At IIMC 20 contractual Dalit safai karamcharis lose jobs

NOTE: The headline of this piece was changed on 18 October.

Indian Institute of Mass Communication (IIMC) in Delhi has laid off more than 20 Dalit contractual workers. Those asked to not come in for work post 30 September includes a woman worker who was allegedly raped last year by an 'influential' IIMC clerk and her husband.

The safai karamcharis (sanitation workers) were fired without any prior notice and most of them had been working there for several years. They were told that the new contractor, brought on board on 1 October, had his own workers and they were no longer needed.

These workers and other sources allege that this mass removal was a ploy to get rid of the alleged-rape survivor and her husband (both safai karamcharis at IIMC), so that the rape accused (one Sagar Rana) could be brought back to the Delhi campus of the Institute.

Also read:Dalit worker alleges rape by IIMC clerk on campus

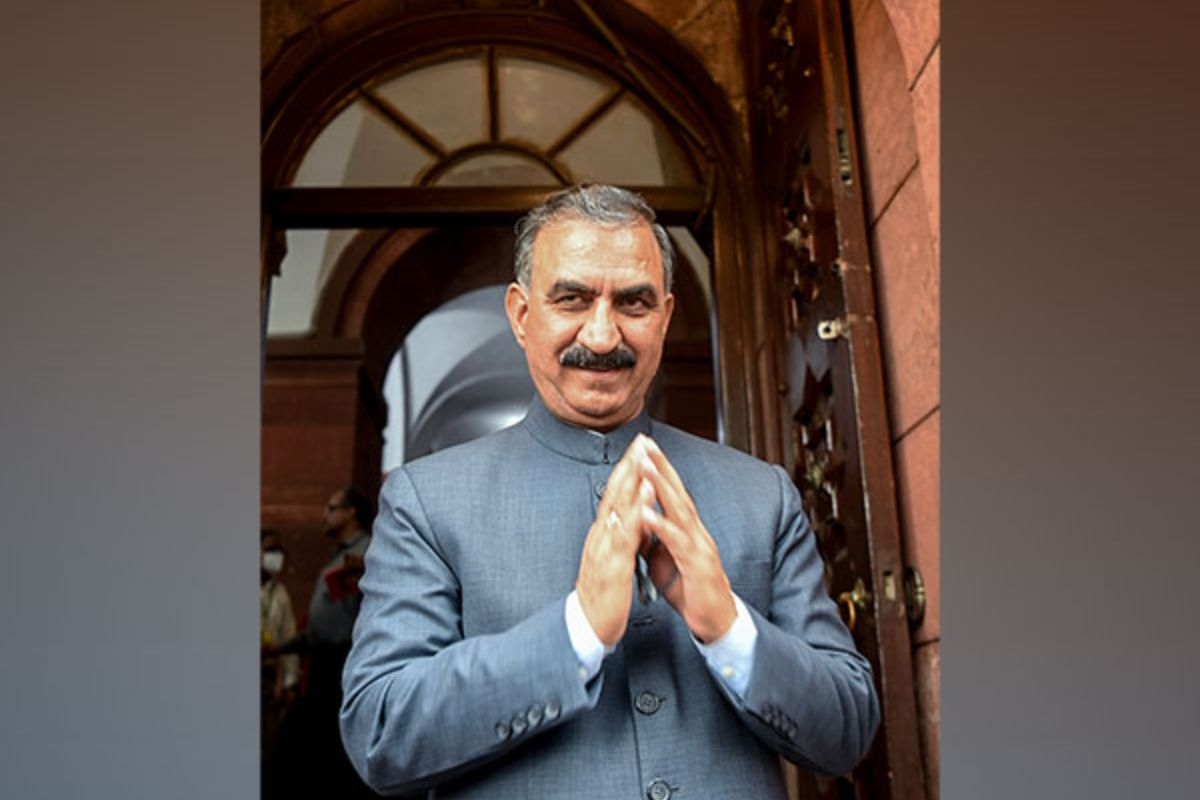

IIMC Director KG Suresh denied the allegation that the workers had been removed to facilitate Rana's return. He said the safai karamcharis were not employees of IIMC, and it was completely the new contractor's decision to remove them.

"We have done everything transparently. We have taken due action against Rana. And we need to renew the contract every two years, which had been delayed this time. We give the contract to the lowest tenderer, and it is the contractor's job to get workers. The last contractor company did not have enough workers of their own, so they chose to retain these workers. This new contractor company has their own workers," said Suresh.

Rana, a Lower-Division-Clerk at the institute, was transferred to IIMC Jammu in July this year, following court orders in the case ruling that the complainant and the accused not be present on the same work premises.

However, Rana is said to exercise some clout because his father is the official driver of the secretary in the Union Ministry of Information and Broadcasting (I&B), under which the IIMC is an autonomous body.

A cover-up?

The institute administration, including Suresh, attributed the loss of jobs to a "routine" change of the private contractor. But the workers refuted this by pointing out that contractors had been changed a couple of times over the years but no worker had lost his or her job.

In fact, private contractors were roped in as middlemen only in 2010. Before that, IIMC used to directly employ sanitation staff on a contractual basis, and many of the workers have been at the institute since those days.

Since 2010 up to September this year, the private contractor has been changed twice, but the workers had remained while being transferred from one contractor to the other, owing to an understanding between the IIMC administration and the contractors.

On 30 September, however, they were simply told by an IIMC clerk to not show up for work anymore from the next day.

The allegations

The workers Catch spoke to said that a clerk from the IIMC office and some other staff members had categorically told them that they were being removed because of the rape case, and because the accused wanted to return to Delhi.

