Crime, terror & Karachi: the killer prose of a cop-turned-writer

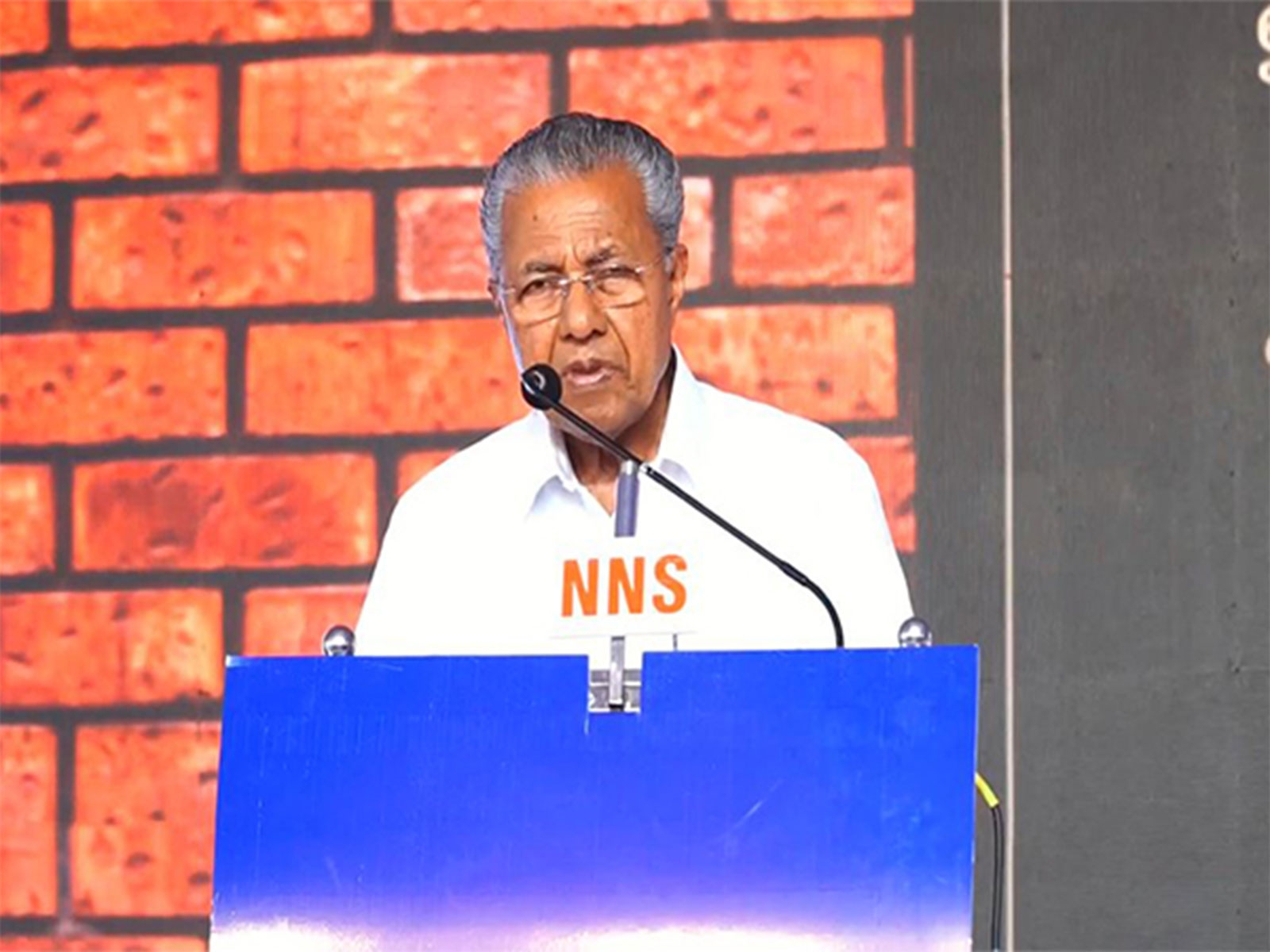

Omar Shahid Hamid knows the dark underbelly of Karachi. Intimately. For 13 years, he served in the city's police, eventually rising to head the CID in Karachi.

