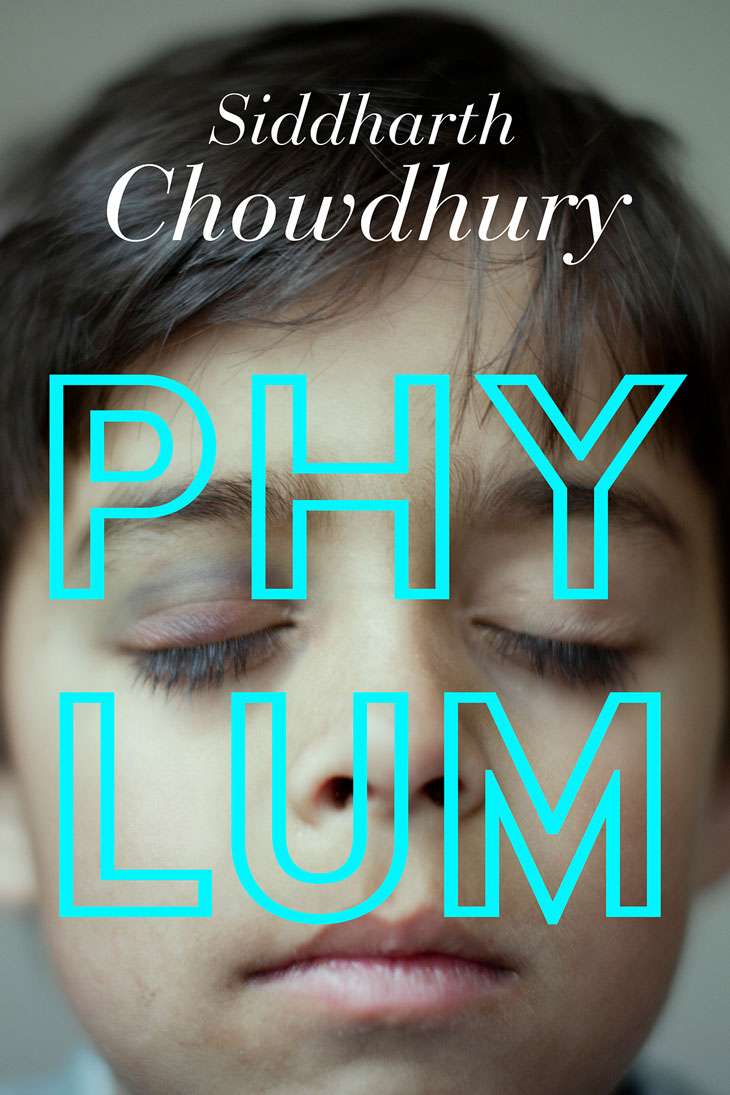

Siddharth Chowdhury's 'Phylum' is a reminder of the intolerant world we live in

Siddharth Chowdhury is a slow writer. By his own admission his output isn't much and "at the best of times it is quite frugal". But when he does write a few thousand words, it is impossible to ignore his writing.

Here's why.

Chowdhury's just published short story Phylum on the Juggernaut App is about the intolerant world we live in. A world which can lynch us over a beef rumour, a world which is policed by lathi-wielding gau sainiks, a world which, as Chowdhury says, is moving increasingly "rightwards".

A truck full of beef is found abandoned on the highway, a beef smuggler is caught by some villagers, as John Nair - the protagonist - makes his way to his farmhouse for the weekend dodging the gau rakshaks and risking his life to save those stranded on the highway.

The story will bring back ugly memories of Mohammed Akhlaq being lynched by a mob on the suspicion of eating beef in Dadri last year.

Chowdhury's Day Scholar was shortlisted for the Man Asian Literary Prize and The Patna Manual of Style for the Hindu Prize for Fiction. Chowdhury who is frugal with the spoken word too, talks to Catch about Bhasha India - a world he transports us into with Phylum -- and also Bhasha literature which he says is mediocre, just like most of Indian writing in English is.

Edited Excerpts:

LH: I love the extensive detailing in your writing. Do you always see the world as a writer?

