 500 rural grandmothers have been trained to be solar engineers and approximately 20,000 houses in Africa have been solar electrified.

In Tilonia itself, 60 KW solar panels and five battery banks supplemented by 15 invertors power the college - all installed by local engineers. The only condition partner villages must adhere to: "They must pay for the maintenance of the solar units every month even if they can't pay for the equipment. This just makes the whole process sustainable."

Its success has ensured the government takes note - the Ministry of External Affairs has plans to set up five Barefoot Training Centres in Africa, as well as to solar electrify 11,000 more houses across 22 countries there.

Closer home, about 24 Barefoot Colleges have been set up across various towns and villages in India.

But beyond the big bland numbers lies the true impact of the college - and those are in the human stories it has changed forever.

Tilonia's bravehearts are its women

Kamla, who was married when she was three, struggled through night school and had to make do with candles, because there was no electricity at home - it cost too much.

She joined the first batch of women at the college in the 90s. "My mother-in-law and other villagers were not happy, they said a woman's job is to stay home or work the fields. That these kind of jobs need people with proper education," she says.

Photo: Bunker Roy

But her husband didn't mind and her father-in-law was supportive.

It was difficult. "All the names were in English and I could hardly follow what was meant by transistor or capacitor." But the empathetic trainers helped. "We were taught English first, and then the names of the equipment."

She learned the ropes, then took her learnings back and set up solar lanterns and units in nearby homes and schools. "I set up some solar units in my home for the first time in 1996 that could power four lamps," she remembers with pride. That's also when the villagers realised that "even semi-literate rural women can do the work of a qualified engineer given a chance."

Kamla started training other women from nearby towns in Ajmer as well and has been associated with the college as a trainer since.

The African connection

Hannah, who comes from Philippolis, a 40 sq km town in South Africa has been training since this August. She hopes to light up her village as well soon. "We do get some electricity but the cost is very high. I'd like to change that by learning how to put solar power to use instead."

How does she find the course? "I'm learning about charge controllers now and the way the battery works. I find it all very interesting!" says Hannah animatedly, betraying no sign of the challenges involved in learning a science from a trainer in a foreign land speaking a different language.

Photo: Bunker Roy

"My husband was quite hesitant initially," she admits, "but I managed to convince him it's alright and that I'll be in touch over the phone." His concern isn't unfounded. "I am the first one to leave my village and travel so far," she reveals.

Alida from Namibia is equally resolute. "I arrived this September," she says, but she's already picked up the basics and knows the names of the equipment. Hers is a familiar story: too poor to afford electricity, and the desire to change the lives of their families.

It's rather obvious, says Roy about why he chose Africa as the primary country to carry out his innovative model of community learning. "If you want to prove and challenge a barefoot model like the one we have, it should work under the most adverse conditions in the world. So if you can work it in Africa, you can work it in any lesser developed country south of the equator," he says.

Its success is hardly in doubt. "The government of India has asked us to set up six barefoot training colleges in Africa at the cost of $400,000 each," he says. They've identified Senegal, Burkina Faso, Liberia, South Sudan and Tanzania. "All the women from Africa are taught for six months as part of a residential programme, mostly through sign language," says Roy. "There's a feeling of solidarity despite the language gap."

Why senior women are the perfect medium for training

It's simple really, says Roy. "Men are untrainable, no? They're restless, ambitious, compulsively mobile, and they all want a certificate so they can look for a job in the city." The 'most visionary thing to do' is to select senior women, who command respect, are rooted in the soil, who won't suddenly leave. And importantly, who don't mind training other women. "A man will never train another man but a woman will. In fact all those women who've learnt the skills from the college have gone back to their homes in Africa and trained other women," he says.

Roy is generous in his praise for Tilonia's women, who've taken on huge odds to not just learn the craft but share their knowledge with their communities. But he has a special word of appreciation for Bhagabath Nandan, the "master trainer who trained the first lot of women in Tilonia."

Semi-literate African women take 20-hr flights, leave husbands and homes, to learn solar lighting in Rajasthan

Born in Harmara village, Ajmer, Nandan was involved with the educational programmes of a number of night schools in Tilonia.

Then in 1984, as luck would have it, a 145-watt solar unit was installed in his village, and he was given the responsibility of maintaining it. "I was really taken aback, I didn't have any idea about any electrical equipment. I didn't know even AC from DC. In fact there wasn't any electricity in my home to begin with!" laughs Nandan.

But the local supervisor insisted Nandan take up the job, so he did.

"I had to either figure out malfunctions myself or coordinate with engineers who came from Delhi to fix it. Slowly but steadily, I learnt from this experience," says Nandan, who joined the college in 1975 and has been with them since.

Funding was originally dependent on contributors from abroad sending money under the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA). Post 2008, though, the Indian government and UN bodies partnered with them to train women from across developing countries under the Indian Technical & Economic Cooperation Programme (ITEC). "We got money from UN Women, and from UNDP's small grants programme as well," says Roy.

The real heroes are these grandmothers

Ask what he finds most remarkable about this journey and Roy is clear: it's the courage of these women. "They can't read or write, but she's got phenomenal courage, this woman. Imagine someone who's never stepped out of her village, is barely literate, taking 20 hr long flights, changing airports, to arrive here to learn about solar power!"

The fears don't end there. "These grandmothers are under severe pressure. When they go abroad, their husbands say they can't wait for six months and will take another wife while they are gone. Despite such pressures, they come to India. And after they go back, they solar electrify their villages too." Their stories may not make headlines the way visiting heads of state do. But the real magic of the India-Africa story is in these handshakes that signal a commitment to sharing the sun and lighting up their own remote corners of the world.

More in our #IndiaAfrica summit coverage:

India can learn from Rwanda! Seriously?

Cut the noise. Here's what Ethiopia says about #IndiaAfrica

#IndiaAfricaSummit could be a game changer. Here's why

#IndiaAfrica: What Africa Expects Out of India

#IndiaAfricaSummit: Don't just stand, go in and deliver

#IndiaAfrica: India can learn from genocide-torn Rwanda's amazing progress

#IndiaAfrica is fine. But is our aid in solidarity or an instrument of control

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)