His decision to become a cop was no accident: while he was still in his teens, his father, a senior civil servant in Pakistan, was assassinated by the MQM. As a cop he became the target of many terrorist organisations himself.

Less obvious - but no less welcome - was his decision to become a writer. His first book - that he finally took a sabbatical to write four years ago - propelled him firmly onto the Pakistani literary scene in 2014.

Called The Prisoner, it was a gritty, unpretentious page-turner that is, in fact, a telling account of his own life - one that felt real enough to win him a place on the longlist for the 2015 DSC Prize for South Asian Literature. It offered a rare glimpse into Hamid's complex battles with gangsters and hypocritical jihadis, seedy politicians, powerful intelligence agencies and corruption.

Now, Hamid returns with his second novel - The Spinner's Tale - that tackles an equally complex subject, the radicalisation of youth and the horrors of terror. Set in Karachi, Kashmir and Afghanistan, the novel follows three school friends - Ausi, Eddy and Sana - with Ausi transforming into Sheikh Ahmed Uzair Sufi, a top Jihadi militant in Pakistan.

Catch sat down for an interview with the author, which is followed by a short excerpt from his new book:

You write fiction. How much reality is mixed in?

Both my books draw from real-life experiences, whether they occurred to me or my colleagues, or from recent headlines. So the books aren't necessarily fact, but they have a real connection to actual events.

In The Prisoner, you drew from events such as the Daniel Pearl kidnapping and Mir Murtaza Bhutto's assassination. What events inspired The Spinner's Tale?

When I was working in the Crime Investigation Department (CID), the question that always vexed me was how seemingly 'normal' people could commit the most evil acts upon being convinced that they have motive. For instance, the story of Omar Saeed Sheikh, the man convicted for the murder of Daniel Pearl, always fascinated me.

At the CID, I always kept note of the reasons militants gave for why they became radicalised, and The Spinner's Tale is an attempt to explain that journey.

The Prisoner trades on insider knowledge, but also pays tribute to unsung heroes. How did your former colleagues from the Karachi police force receive it?

I have received congratulations and praise from all of the police officers who have read The Prisoner so far.

You spent 12 years in the police. What learnings came from that experience?

I learned many things and I would not have been able to do any of the things I have subsequently done without the invaluable experience of being in the police. But to pick a couple of points: policemen are the barometers of any society because they see every cross section - usually at its worst. So if you want to know what's going on in a country, or region, your best bet is probably to talk to the policemen of that place.

The Spinner's Tale is about young men who go down different paths. This narrative has been explored in films like Khuda Kay Liye and books like The Reluctant Fundamentalist. How is yours different?

Once people read it, I think they will understand that The Spinner's Tale, while exploring themes similar to earlier works like The Reluctant Fundamentalist and others, is actually a very different book. At its heart, it is a detective story, a thriller - something to set your heart racing.

There are some wonderful descriptions of Karachi in The Prisoner. Is it a strong character in the new book as well?

Karachi is still the setting for parts of this book, but the book also meanders through other parts of the world. In that sense, if you are looking for a true Karachi-based sequel to The Prisoner, that would be my next book, The Party Worker, which I am currently writing. It looks at the politics of the city.

Sabeen Mahmud was shot dead in Karachi when she organised an event to help amplify unheard voices from Balochistan. What strategic value does Karachi hold for extremists?

Like any urban environment of its size, Karachi represents opportunity for various criminal elements, who often disguise themselves in the garb of either religious movements, or political parties.

But the basic reality of the city is that the violence is bred by the clash of disparate criminal groups fighting for the shrinking resources of the city, and being facilitated by the deterioration of the state apparatus and its inability to counter these forces.

In The Prisoner, you dove deep into Karachi's police force. Does The Spinner's Tale have a similar focus on an institutional body?

I don't know if The Spinner's Tale has a singular focus like The Prisoner. I suppose if there is one, it would be the process of radicalisation that leads a person into being a jihadi.

