This monsoon, a book on 2013 Uttarakhand floods reminds: no one is safe

The warning

- The met department forecasts that Uttarakhand is likely to see \'heavy to very heavy rains\' on 16 and 17 July

- The state is still reeling from the floods and cloudburst that ripped apart the Mandakini valley in 2013

The account

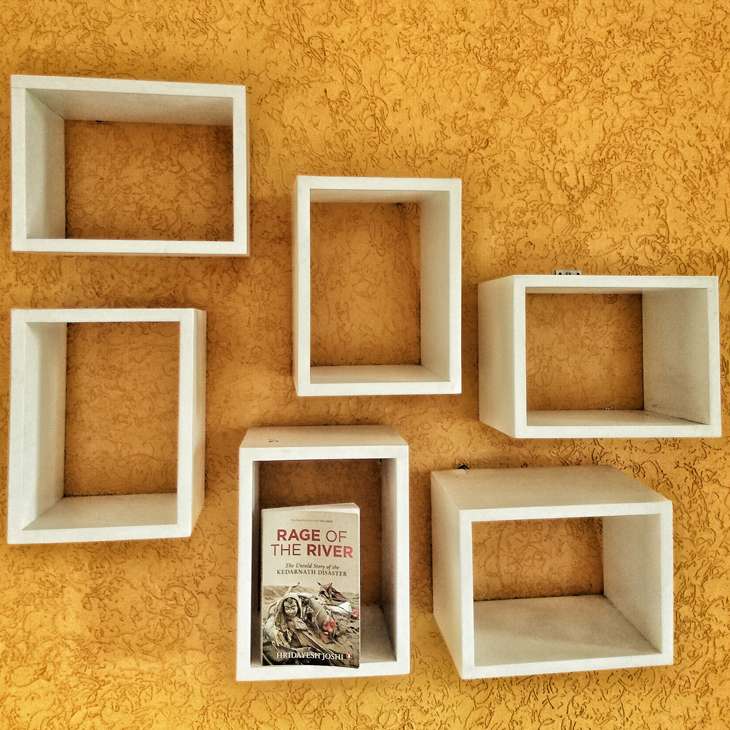

- Hridayesh Joshi\'s book Rage of the River is a bone-chilling account of the 2013 disaster

- It carries eyewitness accounts that expose the state government\'s apathy and ineptitude

The met department has issued a weather warning for Uttarakhand. It forecasts that in the hill state, there will "very likely" be "heavy to very heavy" rains on 16 and 17 July.

Even in 2013, there were warnings. But they remained just warnings. The government was later found to have done too little, too late after the disaster struck.

The Uttarakhand flash flood in June 2013 claimed between 5,000 and 15,000 lives, depending on whether you choose to believe government records or eyewitnesses.

The disaster, now known as one of India's worst recorded, and the state administration's failures, are the subject matter of a new book.

Disaster management left to the Dev

Hridayesh Joshi's Rage of the River: the Untold Story of the Kedarnath Disaster is a compelling account of not just the cloudburst and the subsequent floods, but how the state has wilfully driven itself into an endless spiral of natural disasters.

Between 15-17 June 2013, the Mandakini valley experienced unprecedented rainfall, ending with a deadly cloudburst. Although the impact was felt across the valley, the most symbolic impact was at its highest point, Kedarnath.

Kedarnath is one of the holiest Shaivite Hindu shrines, and is part of the four dhams in Uttarakhand. These are such a matter of pride to the state that the government insists it is 'Dev Bhoomi' or the Land of Gods. Dev Bhoomi's economy depends on pilgrimage, such as the one to Kedarnath, and tourists to its Himalayan ranges.

Unfortunately, disaster management was left to the Dev too.

As then-Chief Minister Vijay Bahuguna, who was subsequently ousted for doing nothing much besides planning an official-cum-personal trip to Switzerland, told CNN-IBN: "It is true we do not meet the norms of disaster management. It is also true that there is lack of personnel. We need to pull up our socks."

Maybe that's why, when the flood first struck, despite several reports from the ground, government officials took pains to be in denial, hoping that the waters would subside soon enough to prevent any embarrassment.

But Joshi, an award-winning journalist with NDTV, would have none of it. Some of his friends in the state had told him that things weren't as good as the politicians openly proclaimed.

So, along with colleague Siddharth Pande, Joshi set out on an impossible road journey through the flooded hills with just one goal: nail the government's lies with eyewitness accounts of the disaster.

Chilling accounts

In the book, which, for a large part, is a dark travelogue of the Mandakini valley, Joshi records death, destruction and bone-chilling anecdotes from eyewitnesses.

For example, on 16 June, a day before the infamous cloudburst, there was a heavy downpour, quite disastrous in its own right. Its intensity was later overshadowed by the bigger cloudburst the next day.

