Shadow Lines: the drugs and terror track in Punjab

The danger

- Punjab has a major drug problem

- The addiction rate in the state is almost 70%

- There is also a massive Af-Pak heroin trade transiting through the state

- With the Gurdaspur attack, terror too has reared its head in Punjab after eight years

- The question to ask is: could the two be linked?

The magnitude

- The drug trade is used the world over to finance terror

- International reports prove drug networks are also used to move weapons and sometimes terrorists themselves

- In 2013, over 60% of heroin seized by the narcotics bureau in India was from Punjab

- In 2014-15, this jumped further: over 99% of heroin captured in India was seized in Punjab

The politics

- There is a dark nexus between traffickers, cops and politicians in Punjab

- Jagdish Singh Bhola, an ex-cop and drug trader, named Punjab minister BS Majithia as one of the masterminds of the trade

- Not much action has been taken on this

- Majithia\'s sister is Union minister Harsimrat Kaur Badal, daughter-in-law of Punjab CM Parkash Singh Badal

- Badal said terror is a national problem, not a state one

- He blames security forces for the porous border. Border Security Force troopers have indeed been caught dealing in drugs

- But the smuggling of Af-Pak heroin is allowed to flourish in his state unchecked

- This could well become a shadow route for smuggling in weapons as well

Update on 4 January 2016

Following on the Gurdaspur attack last year, there is an ongoing attack in Pathankot, suspected to be by Pakistan-backed Jaish terrorists. The attack points to porous borders and big intelligence failure. This Catch story from August 2015, on the possible overlaps between drug trade and terror routes had flagged a major fault line. The current attack brings this unaddressed issue back in focus.

***

Two urgent issues confront Punjab today. The question no one is asking loudly enough is: could the two be dangerously linked?

The first problem, most recently in the news, is terrorism.

This has come back to haunt the state after nearly eight years. But given the bloody history of the Punjab insurgency, the Gurdaspur terror strike of 27 July brings back frightening memories.

The attack took 10 lives - three terrorists, four policemen and three civilians. But it could have been far worse if live bombs had not been discovered by a passerby on rail tracks near Dinanagar, or if the wire attached to one of the pressure mines on the bombs hadn't come loose before one train ran over it. The passerby reportedly alerted a railway employee who halted other railway traffic just in time.

The open secret: Punjab's drug addiction

The second issue, which has been in the news for many years, is drug trafficking and addiction.

On 19 June, the Narcotics Control Bureau (NCB) stated Punjab had recorded 50% of the country's drug related cases.

Surveys from previous years have revealed equally shocking figures.

Last year, an NCB poll in eight cities throughout Punjab showed that four out of 10 men surveyed were addicted to drugs.

Another 2009 survey by the state's Department of Social Security said 67% of the state's rural households have at least one addict.

One 2010 report by the Gurdaspur Red Cross Drug De-addiction and Rehabilitation Centre, in fact, said 64% of the youth from Gurdaspur District were addicted to one 'intoxicant' or the other.

Unemployment, easy availability of drugs and the police nexus with drug smugglers and sellers were the key reasons cited.

Last year, ex-DSP Jagdish Singh Bhola - who is accused of running a massive synthetic drug racket and had confessed to funding political campaigns during the last state elections - named Bikram Singh Majithia as one of the key masterminds of the drug trade.

Punjab has 50% of the country's drug related cases. In Gurdaspur, the addiction rate is 64%