You worked closely with senior officer Chaudhry Aslam to manage the CID's extremist cell. Parts of The Prisoner were inspired by his work. After his death last year at the hands of the Taliban, some people have wondered who will take up his mantle.

Both my books have often been based on my work with Aslam, who was a very dear friend. Aslam's legacy will always be that he showed people a way to fight against the mafias that threaten to engulf Karachi.

Your father, former KESC chief Malik Shahid Hamid, was murdered in a targeted killing. Is that a closed chapter?

On 12 May, the death sentence given 16 years ago by the courts to the man convicted for the murder - Saulat Mirza, a militant belonging to the MQM - was carried out.

Is The Spinner's Tale the second of many books?

Writing was something I literally stumbled into. But once I had stumbled across it, I found that it has now become central to my life.

----

The Spinner's Tale

An excerpt

The Present: 21 April 2011

The desert can be a scary place at night. Darkness descends very quickly upon the barren landscape. The night brings with it a bone-tingling chill. But it is the silence that is most unnerving. The slightest noise is amplified tenfold as it echoes across the vast empty spaces. The wailing of a lonely jackal sounds menacing. The sparse vegetation casts sinister shadows and the whistling wind tosses up dancing balls of dust that look ethereal in the moonlight. In a place like this, the mind starts playing tricks on the senses. Every shape, sound and shadow brings with it an associated sense of dread.

This was especially true of the small group of policemen who huddled together over a campfire in this particularly desolate corner of the Nara Desert. Their little camp was set in the middle of two single-storey buildings in the middle of nowhere. The closest signs of civilization were across the Indian border, two kilometres away. The buildings themselves were dilapidated, with doors, windows and all other fixtures having long since been removed. Only one room, in the larger of the two buildings, had a shiny new set of iron bars in the window. The road that led up to the encampment was little better than a dirt track. At the entrance of the compound was an old board, hanging from its hinges now, that proclaimed this place to be the Forestry Department's School of Animal Husbandry.

The sun had only set an hour ago, but already the desert was enveloped in darkness. The sole light came from the fire around which the men sat. It was the month of Ramadan, the month of fasting, and the policemen had had to content themselves with breaking their day long fast with some stale naan bread and soggy pakoras. But they were fortified by strong tea, brewed in a steel kettle over the open flame of the campfire. It was the first time in the day they had really taken stock of their surroundings. The morning had been spent in ceaseless activity, setting up the place and in resisting the pangs of hunger that the first week of Ramadan inevitably brought.

One of the men, the tallest of the lot, a constable called Peeral, noisily slurped his tea from the cracked china cup. 'This is not a good place to be in. I have heard stories about this place . it's haunted.'

The others hushed up, looking around nervously for any sign of the supernatural. The sudden sound of creaking metal startled all of them, making two of the men spill their tea. The stoutest of the lot, a rotund man by the name of Juman, was the only one who hadn't moved at the sound. He laughed. 'You bloody idiots. It's only the back door of the pickup. You know it always creaks, we've been meaning to get it repaired for some time. All of you know this, yet you let this village simpleton scare you. Tell me something, which chutiya ghost is going to haunt an animal husbandry school?'

The others laughed uneasily. Peeral frowned. 'It's wrong to abuse them. We don't want any passing spirits to take offence.'

'Listen Peeral, the only spirit passing this place would be the ghost of a horny buffalo who died while mounting a cow. Any self-respecting ghost wouldn't be caught dead here.'

The mood lightened after Juman's comment and the laughter was much more relaxed. Only Peeral remained doubtful.

'Okay, Juman, granted it's an animal husbandry school. But that doesn't mean there were never any people here. What if one of the researchers had died here and his spirit is still wandering about?'

'And how, pray tell, would the researcher have died? Was he struck by lightning while he was masturbating a buffalo? Yes, I'm sure you're right, there's a spirit walking around here right now with buffalo sperm on its hands.'

The men chuckled again and another of them spoke up. 'It's not the dead that I'm worried about, it's the living. Arre baba, do you even know what we're doing here? Who are we supposed to be guarding?'

'A living ghost.' Juman took a sip from his tea, allowing his words to sink in.

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](https://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)