Since the institute could not sack just the rape survivor and her husband Ramesh, the easiest way to remove them was to remove all workers under the pretext of contract change. In fact, the last contractor, Bedi & Bedi, still has a month left before the contract term gets over at the end of October. But Bedi & Bedi's contract was terminated before time and the new contractor, SNG, took over from 1 October.

Shakuntala Rani, a 44-year-old widow with three children, had been working at IIMC for eight years. She said an office clerk had told her that they were being removed because of the alleged-rape survivor and her husband Ramesh and that the change of contractor was just an excuse.

"We were shocked after we were told we were not required anymore. When we enquired, the office told us it was because of the new contractor, who had his own workers. When we asked the contractor, we were told that we had been removed on the orders of the IIMC office. Then we went back to the office, and a clerk told us that it was because of the rape case," said Shakuntala.

"We were asked to deposit our papers with the old contractor (Bedi & Bedi), and were told we'd be called if any work came up. I even visited their office last week. But we haven't heard from them so far."

Kavita, a 35-year-old widow with two sons, had been working at IIMC for 12 years. "For a few days before our last day there (30 September), we would see crowds of men and women gathered outside the gate. They seemed to have come for work. We thought maybe some of them would be hired but we did not expect that we would lose our jobs," Kavita said.

"Around 25 sanitation and housekeeping workers were thrown out initially, but a few days later four workers were called back. The administration simply told us not to come anymore. I'd been working at IIMC for 12 years and my wife for almost eight years. There are other workers who'd been here for fifteen years. The least they could have done was to give us a notice period," said Ramesh, 38, the alleged-rape survivor's husband.

Ramesh said the four workers who had been called back were all upper-caste men and employed at a slightly higher positions than the safai karamcharis.

The workers said they had tried meeting higher officials, including director KG Suresh who took charge on 31 March this year, but they had not been allowed to meet them.

Ramesh said he and his wife did manage to meet Suresh once. "We complained that we had been removed in this unfair way. He assured us he would look into the matter, but nothing has happened so far."

The workers said some administration members had unofficially told them that they would likely be hired again, and this was just to get rid of the rape survivor and Ramesh.

An employee said the lower-level administration had successfully kept the workers from uniting or protesting against the move by promising them jobs again in the future. The workers also pointed out that the security guards on campus, who were under the same old contractor, had not been removed despite the new contractor coming in.

A matter of law

As per the provisions of the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013, a workplace cannot terminate the services of the woman complainant under any circumstances until the final verdict is delivered by the court.

When asked about this, Suresh said those rules did not apply in this case, as the rape survivor/complainant was a contract worker under a private contractor. He said IIMC paid the contractor who then paid the workers. The survivor and other safai karamcharis were basically outsourced employees, he said.

So according to contract labour laws, IIMC is only the principal employer and does not count as the complainant's workplace. Therefore, it could technically be easy for IIMC to wash its hands off the case.

According to a study by the VV Giri National Labour Institute, an autonomous body under the Labour Ministry, around 32% of all workers in the public sector are employed through contractors.

Government intervention?

An employee at IIMC Delhi said that the institution remains "autonomous only on paper" and has been reduced to a bureaucratic set-up by the ministry.

"The I&B Ministry treats IIMC as its extended arm and has been trying to control everything. They have often sidestepped rules. It is no big deal that someone like Rana, who has connections in the ministry thanks to his father, could manage this move so smoothly. And of course, there is a caste angle here," the employee said.

"These workers are Dalits and they are contractual labourers, which puts them among the least privileged and the most vulnerable of the lot. Then there's the fact that Rana is a Rajput, and the ministry is filled with Rajputs. So it would be all the easier for Rana to get favours."

What lead to all this

Last October, Ramesh's wife filed a police case alleging that she had been raped repeatedly by Rana. She alleged that Rana had first raped and filmed her on 15 August at his house where he had called her on the pretext of shopping for grocery for his grandmother.

He had allegedly threatened to put up the video of her being raped by him online if she complained. She said Rana later again raped her twice at his official quarters on the IIMC Delhi campus, and he had even tried to carve his name on her wrist with a knife.

She also claimed that she had been intimidated into changing her statement from rape to molestation. In the months after the case was filed, she her husband said they had been regularly harassed by Rana's aides within the IIMC administration as well as by his father to withdraw the case.

After the FIR was registered, Rana was taken into custody and locked up in Tihar Jail from 18 to 22 October. He was then released on bail and suspended, and later transferred to the Dhenkenal.

What happened next

After the case was filed, the IIMC's Internal Complaints Committee (ICC) undertook an investigation and sent a report to the administration. Noting Rana's transfer to Dehenkenal at the time, the report also recommended that he be asked to vacate his official residence on campus, which was also allotted to him out of turn, sources said.

However, Rana never actually moved to Dhenkenal, the transfer order was revoked and he continued to be seen on the Delhi campus.

In February this year, the ICC met again after the woman complained that Rana was still on campus, and again asked for him to be removed. A police charge sheet was filed only this February.

Towards the end of July, Rana was finally transferred again to Jammu, where he joined duty in August. But he continues to retain his quarters on the Delhi campus, where his grandmother lives. Rana's family already owns a house in Delhi.

Sources said Rana had been sent to Jammu so that he could continue to keep his residence on the Delhi campus because, according to government rules, Jammu & Kashmir is classified as a "troubled" region, and a government employee transferred to a "troubled" region can retain his quarters at the headquarters.

As of now, Ramesh says the couple has no idea about the status of the case. "We have not been called by the police. We are poor and have no idea what is happening. We cannot afford a lawyer. And now we have even lost our livelihoods," said Ramesh.

Edited by Jhinuk Sen

First published: 15 October 2016, 22:48 IST

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)