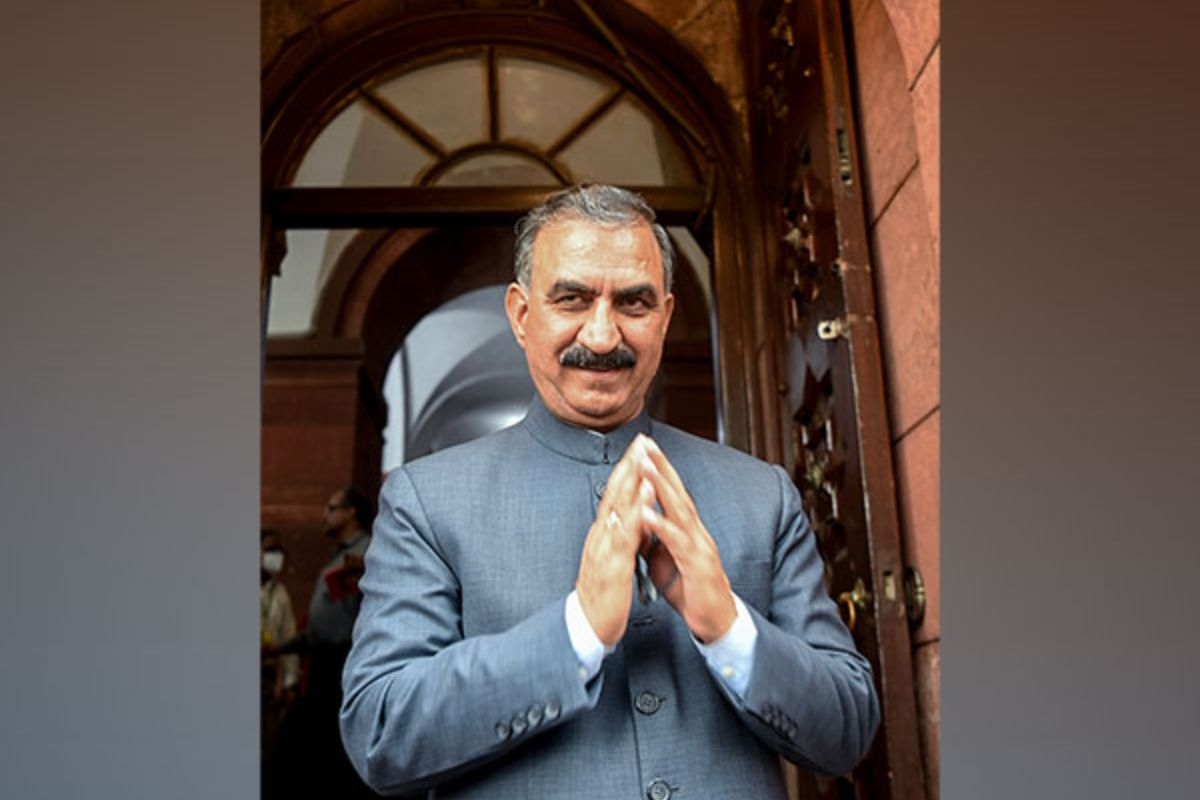

Majithia is the state's Revenue Minister and a Shiromani Akali Dal leader. He is also the brother of Harsimrat Kaur Badal, Union Cabinet Minister for Food Processing and the Chief Minister's daughter-in-law.

Other examples of official collusion with the drug trade in Punjab abound at every level and across services.

But these revelations by an ex-cop indicate the drug traffickers of Punjab are not merely a network of well-connected criminals. They involve the highest echelons of political leadership. In fact, with the authorities in their palm, they are beginning to resemble a shadow state.

Contraband: two hits on the same route

So the question worth asking is: are the two linked? Could drug trafficking be presenting opportunities for the growth of terrorism?

To answer this, first consider examples from around the world.

Back in 2003, Stephen C McCraw, Assistant Director FBI, had deposed before a Senate Judiciary Committee in Washington that drug trafficking and terrorism made up "a dangerous mix" because the former funded the latter.

The examples he cited were the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC), in Colombia, the Al-Ittihad al-Islami in Somalia, and, of course, the Al Qaeda.

It may be premature to assert terrorist operations in Punjab, or even India, are financed primarily by drug money. But it is worth keeping a worried eye on.

Borrowed leaf: global modus operandi

A 2011 US National Security Council report - titled Strategy to Combat Transnational Organized Crime - explains why this should become a key concern for India.

It says developments in technology and communications equipment have enabled transnational organised drug networks to plan, coordinate, and perpetrate their schemes with increased mobility and anonymity.

As a result, many drug trafficking organisations have developed into versatile, loose networks that "cooperate intermittently but maintain their independence".

What this implies is that funding isn't the only thing terror groups rely on traffickers for. They also use them to move weapons, ammunition and, often, the terrorists themselves.

In Punjab, it is evident that such networks have been available for a while. Both from across the border with Pakistan and throughout the state.

