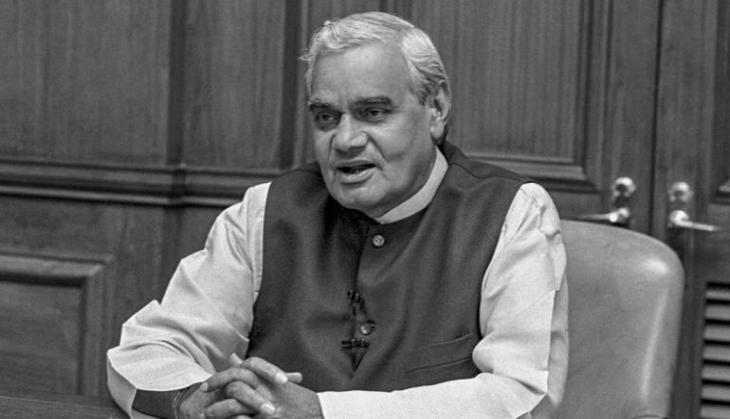

Mandir, mask and the man: Vajpayee in the reporter's eye

The following are two excerpts from Shades of Saffron -- from Vajpayee to Modi by veteran journalist Saba Naqvi on the late Atal Bihari Vajpayee, who died Thursday. The book has been published by Westland.

The Journey

(Page 16-18)

Was Vajpayee really opposed to the Ram temple movement? I believe at some level there was a genuine revulsion, perhaps even aesthetic, in the way things were panning out around the mandir–masjid. I remember following him to Surat in Gujarat during the campaign trail. One day, even as he stepped out of his car, a volunteer who appeared to be in a state of frenzy, began shouting, ‘Jai Shri Ram’ (Hail, Shri Ram). I vividly recall Vajpayee turning around and snapping rather poetically, ‘Bolte raho Jai Shri Ram; aur karo mat koi kaam!’ (Keep shouting Jai Shri Ram; do little else)! It was one of those Vajpayee moments I shall always remember.

Around the same time, Atal Bihari Vajpayee granted me an interview, which was published in India Today magazine where I then worked, as part of one of the first cover stories I wrote on the BJP. We spoke about many things, but the major thrust of the interview was that he wished to separate the BJP from RSS. ‘It is ridiculous to say that the BJP would be remote controlled by the RSS. The RSS has views of its own. The BJP has views of its own. And the BJP is adjusting to a more real situation.’

Another memory from the 1998 campaign is of the time when a reporter asked the BJP’s prime minister-designate point-blank (which seems impossible to do these days) what if his party lost the elections. Unfazed, and with a twinkle in his eyes, Vajpayee had retorted, ‘Then it will be agli bari, Atal Bihari’ (The next time over, Atal Bihari Vajpayee; the campaign slogan in 1998 was, Abki bari Atal Bihari, this time around, it’s Atal Bihari). It was this self-deprecating humour in Hindi that made the man stand out among conventional politicians.

On 4 December 1997, the then President of India, K. R. Narayanan dissolved the 11th Lok Sabha. There was a certain irony in the fact that it coincided with the BJP holding its first all-India Muslim Youth Conference at a stadium in Delhi. Vajpayee couldn’t resist cracking a joke even on that day—‘People may suggest that we have an understanding with the President to dissolve the Lok Sabha on the day we have our first Muslim conference.’

I remember being told by party cadre how they had instructions not to raise the ‘Jai Shri Ram’ slogan. Naturally, I attended the event and was quite amused to see silence on Ram, but leader after leader going up on stage and reciting Urdu couplets, showering praises on Muslim heroes, many I hadn’t even ever heard of. L. K. Advani proceeded to give examples of India’s composite culture: he spoke of Hindus visiting Sufi shrines, and Meo Muslims.* K. R. Malkani, veteran Jana Sangh leader, who at that time headed the Deendayal Research Institute, came up with two gems which I dutifully noted in my reporter’s notebook—‘Ram–Rahim ek hain, Krishna–Kaaba ek hain,’ (Ram and Rahim, as Krishna and Kaaba are one and the same), he said in the spirit of oneness. But the very next line had prompted Atalji to stare at Malkani, who said, ‘No Muslim will oppose Atalji even if he stands from Islamabad.’

However, the news point for me that day was a significant statement by L. K. Advani who appealed to Muslims to give up their claim on the Babri masjid in Ayodhya, while assuring them that he would personally negotiate with the VHP to find a settlement to the Kashi and Mathura disputes.