SC: Most of the times I do see the world as a writer. I would pick out small things but there are probably many bigger things that I miss which other people probably see. I probably pick up things which are interesting to me and file them away for future reference. I think most writers do that.

LH: The details are intense, so real. You almost feel you are on that road with John Nair about to encounter truckloads of gau rakshaks...

SC: As a storyteller that's what you try to do. Like, if you are writing about Patna, someone who has never been to Patna should see Patna through your eyes. At the same time it should not alienate them. They should get immersed in the story. It's the same with Delhi or with any other place that one writes about. It should be a rough guide without being a rough guide - in a way.

LH: At the heart of the story is the beef war?

SC: Yes.

LH: Has this been playing on your mind since the Dadri lynching incident last year or even before?

SC: It has been there before also, but of course after the Mohammed Akhlaq incident I thought it is terribly bad to tell someone what to eat and what not to eat. And of course now it has become a matter of life and death, which it shouldn't be. Most Hindus don't eat beef anyway and most Muslims don't eat pork. Fine, everybody knows that and people work around that.

But if someone wants to have then what's the problem? Why make rules for others? Make it for yourself. You don't want to eat beef that's fine.

Once it becomes a matter of life and death - when you make it into an election issue, those things have been election issues from time to time before too but haven't actually carried on for so long... And now you have gau rakshaks or vigilante groups those were not there earlier. So those things are quite terrifying. It shouldn't happen in a democracy like India.

LH: Why are we suddenly becoming aware of our castes?

SC: In the last 10-15 years everyone has moved rightwards. I think the whole world has moved rightwards. People have started taking pride in their caste. You would see it more in the OBC caste - Yadavs, Gujjars or Jats. It's probably a kind of a celebration.

But I think it is better not to be proud about anything - about being a Brahmin or a Rajput or a Pathan.

LH: In Phylum the protagonist marvels at those who can tell people's castes by looking at them. Can you tell people by their castes?

SC: I could do it with 70% accuracy. I knew people in university who could do it with 90% accuracy.

You could know so much about caste, you still won't be authentic if you are not a good writer. I don't think that kind of knowledge helps my storytelling. One could not know anything about caste, yet write a very good story about India. Even though I would know more about caste than other people, I don't think that would help my story telling.

People say that in Indian writing in English they really don't know much about caste. I don't think they need to know about caste, if they get to know about people I think that's alright. This is true for any kind of writing - whether in Bangla or Hindi. I don't think it kind of adds.

Though people say Indian writing in English has moved away from caste and people who are writing it, they don't know much about caste, which is probably largely true. They do probably come from a class, they won't know much about it, could be. But if they are good, they are good. I don't think it kind of helps.

LH: There's a lot of you in the story...

SC: (laughs) Yes.

LH: Your answers in the past have varied from there's 29% to 90% of you in your stories. How much of your work is truly autobiographical?

SC: (laughs) I had to give an answer, so I said that (29%) because mathematically it would sound a little better.

I have always said that I am an autobiographical writer, but I am also a storyteller. I like to tell a story which will keep people interested, but it should be a story I strongly feel about. If you are living with a story for a year - or five or six years (laughs) - it is better you start writing something that you absolutely believe in.

LH: No offense meant, your writing is absolutely beautiful, but the pace at which you write don't you think you are lucky that there are now Apps which are publishing standalone stories?

SC: Yes and no. I usually publish a book every 5 years. I published a book last year in 2015, so probably my next book would come around 2020 and Phylum might be a part of it. Most of my work is connected in a way. I thought the Juggernaut platform would be perfect for something of this length. And I wanted to try it out. So I sent it to them and they liked it.

LH: You've been asked this before - how do you pick names for your characters? Phylum has a Rifat Pandita-Nair, there is an Osama and Saddam and there's a Twitter handle @nafratnahin...

SC: (Laughs) Well you know you work hard at it. The thing is to make it look seamless, but writing this took me over a year. I am anyway quite a slow writer. My output isn't much - even at the best of times it is quite frugal (laughs). For something like this - I wrote about six drafts and I wrote the last draft just about 20 days back.