Both sets of drug routes have been forged primarily by the trade in Af-Pak heroin. This isn't consumed too much in the state itself because it is too expensive. But it transits through the state and forms the backbone of Punjab's drug trade because of the money it makes traffickers, even in transit.

Most importantly, it makes its way into the state through land and water routes from Pakistan.

Drugs and guns: the dual trade?

Four years ago, this writer had written a story for Tehelka magazine on methamphetamine labs in India. A source had then asserted that Jagdish Singh Bhola funded political campaigns and not only traded in methamphetamine but in Af-Pak heroin - sold at Rs 1 crore per kilo.

Bhola, of course, is now in jail on charges of running a synthetic drug empire and has confessed to funding political campaigns. This indicates the authenticity of the report about the scope of his trade.

But his role, and the possible collusion of governmental figures in Af-Pak heroin trafficking, is yet to be investigated in as holistic a manner.

Now, consider the following figures:

According to a 2015 UN Drugs and Crime report, India ranks fourth - after Pakistan, Tajikistan and Turkey - in the number of times a country has been mentioned as a 'transit point' for heroin in major individual seizures between 2005 and 2014.

According to the 2013 Annual Report of the NCB, Af-Pak heroin comprised 40 to 50% of Indian seizures between 2006 to 2012.

The same report says 737 out of 1,221 kilos - or over 60% - of heroin seized by the NCB in India in 2013, was seized in Punjab.

Finally, according to the Directorate of Revenue Intelligence (DRI) annual report for 2014-15, 94.17 kilos out of 94.33 kilos of heroin seized in India in 2014-15, or over 99%, was seized in Punjab.

All of it is suspected to have been from across the Punjab Indo-Pak border.

The Punjab problem: playing ostrich

In contrast, neither the NCB nor the DRI annual reports show any heroin seized from Rajasthan or Gujarat, though both states also border Pakistan. There are also no reports of seizures from Jammu and Kashmir.

"What these seizures indicate," said an IB official, off the record, "is that the Punjab border is 'technically porous'."

A few hours after the Gurdaspur terror strike, Chief Minister Parkash Singh Badal told the ANI that the terrorists had come from across the border and that "militancy is a national problem, not a state problem".

But the 1993 Bombay blasts - also very much in the news currently - explain why Punjab's heroin trade could well be linked with the 'national problem' of terrorism.

An NCB report says 737 out of 1,221 kilos - or over 60% - of heroin seized in India in 2013 was in Punjab

The question at the centre of that terror strike too was: How did the RDX get into the country? It got in by convincing authorities to willfully look the other way as they were told what was being smuggled was harmless silver.

The attitude towards Af-Pak heroin in Punjab is almost exactly the same. The authorities' approach to the problem is that since most of it transits out of the state and the country anyway, what's the harm in both them and traffickers making a lot of money on the side?

The fact that the same routes, and even consignments, may be used to smuggle in weapons of terror and terrorists doesn't seem to be much of a consideration.

The state's responsibility

The second point that needs to be driven home is that cross-border smuggling of Af-Pak heroin is not just a national problem.

Badal's Shiromani Akali Dal has been trying to pass the buck recently and blame only the Border Security Force for the scale of the heroin trade in Punjab.

His claim has been helped by the fact that BSF troopers have been arrested for drug smuggling in 2013, 2014 and 2015.

But some basic truths seem to be evading the Badals and the Shiromani Akali Dal.

One, no one would smuggle drugs into Punjab at the current magnitude if it were not possible to transport them further into the state and beyond. Clearly, the Punjab police and state authorities have been unable to prevent this over the years.

Two, there seems to be no political will to crack down on the nexus between the traffickers and cops and politicians. When a cabinet rank minister, accused of colluding with one of the state's biggest drug rings, is not even asked to step down, it is doubtful that collusion lower down the ranks will be curbed.

Punjab's colossal levels of drug addiction - and its harrowing impact on the youth - should have been reason enough for a crackdown.

But now the writing on the wall is even clearer: the Punjab government will have to crack down on the Af-Pak heroin trade if it wants to prevent future terror attacks in the country.

And Badal will have to acknowledge that both terrorism and the drug trade are not just national problems; they also lie in the hands of the state.

First published: 2 August 2015, 12:40 IST

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)