The Mask

In 1998, Atal Bihari Vajpayee traversed the country making meaningful speeches about swasthya, shiksha and suraksha (health, education and security). He openly admitted to being irritated by questions about the Ram temple in Ayodhya, the Uniform Civil Code, or the revival of the Hindu rashtra. Even occasional queries about Kashi and Mathura would irk him no end, and he would choose to keep silent.

However, it was also true that the building of a grand Ram temple in Ayodhya was a core issue that the BJP couldn’t afford to ignore, as it had contributed to its great electoral leap in 1991. Vajpayee therefore made a subtle change in tack and said that it was no longer necessary for a BJP government to enact a legislation to build a temple at Ayodhya. ‘We will resolve the issue through dialogue—the same way we resolved the Azadari dispute between the Shias and Sunnis of Lucknow. A law will not be needed.’

Lord Ram could never be jettisoned by the BJP. There were other voices like that of Kushabhau Thakre, who later became party president—‘Can anyone think about India without Ram?’ he once asked me, but added with utmost honesty that, ‘We can only implement our ideology if we have the strength to do so. Yeh sab hamara karyakram hai, lekin shakti nahin hai’ (All this is on our agenda but we lack the strength to pursue it).’ That was a euphemism for saying that their ideology will not be jettisoned, but only deferred for some more time.

This shall be said many times over in the book—Vajpayee was different from the run-of-the-mill RSS worker because he perceived politics as an art of the possible. It wasn’t as if he wasn’t close to the Sangh Parivar, it was rather well known that he enjoyed a great rapport with the then RSS sarsanghchalak (supreme leader or chief), Rajju Bhaiya. That said, Vajpayee also had some contempt for those in public life who did not have the ability to win elections. He was always more comfortable in the company of former Rajasthan chief minister, Bhairon Singh Shekhawat, Jaswant Singh and, later, Pramod Mahajan, all traditional politicians. One of his famous retorts to the ‘mukhauta’ controversy, hinted at his impatience towards back-room organisers such as Govind. ‘I must be enjoying the full confidence of the party or else I would never have been bestowed with the highest honour of being the prime ministerial candidate.’

Yet, among the hard-liners, Vajpayee did not come out tops. Sadhvi Rithambara, notorious for her venom-spewing remarks about Muslims during the Ram janmabhoomi movement, described him as, ‘half a Congressman’; while the then chief of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad, the late Ashok Singhal, was barely on talking terms with him.

As far as the Advani–Vajpayee relationship was concerned, it had layers of complexities. On the one hand, there was mutual respect based on long-standing friendship and association. Advani, typically like several RSS functionaries was adept at handling the nitty-gritty of organisational matters—something Vajpayee had no patience for. But once Vajpayee settled into the prime ministership, the question about who was more powerful remained unanswered. Advani because he had greater party and RSS backing? Or Vajpayee because he had greater mass appeal?

It was the clear-headed Advani who would describe what the BJP was going through as, ‘The transformation of an ideological movement to a mass-based party. That is why there are hiccups at every stage. Take the recent agonising over the party’s manifesto. While a manifesto may be so much waste paper for most political parties, every small nuance is pored over in the BJP.’

In sum, by the time of the swearing-in ceremony on 19 March 1998, the BJP had shown far greater flexibility than it was credited with having. The umbilical cord to the RSS had not been cut, yet the Vajpayee facade was instrumental in convincing several parties to go along with the BJP. Vajpayee himself said quite artfully, ‘Sometimes circumstances may have forced us to take a hard line. But the BJP has always been a moderate party.’

There’s no denying that putting the NDA together required deft work and it revealed the political intelligence of both Advani and Vajpayee. Ironically, it was during the 1998 campaign trail that Vajpayee would frequently attack the United Front (UF) coalition (that got outside support from the Congress party) for lack of ideological clarity with lines such as, ‘Kahin ka eent, kahin ka roda, Bhanumati ne kunba joda’ (A brick from here, a brick from there, that’s how Bhanumati got her flock together). The BJP had done pretty much the same, but the difference was that they would make it work.

As for the Govindacharya issue, Vajpayee would eventually deal with it with a sense of humour. There was a point when he stopped referring to Govind by his name, and would privately tell members of his inner circle how ‘Rajneeshacharya’ (reference to a godman with a large following) did this or that. Apparently, once Vajpayee genuinely forgot his name and referred to him as ‘Dronacharya’!