But an eyewitness account from the book reveals the horrors from the night before. A hotel owner in Kedarnath recounts to Joshi that as the waters rose:

"I called up my brother and my mother, and told them about the calamity in Kedarnath. I felt like it was the very last phone call of my life and I was sure I would never meet them again in this lifetime. It was a very long night. The horror of death was all around us, and each and every one was desperately waiting for daybreak... To keep myself occupied, I tried to make some tea, but this did not reduce my anxiety. We all had tea and biscuits, and then waited in the jam-packed rooms like hunted animals condemned to die. Most of us didn't sleep a wink that night, and the crack of dawn saw all our faces light up with relief. We all thought the worst was over, but no one knew that death was getting ready for one more visit."

Forget the met department and its forecasts, such a flood should have been enough for the state government to get its act together. But it did not even stop the pilgrims who were travelling towards Kedarnath. They, too, fell prey to Death's next visit, which was of course, the cloudburst on 17 June.

The government knew it all

As Joshi records, the government knew about it from the beginning.

The sub-divisional magistrate in charge of the Kedarnath region was at the temple on the 17th when the waters began rising. He climbed the giant Nandi idol and had to hang by the temple bell till the waters receded.

A pilot is quoted saying that he personally informed the principal secretary of the state's aviation department about the disaster on the 17th.

Even state minister Harak Singh Rawat had made an aerial tour, clicking photos on his iPhone. But as Joshi writes: "Despite a minister being aware of the extent of damage caused, the state government was trying to cover up the tragedy."

Delayed rescue

In the absence of government-led evacuation and rescue, private helicopter pilots worked overtime rescuing stranded pilgrims, airdropping packets of puri-sabzi cooked by villagers. Air Force helicopters were not available until four days after the disaster.

The largest choppers, ALH and MI-17, began properly rescuing survivors only on 20 June. Even then, they kept providing food and blankets when medical assistance was needed by the thousands injured and suffering from altitude-sickness.

When the National Disaster Response Force finally turned up, Joshi writes how it was full of new recruits - on contract and poorly equipped. They had "no proper clothes" and "none of them had received training with regard to such massive rescue operations".

There are at least 26 instances in the 200-page book that describe how the government messed up. But there are also an equalnumber of heartwarming stories about locals who rescued, helped, cooked and cared, despite all odds.

The book is engagingly written and offers a glimpse not just into the disaster, but also Joshi's journey reporting it. He is frank about the moments he felt greedy for information, but let go of scoops in the interest of rescue operations... and the moments when he felt emotionally overwhelmed interviewing survivors who had lost everything, including their families.

The subject matter of the book, which was originally published in Hindi, more than makes up for the translation work, which is not something to write home about. Also, the book could have been better organised, either by chronology or geography, and a full map of the Mandakini valley would have been useful in better picturing the sequence of events.

A history of disasters

The last section of the book is the most surprising. Once he's done describing the disaster, Joshi embarks on a history of people's movements in Uttarakhand. He links pre-independence forest rights movements, the Chipko Andolan, and the Tehri Dam agitation to show how the state's people have always demanded an ecologically-sound approach to development.

The connection with the Kedarnath tragedy isn't obvious at first.

Joshi implicitly points out that the impact of the agitations has diminished with time. The Tehri Dam stands tall today, as do many others (the book has an exhaustive list). There are currently 99 hydropower dams operating in Uttarakhand, and this is just the beginning. The fragile hills have been blasted to make ever-widening roads. Hotels have come up on terrace farms' loose soil. And in the face of all this, public opposition has been dwindling.

The government, of course, hasn't learnt its lessons. Although disaster management has improved, it is has miles to go, as evidenced by the situation in Uttarakhand in each monsoon season since 2013. This year, 30 people have already died in the first month of the monsoon.

The helpless situation, and a plea for change, appear to have inspired the book, as well as its original Hindi title, which is an angry question to God: Tum Chup Kyon Rahe Kedar? (Why did you remain quiet, Kedar?)

Title: Rage of the River: The Untold Story of the Kedarnath Disaster

Author: Hridayesh Joshi

Translated from the Hindi by Vandana R. Singh

Publisher: Penguin Books India, 2016

Title: Tum Chup Kyon Rahe Kedar (Hindi)

Author: Hridayesh Joshi

Publisher: Alekh Prakashan, 2014

Edited by Shreyas Sharma

More in Catch

Book review: While India holidays on its beaches, Goa Eats Dust

Hot Feminist is a book no one should read. Especially feminists

Sex Object: a book that reminds you that you never stop being just that

First published: 15 July 2016, 18:49 IST

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)

_in_Assams_Dibrugarh_(Photo_257977_1600x1200.jpg)