I wrote the first draft a year ago. The Osama and Saddam thing wasn't there in the earlier drafts. It came in the 4th or the 5th draft. It suddenly struck me and I also thought there is a nice timing to it... And I did have a car cleaner whose name was Saddam. Then it struck me that before the 1970s you find very few Rahuls, or Priyankas. Even Sonia. I thought let me use this.

LH: In this story we also see the world of a rather kind publisher who risks his life to get people home safely, but he also remembers to make fun of Bhasha literature...

SC: That I thought was an interesting drift. John Nair is quite an anglicised publisher in a way. My thinking on Bhasha literature or Indian writing in English, or any other kind of literature is simply this - only 10% books in any language in each year are good, 90% are mediocre.

So I don't think literature in one language is more authentic than the other. If someone is writing in Hindi I don't think he is more authentic than someone one writing in Urdu or English.

LH: But there is this sudden celebration of Bhasha literature...

SC: I think most of Bhasha literature too is mediocre, like most of Indian writing in English is. This is what I feel. I have read a lot of Hindi literature, read a lot of literature in English, also a lot of translated writing. And 90% of it is mediocre. I think personally a translation should only be done of books which have reached a kind of a classic stage, maybe at least 10 years after publication and not everything should be translated. What happens is when you translate everything, true mediocrity of Indian literature comes forth, and that is what has happened.

LH: But you also say it is a safe game to play...

SC: Of course it is a commercial thing also. It is cheaper to buy.

LH: Are we saying that Bhasha literature is the new fad?

SC: John Nair thinks it is a safe bet. And he has burnt his fingers, he has also started doing it and that in turn brings him face to face with his 'Dalit Delight'.

LH: I wish there were more details about the 'Dalit Delight' (John Nair's secret love interest)... SC: There could be another story about her. These are all labels. At the end of the day a good book is a good book - which tells a good story in a simple way, and then you can market it any way you like. You can call it Naga Nationalist, you can call it Dalit literature, you can call it colonial literature...

LH: A lot of Bengali books are being translated into English...

SC: Yes. I have myself published translations or edited books of other publishers. But what I have felt is that many times these books are chosen just because they are kind of safe and there will be a market for maybe 600-700 copies.

LH: I like the way the "Random" girl strikes a mega book deal...

SC: (laughs) You see the Random girl has a better timing to it than the Picador girl. Everyone does it, but the Random girl has a random ring to it.

LH: Are you really a social media recluse?

SC: In a way, because I am not on Facebook or Twitter. So one can call me that. But usually because I don't have much to say at most times. I do press interviews, I am not a recluse in that way (laughs). I do a 9-5 job, I take phone calls, meet hundreds of people in a week, those are absolutely connected to my professional life.

LH: Is it true that you write your drafts in longhand?

SC: I do write in longhand and I do write with a pencil - the first 2 or 3 drafts. Sometimes my wife helps me out with the typing. I am a slow typer.

LH: When do we expect to see the next story?

SC: I don't know (laughs). This has exhausted me in a way. In some ways, this is quite a difficult story to write. There are many strands in the story. The Phylum of caste, of language, of beef-eating...

LH: Are you happy with your 9-5 publishing job?

SC: It's a living. It works for me.

LH: How often do you feel like throwing a manuscript out of the window?

SC: My job is to improve it, most of the time. If I have accepted something, I don't throw it away. I try and improve it to the best of my ability.

LH: You are happy in your world?

SC: In a way. I love publishing.

First published: 17 November 2016, 11:01 IST

_251049_300x172.jpg)

![BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH] BJP's Kapil Mishra recreates Shankar Mahadevan’s ‘Breathless’ song to highlight Delhi pollution [WATCH]](http://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/11/03/kapil-mishra_240884_300x172.png)

![Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE] Anupam Kher shares pictures of his toned body on 67th birthday [MUST SEE]](http://images.catchnews.com/upload/2022/03/07/Anupam_kher_231145_300x172.jpg)