There are catastrophic declines in global forest covers, why aren't we paying attention?

The early 1990s were a heady time for environmentalism. In 1992, the United Nations hosted the first environmental summit in Rio de Janeiro.

The Earth Summit resulted not just in the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development - a document that progressives still call progressive - but also set the stage for the Convention on Biological Diversity (that made biodiversity a household name) and the Framework Convention on Climate Change (that gave us the annual climate change summits, the Kyoto Protocol and last year's Paris Agreement).

Yet, all of that amounted to so little.

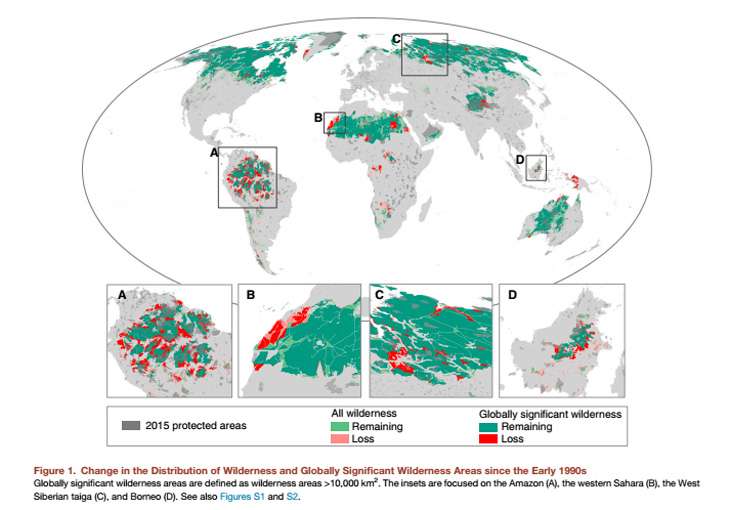

Exactly how little, a new study has shown. Since the 1990s, wilderness areas in the world have shrunk by 10%. That's 3.3 million square kilometres, which is a little more than the size of India.

The study's title is unusually alarmist to be published by a peer-reviewed publication.Catastrophic Declines in Wilderness Areas Undermine Global Environment Targets, published in the latest Current Biology, was submitted by a team of eight scientists from Australia and the US.

They found that the largest losses were in the Amazon rainforest, which has lost 30% of its wilderness, while central Africa has lost 14%.

The study expects that at the current rate, there will be no wilderness area left in the world by the end of his century.

Defining things

What makes the study more alarming is the tight definition of "wilderness". It is not just any forest. The scientists have defined it as "biologically and ecologically largely intact landscapes that are mostly free of human disturbance."

This included areas where indigenous peoples live but excludes those where major clearing for agriculture or infrastructure has taken place. The scientists also excluded Antarctica and "rock and ice" and lake regions.

Going by the definition, the study most likely excludes tree plantations, which often show up as forests in satellite images but are nothing like the forests we know of or expect to find.

And by this rule, the Amazon rainforest has lost 500,000 sq km of wilderness.

Mapping it out

Using mapping techniques, the scientists observed changes from the 1990s, when the first such studies were done, through the next study in 2002, and then recent satellite images.

They also measured changes in so-called "globally significant wilderness blocks", which have at least 10,000 sq km of wilderness.

The study found that over 80% of the wilderness is covered by such blocks.

However, of the 350 such blocks noted in the 1990s, 37 have since fallen below the 10,000 sq km threshold.

"A total of 27 ecoregions (environmentally and ecologically distinct geographic units at the global scale) have lost all of their remaining globally significant wilderness areas since the early 1990s" the study notes.

In its recommendations, the study emphasises on the importance of having large forest tracts undisturbed by major human activities. These include wildlife corridors.

"The continued loss of wilderness areas is a globally significant problem with largely irreversible outcomes for both humans and nature: if these trends continue, there could be no globally significant wilderness areas left in less than a century," the study says.

Edited by Jhinuk Sen

Also read: A good green sign: Here is all you need to know about the increased forest cover in India

Also read: 2,000 sq km of forest cover dead in Monaro, Australia. Here's why you need to worry

Also read: Maharashtra's green cover is thinning. Planting 2 crore trees isn't enough

First published: 13 September 2016, 8:24 IST

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)