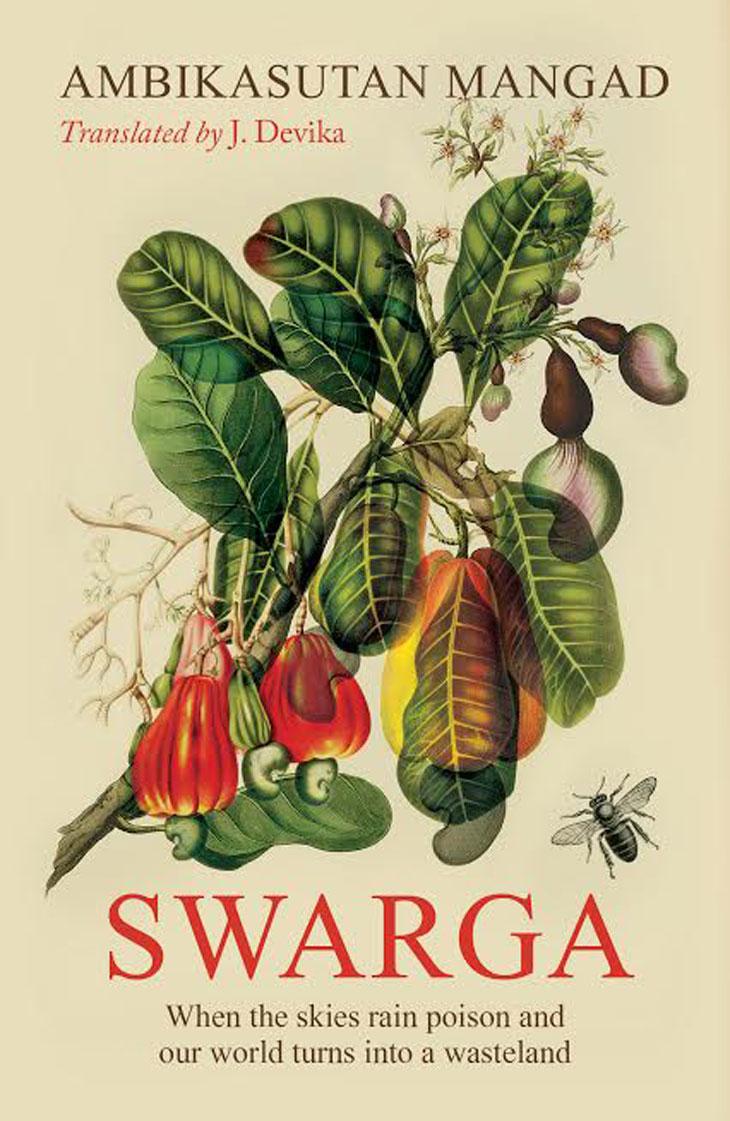

Swarga: A Posthuman Tale marks a people’s struggle against endosulfan-spraying

It is the India of the 1970s, Green Revolution is on its mind.

The government sets its eyes on Kasaragod district of Kerala with extensive cashew plantations, and decides to rid it of “tea-mosquitoes”. In its pursuit to make the area cash-rich, it sprays the deadly pesticide endolsulfan on the plantations year after year, killing the region's biodiversity and crippling its human population.

The result of this brutal war on tea mosquitoes is a seven-year-old child who looks no more than a three-month-old infant. This “baby monkey” can't laugh or cry, its body is full of sores, its hair grey, its lip cut, and when it does produce a sound – it is of someone writhing in agony.

After taking care of it for seven years, its parents have killed themselves. The doctors or the vaids have no cure for its disease. The villagers believe that the curse of the Jadadhari Bhoota has engulfed it. And them.

The child finds a reluctant home and parents in Deviyani and Neelakantan, who had shut out the human world to spend the rest of their lives anonymously in the deep jungles as “Man” and “Woman” - in what they believe is “Swarga”.

They wake up to what's happening to humans when the child comes to them, the child for whose sake they reluctantly reconnect with the world. The world that treated them unkindly, the world that left the Woman with just one breast. Man and Woman have to make peace with that world, for the sake of the child. For the sake of humanity.

The child opens their eyes to the misery around them, to the poison that is hanging in the air, laced with water and seeped into the soil, the poison that is killing all forms - except tea mosquitoes whose existence on the cashew plantations is as mythical as the Jaladhari Bhoot in the mythical hills where the book is set.

Heaven or Hell

“This was no Swarga – heaven – but hell – Naraka. The land must have yielded gold before endosulfan’s entry. The soil was so rich, so well endowed with water sources. Maybe that’s why it was named heaven,” a villager tells the protagonist.

But now this land is Naraka – hell – where a “brown powder” has been sprayed over a period of 25 years from helicopters. That powder has affected the population in a radius of 4 km leading to an increase in incidence of cancer, epilepsy, mental aberrations, low intelligence, deformed limbs and skin diseases.

“...It is a brown powder. If it falls on your body, that part becomes swollen and reddish. If it falls on an open wound, the person will become unconscious. It is like DDT – an organochloride pesticide... they sell it under some fifty retail names.”

There is enough data to show that “compared with the venom that human beings manufacture, how harmless snake poison is” - but nobody cares.

“Th er’ ’re fifty mental patients i’ the small numbe’ o’ ’ouses just aroun’ ’ere. Lots o’ abortion, cancer. My personal opinion is tha’ some terrible poison ha’ sprea’ all o’er the soil and wate’ ’ere. Jus’ can’ make ou’ wha’ tha’ is. The little boy you saw befor’, Abhilash? He wa’ jus’ like a monkey when he wa’ small, now somewha’ human in form... wha’ is that forc’ that’s reversing evolution? I ’ave no clue’,” says the 200-year-old vaid who has stopped by to check on the monkey-child.

The journey turns out to be not as easy as Man would have thought when he decided to slip into shirts once again to spearhead ESPAC - Endosulfan Spray Protest Action Committee.

The powers-that-be go for the kill.

The story moves from myth to history to myth again – because it is difficult to take on Naraka. In this case, vile politicians, because they would rather care about making money off the government plantations than worry about a human population being erased.

Activist-Author

Ambikasutan Mangad was actively engaged in the anti-endosulfan struggle in North Kerala. He decided to write the book when he visited a village to study the extent of the poisoning between 1976 and 2001 on plantations owned by the Plantation Corporation of Kerala.

On that visit he met a child – just like the monkey-child Pareekshit in “Swarga”. That memory found its way into the book when it was published in Malayalam as “Enmakaje” in 2009.

Drawing on the myth of Kerala’s beloved king Bali, reminiscent of tales from the Panchatantra and the Mahabharata, Mangad tells the heart-breaking story of a people’s struggle against endosulfan-spraying.

“Aswatthama was cursed with a hellish life because he had committed an unspeakable sin. But this child who suffers like him, with sores all over, oozing pus, what sin did he commit to suffer this living death? Who is sending Brahmastras against so many children in Enmakaje?”

Mangad's book was translated as part of an initiative of the Thunchath Ezhuthachan Malayalam University – a “project to unlock the creative power of Malayalam, enhance its reach, and enrich world literature, through translation”. The Malayalam title, currently in its 14th edition, is studied as a textbook in several universities.

(Swarga by Ambikasutan Mangad, translated by J Devika is available in bookstores and on www.juggernaut.in)

First published: 15 April 2017, 14:35 IST

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)